A Conversation with Mark Lambert

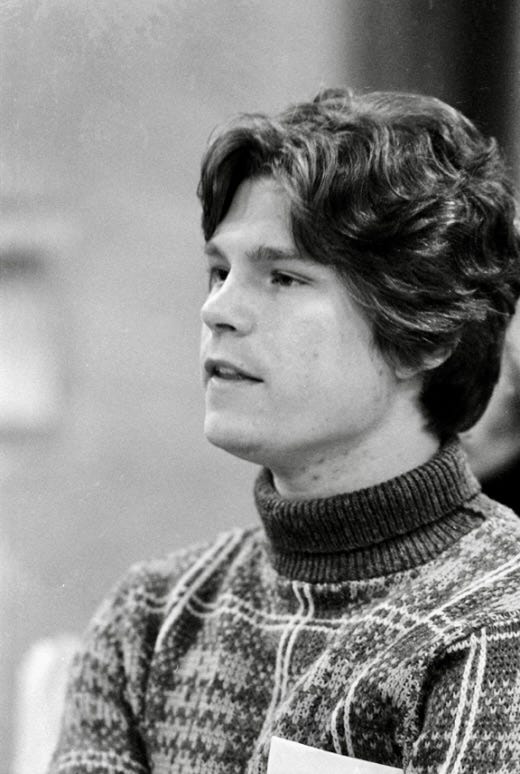

We speak to Broadway's original Henrik Egerman (A Little Night Music)

It is a rare and wonderful thing to speak to someone who originated a Sondheim role on Broadway. I recently had the pleasure of speaking to Mark Lambert, who in 1973 brought Henrik Egerman into the world, in the first production Sondheim’s A Little Night Music. His career since has been one of genuinely astonishing breadth, both within the arts and entertainment industry and beyond it too. Our conversation begins below:

Could you take me back to the first time you heard about A Little Night Music? How did you first become involved?

I was quite young. I was 20 at the time, and I had been performing in a singing and dancing group in San Jose, California, and they had talent scouts. One came to a rehearsal and sat in the back. Nobody knew who he was. And up he came, and he approached me. Without introducing himself, he said, “I need to talk to your parents.” And sure enough, he did. And I went to LA that summer. And almost immediately, because of the way in which I had entered the scene with a talent scout, I had a manager and really good agents on both coasts and so on. I was studying with the best: Joan Darling for acting, and David Craig. David was the progenitor of the actor in song technique, which is not singing and not acting. This was many years ago, of course, but Steve Sondheim once said, “I have seen three great auditions in my life that were not coached by David Craig.” And David was not only my artistic mentor; I became a family friend and repaired his daughter’s car and all that sort of stuff.

It was through David that I heard about Night Music. I had a proper audition on the West Coast. As I understand it, I was the only person cast from the West Coast, and I think I was the last person cast. And the first was Victoria Mallory, who I would play opposite and of course be married to for 40 years. When I got the sides for the audition, Joan Darling, my acting coach, who was quite wonderful, read it and she said, “You’re not going to be able to make this work. Go ahead and do your audition, but you’re not going to be able to make it work.” And as it turns out, it was quite a different story. So I was cast in California and came to New York, never having been to New York City before, and off we went.

And when you were going through that audition process, how aware were you of Sondheim’s work up to that point? Had you seen any of his shows before, or was that not really a part of your world growing up?

It really was not. I grew up in San Jose, California, which was a hick town at the time. I discovered that I could sing purely by accident. I was on the diving team in high school, and the drama coach approached me and said, “Do you sing?” And I said, “I don’t know,” and ended up playing young Joe for the senior production of Damn Yankees. But that night I was in the bathtub, and I tried to see if I could sing, and yeah, I could. And in fact, because of Joan Darling’s wonderful coaching, I started to guest star on TV when I was in LA. But the very first job I ever had was supplying the voice for “Tomorrow Belongs To Me” in Bob Fosse’s Academy Award-winning movie, Cabaret—and I’d never had a voice lesson. I didn’t really know anything about musical theater. When I discovered I could sing, I got interested in it, and I had my little record player. I played Sammy Davis Jr. Sings and Laurindo Almeida Plays, and a Jack Jones record, and I sang along with them and that’s how I learned to sing. So in answer to your question, I didn’t really know anything about anything.

That’s remarkable, particularly because your big number early on as Henrik is now considered one of the most challenging male songs that Sondheim wrote. Do you think that, in some ways, it was your lack of years of vocal training that gave you the confidence to just jump in and tackle a number like that?

