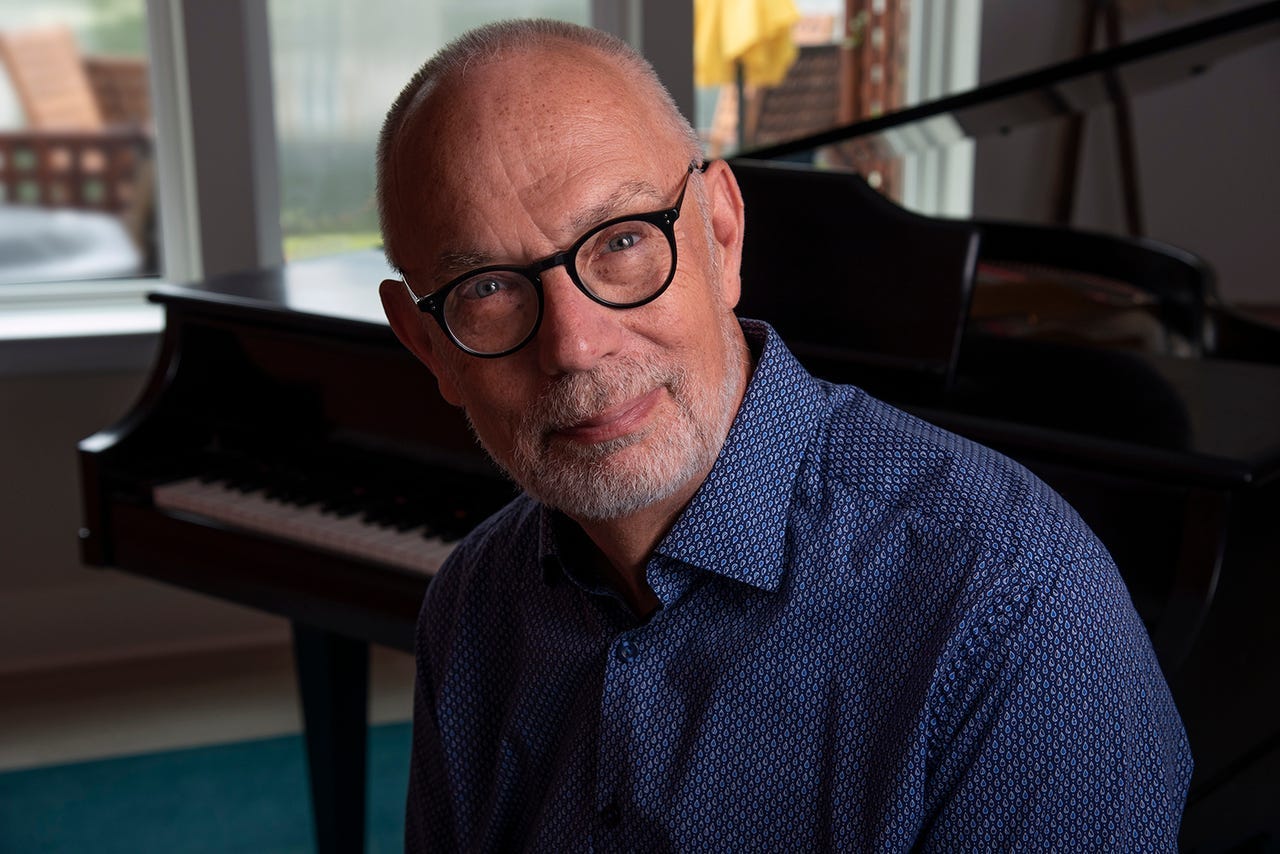

Anyone familiar with Assassins will have noticed the credit: “Based on an idea by Charles Gilbert, Jr.” This week, it is an honor to welcome Mr. Gilbert to The Sondheim Hub. In our conversation, we explore the serendipitous moment in a Pittsburgh library that sparked the show, his decision to entrust that original concept to Sondheim and Weidman, and his perspective on the show’s enduring relevance in an age of political violence. Our conversation begins below:

Thank you for reading! Upgrade to paid to support our work & receive our Sondheim Supplements: exclusive essays, weekly crosswords, extended interviews, & more.

