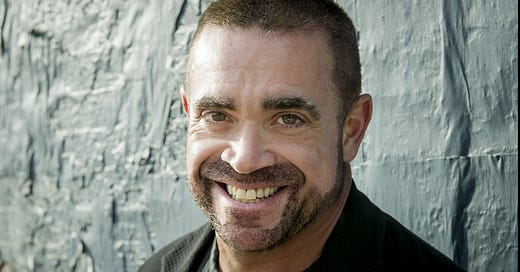

It was a real pleasure to sit down with Anthony de Mare, the visionary pianist behind Liaisons: Re-Imagining Sondheim from the Piano, a landmark commissioning project that has transformed Stephen Sondheim’s songs into bold, virtuosic solo piano works. As he prepares to release Liaisons II: All Things Bright and Beautiful—out March 14, 2025, on AVIE Records—de Mare reflects on the deeply collaborative process behind this latest collection, which expands the Liaisons repertoire to 50 pieces. Featuring re-imaginings by composers from across classical, jazz, film, and musical theatre—including Meredith Monk, Max Richter, Jon Batiste, and Stephen Hough—this new volume continues to bridge Sondheim’s legendary songwriting with contemporary composition. Our conversation begins below:

We’re speaking ahead of the second volume of your Liaisons releases, “All Things Bright and Beautiful.” Even this second phase of the overall project is years in the making. You must be so excited to finally be able to share this disc with the world. Could you talk a little bit about its gestation period?

The ECM three-disc box set of the first collection came out in 2015. By 2017, my manager at the time had suggested, “His 90th birthday is coming up in 2020. Have we thought about anything that we might want to do?” We thought it would be a great gift to him for his 90th birthday. There were also so many composers that had kept asking, “Will this extend? I’d love to be part of it.”

And so, with that impetus, we thought that expanding might be a good idea. We went back to Sondheim for his thoughts and ideas, as we always did. We always checked in with him on everything, and he liked the idea. He was humbled and grateful, and we were excited by that idea. Of course, we asked him to recommend some composers that he would like to see, and I had a list for the second collection as well. Most of his choices were theatre composers who could really play the piano—and several overlapped with the composers that we had in mind, too.

So with the new collection, we went back to a few of the original commissioners, some new commissioners, some new partner commissioners with organizations or presenting organizations, and it started to come together. Fundraising is always a mountain to climb. The first collection was 36 pieces, so I thought, what if that went up to 50? So we decided to add 14 more in this volume.

Again, we wanted a diversity of genres. We wanted diversity in compositional styles, too. When you hear each piece, in nearly all cases, you can recognize the original song—but you also recognize that composer’s style. Each piece truly is a kind of marriage. Stephen was always delighted by that fact that these composers had their print on the pieces as well as his, and he took it as a sort of honor to know that these composers, many of whom he admired himself, were so interested in his melodies and harmonies, and wanting to recreate these songs in the form of a piano work.

The pieces started coming in in 2019, and there were a whole series of concerts around the country booked from March of 2020 and onward for the rest of that year, all of which had to be canceled. Luckily, nearly all of those premieres were rescheduled within the two years that followed.

I’d love to know more about how collaborative your relationship with each composer is, and the extent to which that differs from composer to composer.

Like for the original collection, all the composers were given parameters to follow. Some of that went along with what Sondheim wanted himself, which was first and foremost to try to preserve the melodic material, and some of the harmony. One of the things he said along the way is that his musical material is sometimes condensed, as it’s expanded by lyrics and narrative. So he realized that the structure of the piece would probably change because there’s no text—except in a couple of cases. He knew that the form and structure of the songs would change.

Most everyone stuck to that. Some were direct transcriptions or arrangements, others took the word “re-imagining” to heart and really expanded on it, based on the atmosphere of the song. There was a lot of back and forth collaboratively. Composers sometimes were stumbling. They were baffled. What we heard a lot was, “The songs are already perfect.” For others, they said it was a walk in the park. They knew exactly what they wanted to do.

We asked that the pieces be anywhere from three to eight minutes long. Many of them fall within the four to six-minute category. I think in the new collection, Meredith Monk’s is almost nine. But there were a couple that were very short in the original collection as well. Some of them knew that the statement they were going to make was going to be as long as it needed to be, based on what they wanted to do and what they saw. But they were all given free rein to reimagine in the way that felt best for them.

There are a lot of stories about composers choosing songs. In the original collection, I always bring up the composer David Rakowski, who did “The Ladies Who Lunch.” It’s a song I just adore, but I thought it was so lyric and character-driven, I didn’t know how it would work as a piano piece. But that was the only song David wanted to do. He had a really strong idea of how he wanted to set it. And he captured the Bossa nova, he captured the character’s pathos, humor, sadness, bitterness, and yet he made a really beautiful piano work out of it. And others did that as well, choosing unusual songs that I didn’t think would work—like “Epiphany” in the first collection. That’s a really complicated song, and I thought, how is this ever going to become a piano piece?

In this new collection, there were several songs that I’d always wanted in the first collection that no one chose, and some I really pushed like “Not a Day Goes By.” So I was very happy when Jeff Beal, the film and television composer, chose that one to set. Another one was “Move On,” and Conrad Tao did such an amazing job with a two-piano version. The recording is with me and him, and he’s amazing. I think he’s one of the greatest living pianists right now, as well as being a composer, improviser, creator. He’s really got a musical mind like no other, and so I was very grateful to have him be part of it.

Some composers did just go along their own route, and then sent me what they came up with. Others would send me something and say, “What do you think of this? Am I on the right track?” It was different with each person, and each piece really became the voice of that composer. And I wanted that. I wanted them to truly do that with each piece.

