A Conversation with Barry Joseph

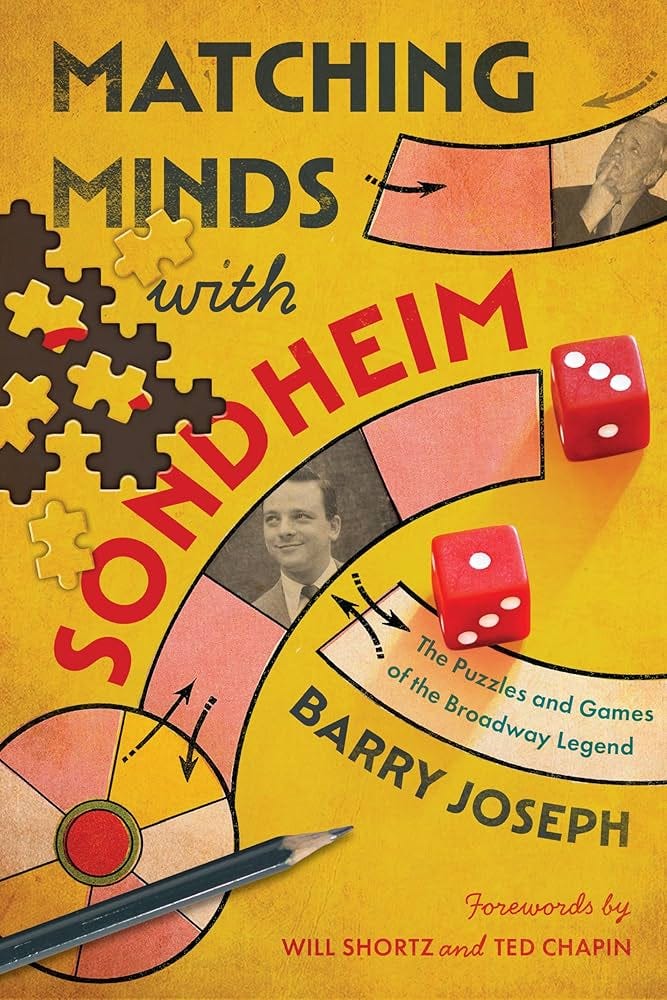

on Matching Minds with Sondheim: The Puzzles and Games of the Broadway Legend

Barry Joseph is the author of Matching Minds with Sondheim: The Puzzles and Games of the Broadway Legend, a unique exploration of Stephen Sondheim’s lifelong passion for designing intricate puzzles and games: from crossword puzzles and treasure hunts to parlor and board games. Drawing on his own background as a national leader in games-based learning and games for social impact, and on the firsthand accounts of those who played and designed games with Sondheim, Barry’s book is a treasure trove of insight into Sondheim’s deep engagement with games, the people with whom he played them, and what they reveal about his “puzzler’s mind.” Our conversation begins below:

If you find The Sondheim Hub valuable, consider a one-off $5 donation to support our work!

Barry, it’s great to talk to you. Matching Minds with Sondheim is a book three years in the making. What was the original impulse behind it—and when did you know it had to be more than just an idea?

I don’t think I was fully aware of it at the time, but it was my way to mourn the loss of an artist whose work had touched me deeply throughout my life—and to get to know him better. I wanted to understand not only his work, but the remarkable way that Stephen Sondheim made sense of the world and the people around him.

He passed away in November 2021, and my birthday is just two days away from his, so I was quite aware that the following March marked the first birthday he wasn’t here to celebrate and be celebrated. His birthdays were always major events, especially here in New York City, and online too. That year, my partner bought me three different Sondheim books for my birthday—some old, some new. The late-90s Meryle Secrest biography, Sondheim and the Reinvention of the American Musical by Robert McLaughlin, and finally Putting It Together, the oral history James Lapine compiled of Sunday in the Park with George.

Reading the biography fascinated and delighted me when it touched on his interest in puzzles and games, but that topic barely existed in the book. There’s nothing related to puzzles or games in the index. Still, it told me more about his life. Then I read McLaughlin’s book, which takes a specific lens and applies it to Sondheim—similar to Richard Schoch’s approach of asking how Sondheim’s shows teach us about our lives, then applying that lens to the work. I thought, what other lenses might exist?

And then, what really blew my mind and got me started was reading, at the beginning of Putting It Together, about the period between the critical disaster of Merrily We Roll Along and his rediscovery of a voice through his partnership with Lapine for Sunday. During that time, he was so upset with the state of Broadway that he was considering leaving. And when James Lapine asked him where he’d go, he said: video game design. Lapine didn’t just quote him saying “game design,” but specifically “video game design.” This was the early 1980s. I was growing up playing home video games—Kaboom, Sea Battle—and I couldn’t imagine the Stephen Sondheim I knew, who wrote the lyrics for West Side Story, who created such incredible music, actually wishing he were designing video games.