It’s such a pleasure to meet you. I’d love to start in 1977, when you’re at the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh and you stumble across these biographical sketches about various assassins. You saw dramatic potential there straight away. Can you pinpoint that moment of inspiration?

It’s so serendipitous when I look back on it, because it really was a case of walking through the stacks of the library and having this random encounter. Nowadays, maybe we wander through the internet and encounter things, but to be on that particular floor and by that particular shelf really was a lucky thing.

At that time in my life, in my early 20s, I was eager to make something. I’d finished grad school, I’d had a little bit of experience with creating work there, and I thought, okay, now it’s time to dig in and make something. And I had in mind the idea of collages, or bricolage, of finding bits and pieces that you could assemble, that would create meaning as you brought them together.

And I remember in particular with these assassin stories that there were passages written in their own words. There was courtroom testimony, or jailhouse diaries, or papers they had left behind afterwards. I remember Charles Guiteau’s “I Am Going to the Lordy” poem that he wrote on the day before his execution. There were a few things that were like that, and that seemed to be the really promising stuff to me: those things that were verbatim, where these individuals were kind of speaking across the years. And I know that for Sondheim and Weidman, that was one of the things about the material that was most intriguing to them, too.

Fast forward to 1988, and you receive a letter from Sondheim, in which he says that he’s been haunted by your idea ever since you submitted your Assassins script to the Stuart Ostrow Musical Theater Lab. He asks to take the idea on himself. What was going through your mind as you weighed that decision?

It felt very tricky at the time. I wanted to make the right decision because I had the sense that this was a singular occurrence, that it was so improbable, and so I wanted to do it right. I enlisted the help of a lawyer, who seemed at the time to be a very expensive New York arts lawyer that I found through a recommendation, who was a big help to me in guiding me through what I might expect in a situation like this.

Looking back at it now, it was the best thing that could have happened for that idea. Steve and John were in a place to take that idea and do something with it that would never have been available to me. Even though their Assassins is a musical I didn’t write, the show has carried an idea of mine farther than anything else I’ve ever worked on. And, to be honest, it has made me more money than anything I’ve ever worked on. So again, that’s a sort of random but amazing thing when I think about the good fortune of that.

But at the time, I did think, what should I do about this? And I thought in my youthful enthusiasm that maybe there was an idea to put my oar in as a collaborator. That felt like a very nervy thing. I told Meryle Secrest I thought it was a cheeky thing to do, to say, “Well, we should do this together, Steve.” I mean, imagine summoning up the nerve to say that! But that wasn’t to be.

They were, though, very cordial about hearing from me at a couple of points along the way in the development of the show. But at the time, I thought, well, gee, I hope this is the right thing to have done. I got the best advice I could, advice that was of a kind I’d never had to seek before, and happily, it all worked out. But yeah, at the time, it was like, do I give away my baby so that it will have a better life than I could ever provide it? That sounds sort of melodramatic, but I guess that was the train of thought that I was grappling with then.

Given how highly you thought of Pacific Overtures, did the fact that John Weidman became Sondheim’s collaborator for Assassins weigh at all in your enthusiasm for their show?

Sure. I had a lot of regard for John’s work on Pacific Overtures, and I knew that John was very much my age, my generation, whereas Steve was really more my father’s generation. So at the time, I felt like when I was in the room with both of them, sometimes it felt like I was connecting a little bit more with John than with Steve.

But looking back on that decision, it was very smart. The work that Weidman created in his libretto for Assassins was brilliant: the way he threaded the needle and solved that problem of tying together all these disparate individuals. That was the puzzle that I had been wrestling with, too, is how do you take all of these things that are connected because of the circumstance of them all being presidential assassins, but where a lot of it is also kind of scattered? How do you tie all of that together, and how do you build towards a climax? How do you create a theatre event that engages you on a rising rollercoaster ride of emotion and expectation? And I thought that John’s solution to that was so brilliant.

So, I guess I hoped for the best at the time, but even if it had been someone unknown to me, I probably would have said yes to the project. In some ways, I’d actually moved on from Assassins. I’d moved on to my next project. I thought that I’d gone about as far as I could go with it, and I was actually in the midst of writing something else, something very small. My next project was a show for four actors and a piano, because I was aware that Assassins is a project that required some substantial theatrical resources. So strategically, I was thinking small at that point. And Assassins was on the shelf.

