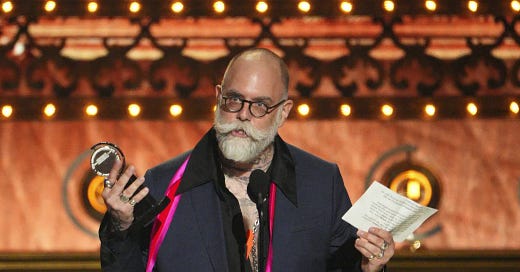

It was such a pleasure to speak to three-time Tony Award-winning scenic and costume designer David Zinn about his work on Here We Are, ahead of its European premiere at London’s Lyttelton Theatre. We discussed the challenges and pleasures of design, the visual language of Sondheim’s final musical, and those all-important slippers… Our conversation begins below:

It’s so good to meet you. I’d love to start with your own Here We Are journey. What do you remember of those initial conversations? And what does the process of bringing the show to London look like from your perspective?

We started thinking about Here We Are in 2015 or 2016, and we were always really attracted to it being in a non-traditional theater space. Even at that point, when Stephen and David [Ives] had only gotten through most of Act I musically, we knew it was likely Steve’s last musical. His oeuvre has become so deeply beloved and canon that we wanted to free this last work a little bit from his context, so that people could truly experience it as a new piece. Here We Are is a period on the end of a sentence, but it’s also a new work, and so I think we always wanted to re-contextualize it.

Then it seemed like it wasn’t going to happen, and then it seemed like it was going to happen, but we didn't know where. When we started making it for The Shed, there was some initial conversation about it being a co-production with the National. Never a deal—just a conversation. But that meant that even though The Shed is a huge black box space, I did spend some time with the ground plan of the Lyttelton. That conversation never went past a certain point pretty early on, so then the show really formed itself around The Shed.

We tried to make Here We Are something that when you walked in didn’t feel like you were coming to a revival of a beloved Sondheim musical—we wanted it to feel like a new event. So what’s been happening is that we’ve spent some time—which we’re mostly done with—rejiggering it just to make sure that all the various elements fit in the Lyttelton. Most of them do. Some of it has needed to be reconceived and redesigned in ways that either feel neutral—just “this used to do this and now it has to do this”—and in one case, in a way that actually feels really great. The Shed was 23 feet tall and you couldn’t go up: you could only go back or to the side. Having the Lyttelton’s traditional fly space has liberated a few things, which has been really nice.

The set from New York was put in a big shipping container and sent over, and the clothes have been sent over. Casting is done. Now we’re just making the things that either are changing or haven’t survived. We need to start to think about how to incorporate these new people in the world of the existing clothes and palette and vocabulary.

There’s just one thing that we’re trying to figure out: a way to defamiliarize the Lyttelton a little bit. It has a strong identity, a strong physical character that’s hard to shake. But we’re interested in just making it feel a little different than when you normally walk into the Lyttelton, which I think will be fun. But cut to April, and we’ll see how we did!

For the visual language of Here We Are, did you look back to the Buñuel films? Or were you always thinking about this as something totally new and distinct, that could visually go in any direction?

I think the spirit of the films has been more important than the literal visual vocabulary of them. The genesis of the design came out of a bunch of things, but you can find one of them within The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. In that film, they’re like, “Okay, we’re going to this restaurant,” and then suddenly they’re walking in a field. Smash cut, we’re walking in a field—smash cut, we’re now somewhere that’s not in a field. These restaurants, these places they go, appear and disappear—and they need to. We wanted to find a way to do that.

There’s an element of not knowing what’s going to come next, and those things can be destabilizing as an audience member. I think trying to keep the ball up in the air and keep people from knowing what’s coming next has been one thing that’s been driving us throughout this process. My whole job is taking very practical concerns and trying to solve them in ways that don’t feel like I’m solving practical concerns—trying to turn those into a kind of poetry that feels inevitable.

If you think back to your earliest ideas about the look of Here We Are and compare them with what we see today, how much has remained intact? Were there any significant surprises along the way?