And on this new disc, there are a couple of pieces which involve an extra dimension beyond the acoustic piano. I’m thinking of Jon Batiste’s take on “Gun Song”/“The Ballad of Booth” and Christopher Cerrone’s re-imagining of “Kiss Me.” Could you give readers a sense of what’s happening in those pieces?

Chris Cerrone had said all along that he was going to do something with electronics, because that’s a genre that he works in a lot. He also had mentioned that it would help to play on the frenetic quality that the original “Kiss Me” has, that nervous, anxious quality between Johanna and Anthony. He prepared four notes of the piano [i.e. placed objects on the piano strings to alter the sound of those notes], so that the “I have a plan” figure would stick out amidst that ostinato repetition and the atmospheric electronics that hover throughout.

In Jon Batiste’s case, he sent the piano part, and he said, “There are going to be spoken audio tracks that will be embedded over it.” Those came much later, and he marked in the score where he wanted them. I didn’t know at the time we asked Jon how much he wrote music down, because he’s an amazing improviser. He sits down at the piano and comes out with these brilliant things. And I asked him purposely, “Would you please write it down?” He said, “Sure, sure, no problem.” And of course he sent a fully notated score with the cues and everything. And he was so keen on combining those two songs from Assassins.

Which works so well with the more contemporary audio as well, doesn’t it?

Yeah, and it’s got his marvelous jazz harmonic sensibility in it. I think Sondheim was very fond of that piece. I had sent him the score. He never was able to hear the finished product. He was planning to come to the concerts we had to postpone because of the lockdown. A year and a half later, he was going to come to hear the rescheduled premiere at Merkin Hall—and that was a week before he passed away.

During the lockdown, though, I did make home recordings so he could hear some of these pieces, and sent him a lot of the scores to get his feedback. The composers were always beyond curious as to what he thought. Any suggestions that he’d make, they would immediately give over to. “The master has spoken.”

In broad terms, obviously without divulging anything private or specific to one composer, what sorts of feedback would Sondheim offer?

I’ve got the original notes here. He says, “They’re fantasias responding to the melodic lines and harmonies, and occasionally the accompaniments. But all the pieces in the collection surprise me. They take approaches that would never have occurred to me. As you might expect, each approach is startlingly different from the others, and it’s fun for me to hear which of the song elements each composer latches onto, and how far they spin from them.”

He did tell me privately which ones he really admired. He liked them all—and in the first collection, he sent an individual note to every single composer, thanking them, which was really gracious and wonderful of him. There were three premiere concerts for the original collection in New York, and for the second concert I had invited him ahead of time to come to my apartment. I wanted to play through some of the pieces to get his feedback. In one case—I won’t mention which—in the original collection, a composer had misquoted the melody, and he seemed really bothered by that. The composer was completely shocked that they had missed that, because they had been working from a memory of the song as opposed to the original score. They fixed it right away.

He was really taken with Eve Beglerian’s setting of “Happiness” from Passion. But at the very end, it sort of just stopped originally, and he said, “Couldn’t that diminuendo and sort of slow down like it’s going to fade away for the last four or five measures?” I told him I’d present that to her and see what she says. And of course, when I called her and told her, she was like, “Oh yeah, that’s a great idea.” So there were things like that.

He was very subtle about any changes. He really respected what each composer did, because he knew it was their voice. He didn’t want to interfere with that, unless there was a mistake. In the new collection, there was a misquote, and he was very annoyed by that. He wrote a note to me. He even said, “How did you not see that?” And he said something so interesting about the mistake, because this composer had written an octave leap instead of a seventh. “The seventh asks the question,” he said. “The octave is too definitive.”

There were so many moments where I was so enlightened by what he said in terms of insights into his work, insights that either I didn’t know or I missed, or something that all of a sudden made more sense.

And I was so pleased that your own piece on this disc is based on “All Things Bright and Beautiful,” cut from Follies but still a prominent part of its Prologue. Was that always a number you saw as ripe for re-imagining?

Yeah, there’s a great story for that. When we did the second concert in New York for the first collection, a few of us were backstage in the green room with Sondheim. My husband Tom at the time struck up a conversation with him, and off the cuff, he said, “You know one of the songs that I’ve always loved of yours that I wish had been kept in the show? ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful.’” And Sondheim said, “Yeah. You know, I always liked that song myself. I really liked it.”

So when it came time to choose, I think because Sondheim had said he always liked it, it made sense to choose it. I also didn’t believe anyone else would ever choose it. And listening to the opening of Follies, that whole orchestration is so lush and so amazing. I wanted to capture that on the piano. And in playing lot of these re-imaginings, you can’t help sometimes but hear the influences on Sondheim from other composers, so I decided I wanted to pay tribute to that too. There’s a touch of Ravel, there’s a touch of Satie, there’s a touch of Copland, there’s a touch of Rachmaninoff. I even put Richard Rodgers in there, and for some reason at the end, though this is not an influence on Sondheim, it ended up going in the direction of John Adams.

I didn't realize “All Things Bright and Beautiful” would be the title of the album until just last year. We decided we wanted a really positive title for it. I thought it would work perfectly.

It’s a title that resonates beautifully. And congratulations, this whole project is such a fantastic achievement. How brilliant to have all 50 pieces out in the world at last, and what a gift you’ve given us all.

Liaisons II: All Things Bright and Beautiful – Re-Imagining Sondheim from the Piano is released on 14th March, 2025. For more information and to pre-order/order the album, visit the AVIE Records website by clicking here.

You know, a video of De Mare playing one of the new pieces would make a fine addition to the Hub...