You mentioned wrestling with the puzzle of making Assassins cohere. I’m fascinated by your original conception, which featured a disaffected Oswald-like figure threading through the narrative—although Oswald himself did not feature.

Yes, Oswald was not in my original script. As I worked on the show, I was very interested in Oswald, and certainly there’s the most research and historical information available on him. But I thought, well, could I use that story of an individual, disaffected loner getting caught up in a web of conspiracy as the through-line, the spine, for this show? And could I then attach all these other historical figures to this character in a kind of theatrical way?

That was what I was working on. I mean, that was one of several things that I was trying, all at the same time. I was a young writer, and I was kind of throwing everything I could think of at this idea. Looking back on it, I would probably say that my Assassins was an ambitious hot mess.

And so to see somebody like John Weidman come to that material and sort it out was remarkable. I gather, from hearing Sondheim tell the story, that John just kind of went away and did that on his own. John was able to put those pieces together. I was never quite able to sort out the relationship between the collage aspect of the play, which was random and experimental, and then this narrative, which was almost like a police procedural or something. I could never quite thread the needle between those two things.

How present were you during the show’s development at Playwrights Horizons?Were you able to be in the room much as Assassins came together?

I probably would have hung out there a lot if circumstances had permitted, but I was not in New York. I live in Philadelphia, and I had a job and family here, and so there was a lot that kept me out of New York.

The first time I saw what they were going to do with the piece was at the reading that they did at Playwrights Horizons. They did an invited reading in 1989, with Nathan Lane as Sam Byck. I still have the program. It was a pretty amazing cast and an amazing group of people in the room for that. That was the first time I actually saw Assassins, and I thought, wow, okay, this is going to be an exciting ride.

I did finagle an invitation to the recording session for the original cast album of Assassins. I went into the studio itself, and I sat in a corner, watching much of the recording of that cast album. I remember that so clearly, and some other occasions over the years, too. But had circumstances permitted, I definitely would have been around more—just to be in the room where it happens.

It’s funny you use that phrase, “the room where it happens”—because Assassins has proved so hugely influential on the next generation of musicals, in both content and form. How do you see its legacy today?

Well, I don’t think I’m alone in being really intrigued with history and historicizing as the material for making musicals. Whether it’s Pacific Overtures, or Hamilton, or Suffs, there are lots of examples of musicals that have seized on something historical and taken a kind of radical or revisionist or freewheeling approach to that. That seems to be a pretty standard strategy for creating art and creating musicals.

I’m currently an artistic director for an organization that is supporting writers of new musicals, and so I hear a lot of pitches for ideas for musicals. Many times, there’s some historical figure that’s at the center of the pitch. So I don’t know if there’s anything new about it. But I do think that part of what’s fascinating about Assassins is that it’s pan-historical, in that it deals with characters from the 19th and the 20th centuries, characters with a lot of different backgrounds, different educations, different ways of thinking and speaking and seeing. I think that’s one of the things that does set Assassins apart.

As we’re speaking, political violence once again dominates the American national conversation. Do you think that the pan-historicism you mention is key to why Assassins continues to speak to us so potently?

I do think that that’s something that gives the show continued relevance. As you’re speaking, I’m thinking about the introduction to the song “Another National Anthem,” where there’s a kind of musical vamp, and where, one by one, the assassins say why they did it. They each have a one-sentence reason, like, “I did it because she wouldn’t return my phone calls.” “I did it to avenge the South.” They’ve been distilled down into these very brief sound bites, and we hear them in a kind of overlapping way, so that out of the variety of their motivations, something begins to emerge, which is: I want to make them listen. Someone has to listen, right?

And when you speak about political violence in the present moment, that’s the thing that I think about. People are desperate to make themselves heard and make themselves felt at a moment when we feel so powerless in the face of enormous forces that we’re unable to control. So yes, I think that is certainly something that gives the show an enduring meaning and relevance.

I know that you were generally so delighted by Assassins at Playwrights Horizons, but that you did have a small quibble with the foregrounding of the assassins themselves at the expense of bystanders. This is prior to “Something Just Broke,” of course—but could you talk a little about that perceived imbalance?