And then he meets Lapine, and they make Sunday, and that became his path. But I thought—what if he had followed that other path? Where did the idea even come from? Where would it have gone? So combining those three things—understanding someone from a biography, using a particular lens, and that lens being game design—came together from reading those three books.

And so the question then is: why did that resonate for me? It resonated because I’ve had a lifelong love of Sondheim. I’m from an area close to New York City, so I grew up going to Broadway shows. I clipped all my Playbills from the time I was a kid. I really respect the power of musical theatre.

At the same time, I’m a game designer and producer. I’ve worked in the field of social impact games and educational games for over two and a half decades. So I could appreciate that when Sondheim was growing up, into his twenties and thirties, when he was thinking about a career, puzzle and game design might have been something that engaged his mind, something he enjoyed—but it wasn’t widely respected as a profession. It didn’t have the same opportunities for self-expression and professional growth.

Today, things are very different. Whether you’re talking about the explosion of Eurogames like Catan in the U.S., the board game renaissance, or the fact that for decades now, video games have out-earned box office receipts and several other major mediums combined, we’re in a very different world. And knowing the power and potential of Sondheim’s personal passions, I wanted to figure out where he explored them. That was the impetus.

What really got me was how deep that rabbit hole went—and how early it started for him. As a teenager, he was designing board games he wanted to publish, word games he submitted to the New York Times—unsuccessfully in both cases—all the way to the final years of his life, in his late eighties, when he was still designing treasure hunts for hundreds of people at major cultural institutions. And in between: board game designs, parlor games, treasure hunts, innovative word puzzles, and a passion for physical puzzles like jigsaws, puzzle boxes, and finally escape rooms. I needed to get to the bottom of this.

And to do that, I had to talk to the people who were there—in the room where it happened, so to speak. The people who designed the games and puzzles with him, who he trained to make their own, who played them, who he made them for. That meant speaking with people within six to eighteen months after he passed. It meant asking people to open their hearts and their memory boxes, diving back twenty, thirty, forty, even sixty years, and trusting me to be the custodian of relationships built not around creating stage art, but playing: playing with their friend, and sharing that friendship.

I wonder to what extent the process of writing this book feels bisected: before the Doyle auction, and after. You were there on that day. Can you give readers a sense of how that experience contributed to the book?

There’s so much to say about the Doyle auction. First, I’ll say it’s the epilogue of the book—which tells you the role it played. It came at just the right time to sum everything up. I live in New York City. I was able to take the day off and spend the full ten and a half hours at the auction, from before it started until after it ended. I was one of maybe half a dozen people still there at the very end.

I spent the day at the auction and the few days prior at the reception and expo. I met so many people I’d only met remotely for the book: interviewees, fans of my Instagram account I didn’t know but who knew me, friends I now have because of the project. Everybody was there. It felt like a giant party we were all privately having. This included people I never imagined I’d meet: friends of Sondheim, collaborators, Broadway creatives. I don’t want to name-drop, but it was surreal.

That was the social part. On the research side, I had spent two years meticulously social-engineering and strategizing: how do I even find out what exists, and how do I access it? By creating a Facebook account, an Instagram account. I was holding up a lantern: “If you know something, contact me.” I’ve used that method for other books. It’s fun. You build a community where there wasn’t one. Then the community comes to you, and the project exists because of that community.

There’s a fellow up in Rochester whose thing is The Last of Sheila. He collects everything imaginable. That included, at one point, a very rare photo from an old eBay auction of a promotional jigsaw puzzle package for the movie. Until the Doyle auction, all we had was a picture of the box and the recipient’s address. No one knew what was inside. Someone else found a publicity letter sent with it—using all this hyperbolic language about how amazing the movie was. But we didn’t know what was actually in the box.

Then I walked into the Doyle auction exhibit—which lets you handle everything during that period—and saw not just one of the boxes, but all of them. I think there were eight. I opened them up, dumped them out, pieced them together, and discovered what was on each one.

A few months earlier, Sondheim’s homes in New York and Connecticut had sold. In a photo of the Connecticut house, you could see a whole wall of jigsaw puzzles—and those boxes were there. This was that collection. It had been saved since the early ’70s, and now we could discover the contents. Whether or not you care about jigsaw puzzles, that’s just one example of dozens of items that were previously inaccessible. I worked so hard just to learn that they existed—and suddenly, I was walking into a museum of them. It felt like walking into a museum of my book.