There was a super early instinct I had when we were talking about it, years before the pandemic and all that jazz. Joe [Mantello] started with this problem of “cool, we’re all sitting down in a restaurant and then that restaurant has to go away, and what we don’t want to see is a bunch of people lifting up their chairs and moving them to the side.” Pretty early on, I was like, “Well, what if the signs of the restaurant are the things that they’re sitting on?” So you introduce the place, and that becomes the table and the seating, and then it can go away again.

That idea stuck, which is a little bit of a surprise to me, because sometimes those first ideas are just a way to get to another idea—but it stuck with Joe. I was really interested when we came back to it after a few years. He was like, “I think there’s really something in that.” There’s a kind of absurdity in not furnishing the restaurants.

The thing that surprised me was that Act II is so different. They finally land in a place that behaves by a different set of rules of time. I don’t know that I would have imagined that was ever going to be such a complete environment. When we were walking around the Public Theater, which is where we were going to do it initially, it was like “Oh, cool. Well, maybe the whole place sort of feels like the Embassy.” But the specificity with which we landed in a few of those locations has been a real delight to me, and also to figure out where to hide those locations—where to bring them in and take them away.

I love how you’re highlighting the creative problem-solving aspects inherent in your craft. I wondered, do you ever experience an equivalent to what we might think of as writer’s block?

That happens. It doesn’t happen all the time, but it definitely happens. I’m nodding my head right now, because I’m actually just over a hump on another project that was offering a lot of those. I’m 56, so partly the thing that helps me is I know there will be a solution. I’ve done it enough that I know I’ll get to a certain place, so I try not to panic. You know the things they tell you to do when you’re having trouble sleeping? Don’t freak out about it. Just get up and read a book. Take a deep breath. I try to follow those things. Don’t freak out: it will come.

As a designer, as a writer, as whatever, you bring all this research. You fill your lunchbox or your toolkit with all the things you need. Sometimes you forget to bring everything that you need, and what’s dumb is to go back to the same backpack and keep looking at it, being like, “It has to be here.” Use these moments as an opportunity to try to surprise yourself, to look at things that you wouldn’t normally look at. Look at the way other artists have solved either similar problems or dissimilar problems. Ask yourself, how do I get out of the headspace I’m in that took me here? And how do I refresh that?

So many of the original Sondheim productions seem to have such a strong visual language. I know that you took Here We Are on its own terms—moving away from Sondheim’s context, as you said—but do any of those productions resonate with you more generally as a designer?

Yes, it’s true that we were working hard at making Here We Are not feel like something you had seen before. But something that’s in my mind a lot as a designer, just in general, is Eugene Lee’s beautiful set for the original Sweeney Todd. I love that Eugene’s work—and in other work of his, whether Sondheim or not—really was about what the real objects are. It’s not scenic. I mean, it is scenic, because it’s assembled on stage—but they’re real objects. They’re not objects pretending to be other objects. They’re not wood painted to look like other wood. They’re just there. He’s like “What about a factory?” So you go get a factory and you take it apart, and then you put it on stage.

It wasn’t like I remembered Sweeney Todd when we did Here We Are—but I love that kind of thinking. It’s about not thinking of the spaces as scenic solutions, but as how you make a space that has some honesty and energy and charge to it. It isn’t about fakery, but it is about the ghosts that architecture has. I didn’t see Boris Aronson’s A Little Night Music. I’m sure it would have blown my mind at that moment, and I have a great respect for it—it’s just not how I solve problems. The way that Eugene, 40-something years ago, brought that particular kind of very modern problem-solving to that musical is a real touchstone for me.

And finally, thinking about Here We Are again, I couldn’t resist asking you about those slippers…

Those slippers went through a lot. Part of what’s hard about the show is that, if you know The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, they’re walking all the time. And we do a lot of walking in the show, especially in Act I. Marianne’s shoes, and Claudia’s shoes too, become these incredible fetish objects that bespeak a kind of high fashion style, but they also have to walk around in them every night. So in addition to wanting to fulfil some things about the way they looked, they were uncomfortable.

Shoes are always a living nightmare when you’re a costume designer. Also, the kind of shoe that he’s describing is not in favor. There aren’t a million of them out in the world at this moment. Even finding such a magical object was… a process.