I’m not sure what on earth gave me the temerity to give a note to the authors, but I did it. As I thought about it, I was noticing that these bystanders, the characters who are not the assassins, kind of disappeared from the stage after the first half of the play. I thought that that was interesting, because for so much of the first half of Assassins, we see that interplay between the assassins themselves and other characters in their worlds. There are the bystanders in “How I Saved Roosevelt,” there’s Emma Goldman with Czolgosz, and so on.

I remember talking to a rabbi about the play. I’d been invited as a guest for a Hebrew school where they were doing a production of Assassins, and we talked about whether the play kind of lost its moral compass, its sense of humanity, the compass of human values at that point. And so it was interesting to me to think, well, now we’ve gone so far into the point of view of the assassins that we lose sight of this other thing, which is that they’re really just a small splinter of society. It was an interesting thing to try to articulate—really, just an idea.

I composed a letter about it. Sondheim and Weidman and I had a conversation about that. It was just fascinating to me that they saw it too, and that they found that argument persuasive, and eventually responded in that way, with “Something Just Broke.” Because of the tone of it, and where it falls in the story, I think that’s an important song. It’s an important correcting influence in what might otherwise be a very skewed sort of universe.

Assassins is extremely popular with students and with community theatre groups. What advice would you have for someone about to embark on a production of the show?

Well, I have had the chance to talk to different colleges, either in person or on Zoom, over the years about Assassins. The advice that I give is do your homework, because the piece is so rooted in history—but then you have to let your imagination work too. Often, the thing I come back to in these talks is the fact that when I conceived of this idea, I was just barely done with being an undergraduate. The ideas that you have as a young artist can sometimes have real value, lasting value, and you have to be open to that.

When we’re young, sometimes we’re a little bit grandiose about what we think we’re going to accomplish, but other times, I think we’re quite realistic. And so I’d say this: it’s really important to honor your imagination and your creative impulses. When you follow those, you will be surprised. It won’t necessarily lead you to the place where I ended up with Assassins, but it will certainly be an interesting ride and an interesting adventure.

Finally, if Assassins is the child you put up for adoption, so many of your creative children still live firmly under your own roof. Between 1977 and now, when have you felt that same thrill of possibility as when you first uncovered those assassin stories?

Well, I’ll mention my current project, which is in a state of becoming. I’ve written musicals all along since the 1970s, and a few of them have been produced here in Philadelphia. One production went from Philadelphia to a festival in New York, but nothing that’s achieved the level of acclaim or notoriety as Assassins.

My current project is one about Charles Dickens and his relationship with a young woman named Nelly Ternan, who was his secret mistress in the last years of his life. Again, it’s a historical idea, and it’s another idea where, as I began to do some exploratory research, I thought, wow, this is hugely promising. The material has both great historical significance, but also the opportunity to invent creatively and respond, and to use what I call creative anachronisms, so bringing different theatrical and musical languages to this world of Dickensian London.

That’s a project that’s got me very excited right now. I’m a couple of years into working on that project. But there certainly have been a few times when I’ve felt that tingle that says, oh, this is something that’s going to be worth spending a few years of my life on. I think that’s part of what I remain in pursuit of: that kind of tingle or feeling. Even though now I’m 70 years old.

Charles is on Substack, too! His newsletter is called Making Musicals Matter, and I heartily recommend it to all Sondheim Hub readers.

Would you like the full Sondheim Hub experience? Our paid subscribers receive a weekly Sondheim Supplement, featuring our latest crossword, an exclusive additional essay, an extended interview, and other bonus content you won’t find anywhere else.

The Sondheim Hub exists solely thanks to the generosity of readers like you. Your support means the world to us. If you find our work valuable, we’d be thrilled if you’d consider upgrading your subscription. Click here to explore our various subscription options.

One additional point: the Dramatists Guild and the Musical Theater Lab created a program for new musicals and welcomed submissions in 1979/1980. I was running the Musical Theater Lab at the time and Sondheim was on the board. He looked over the titles of all the submissions and said, "Assassins looks interesting. Could you send a copy over to me?" The DG/MTL project never not off the ground, but that is where Charles first submitted his Assassins.

Assassins is my favorite show 🥲 and had no idea that the idea originally came from someone else!! I'm grateful things unfolded the way they did, and I'm grateful for Charles Gilbert for coming up with this incredible show 🥲🙏