Some of it was personally satisfying—touching what I’d only seen in photos. But some of it was actual information. The two most exciting discoveries were that Sondheim had designed two board games—one in the early ’50s, one in the late ’50s. Everyone I spoke to presumed they were gone. Even Sondheim said in interviews they’d been discarded. And there they were on the auction site. The boards, the pieces, the rules—everything.

So first, we found out they existed. That alone was thrilling. Second, we could finally see what they were. But then, third, they were pulled from the website. Within days, they disappeared. So something happened. Maybe they weren’t meant to be listed, or someone requested they be taken down. But it meant there was this very tiny window where we got a special insight into his game development. If that had happened even a year later, none of it would have made it into the book.

I’m fascinated by how you approached writing about the games, especially for readers who haven’t seen or played them. It reminds me of the challenge of writing about music for people who aren’t necessarily musicians. How do you capture something so complex or intricate without it reading like an instruction manual? Or is the key to focus on the stories around the games?

I wanted to write a book about Stephen Sondheim for people who don’t know very much about Stephen Sondheim. I also wanted to write a book for people who don’t care that much about games or puzzles. So essentially, I wrote everything in the book without presuming any prior knowledge or existing passion. My job was to both inform and excite readers, and to help them understand why this is so interesting.

For the game designers and puzzle crafters reading, I do go into detail. I talk about how Sondheim built his game designs using popular board game mechanics from the time, or how he innovated crossword design by adapting British cryptic crosswords for an American audience. But I still try to keep the reader engaged, so they can follow that arc as a story—a kind of historical development—and understand why it’s meaningful.

And when it comes to Sondheim as a person, I’m not really talking about the shows. I’m talking about how his mind worked: how he used game design to create moments of clarity for the people who experienced them, and moments of connection between those people and, often, Sondheim himself.

It reads like a story. You’re following the anecdotes of someone who had been hearing for years about the games Sondheim used to host in the sixties. And now it’s the nineties, and they want to play them too. Why hasn’t he done one recently? Why won’t he throw another game night? And then they finally convince him to do it—so what happens? You’re there with them in the moment.

I was able to speak with, I think, the only person left alive who actually participated in his 1969 Halloween treasure hunt—the one he designed with Anthony Perkins. They told me what it was like to be there: when that limo rolled up, when they got thrown in it with a bunch of other musical theatre celebrities, being driven all over the city in a frantic rush to solve puzzles on maps. This was the first time Sondheim had ever done anything like it. So in the book, you’re right there with them, solving puzzles in the backseat.

The book is designed to highlight the ways games and puzzles can be forms of art—forms of self-expression—and to ask what it means that Sondheim used them in that way. How can we look at the games he created and understand him better through them? Why was he driven to create these moments of connection? And what do those impulses tell us about his personality and his motivations?

And you’ve also launched a podcast to sit alongside the book. Can you give people a sense of who they might hear from, and what those conversations are like?

I’m a terrible note-taker. When I interview people, I always ask if I can record the conversation so I can use transcription tools afterwards. I promised everyone that those recordings would never be used for anything else without their explicit permission. Then, when I was finalizing interviews for the book, I said: “If you’re open to it—and there’s absolutely no expectation—I’d love to use the audio in a podcast series.” That was a test, to see how many people would say yes.

And I ended up with about thirty hours of interviews that I was cleared to use. Once I saw I had that much, I got really excited, because there are so many different ways to slice and dice it. The interviews include people who had a direct connection with Stephen Sondheim: people who played his games, collaborated on his shows, went to his parties, helped him throw them. That’s a small, limited group. But what I’ve been able to do is take audio clips from those interviews and then bring in a second circle of guests: people with expertise in crossword puzzles, people with expertise in Sondheim’s music. I have them listen to those clips with me and respond to them from their own perspective. That’s been such an exciting proposition.

So what we’re offering is a chance for listeners to hear the actual voices they’re reading about in the book—and then go a layer deeper, as a broader conversation unfolds with others. Sometimes we’ll do an episode focused on a specific section of the book: let’s talk about treasure hunts, or board games, or escape rooms. Other times, we’ll explore a theme—like, how do games and puzzles operate in Sondheim’s music, both in the songs and in the structure of the shows? And still other episodes feature interviews with other authors who’ve written books about Sondheim, where we compare and contrast approaches and talk about how the sausage is made.

For more information, and to preorder Matching Minds with Sondheim, click this button:

If you find The Sondheim Hub valuable, consider a one-off $5 donation to support our work!

The sort of post we Sondheads live for!