The naiveté, you mean? Yeah, absolutely. We had our first day when we were singing through our songs in the rehearsal studio, and I sang “Later”—and Steve said, “Take it up a half-step.” He had written it so that the high note was a B flat, and it landed on a B that day. And the truth of the matter is I didn’t really know what a B was. I just knew it was a high note, and I sang the high note. The real challenge of singing that note, other than being seated, was that cello. Steve and Hal got me a cello, which I took back to my teeny weeny little apartment. I worked out the exact fingerings of the piece, so that under that high note, the hands and arms are working furiously. And I think it’s that of which I was most proud. Again, as a non-trained singer, I just sang the note. But hitting the note every night and doing this extreme physicality at the same time was a challenge. A cellist from the Philharmonic sent me a note saying how wonderfully well they thought I’d played the cello. So that was really my source of pride about it: the integration of those multiple challenges.

One of my favorite moments in any Sondheim show is when that early trio of songs [“Now,” “Later,” and “Soon”] come together. Do you remember the first time you, Len [Cariou], and Victoria brought that trio to life?

Yes, I do quite distinctly remember it. Len Cariou was of course tremendously professional. Victoria was a phenomenon, and Steve related to her in that way. At one point it was published that she had one of the most “glorious”—Steve’s word—“voices I’d ever heard.” She was an extraordinary person. As a musician, she was given a four-year, all-paid ticket to the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music as a classical pianist when she was a sophomore in high school, so she was a consummate musician. So she absolutely was right there, Len was right there, and I was too. And the very first time we sang it, it just soared, and it seemed to soar 600 plus times. And when you mentioned it, just the mere mention of it—my personal relationship with it aside—I got chills. I’ve pretty much had them through this entire recollection of that.

Steve and Vicky connected on a level that was unique. They remained friends. And I think it’s because, like Steve, Vicky was astonishingly realized on this earth, but never really of it. And Steve had the same kind of quality. He was just absolutely extraordinary in his ability to relate and understand, but somehow was just a little bit not part of it—and Vicky was the same.

After the show closed and Vicky and I got together, we used to offer a parlor trick to guests at our home. We would turn out the lights, turn on the record, and we would sing along with the trio. It was a reason to come have dinner with the Lamberts.

That’s so brilliant. Did any of your guests ever try and sing Fredrik’s lines?

No! That would have been wonderful had that been the case though.

I know that you’ve seen various productions of Night Music since—one of which, of course, featured your daughter Ramona. Is there part of you that still sees yourself as Henrik whenever you see someone else take on the role you brought into the world? Is it even possible to divorce such formative, physical, tangible memories from what you’re then seeing on stage, years later?

Yes, that’s largely the case. Again, I was trained as film actor, so I probably approached it quite differently than most. In fact, to immediately answer your question directly, I relive the feeling every time. I still remember the lines, and relive the feeling that attended the delivery of those lines.

But in terms of my performance, there was a particularly intense moment with Hal Prince in rehearsal. I was doing the scenes, and with a high level of consternation, he said, “You’re not doing it the same way every time!” I was a kid, trained as a film actor, and I said, “Hal, how can I do it exactly the same every time when I don’t feel exactly the same every time?” That did not play very well with Mr. Prince, by the way. And I did eventually lock down a performance, but it was every night fuelled by this method acting, which is the way that I was taught.

It’s fascinating to be taken inside that rehearsal room there. And you’ve had such a varied career since; it’s quite astonishing to look at the breadth of your activities, in fact. I wondered if there’s a particular memory that stands out to you from that particular rehearsal room, especially now that so many of the people in that room are so revered. Is there something from that time that you’ve taken forward into your other roles, particularly those that on paper might look quite different?

In truth, I of course analyze the script and have a sense of who the character is, and more importantly what their motivations are, what their goals are and all that sort of stuff. But when it comes to roll camera or curtain up, it’s about being present. And I think that’s the case whether it’s on Broadway or working in television, or in the subsequent things that I’ve done. When I worked with Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, his book The Power of Positive Thinking was the best-selling book in the history of the world except for the Bible. And he would speak, and he frequently asked me to speak also. And when I transitioned into medical research—not as a researcher, because clearly that’s not my skillset—but asking questions that need to be answered and creating collaborative environments is how I became chief of staff of a leading research institute. There were folks who understood the chemistry and the biology, but creating an environment in which people collaborated and their energies meshed was the key, and the productivity and the inspiration which attended those kinds of situations was the commonality.

There are skillsets and perspectives and disciplines that attend the business of acting and singing that I have found in my life to be directly applicable to making good things happen fast in the world. I consider that training to be my baseline. When I’m working with clients, I say, “My first job is to listen.” And then in organizing a truly global organization like the Global Sepsis Alliance, once having listened to all parties, then there’s the question of creating a mutuality of vision. And once having done that, that’s when you create a call to action and that’s when it enters the world. But those two elements—listening and creating a mutuality of vision—are directly applicable from the performance sector.

I’m absolutely agog. What a great story. Thank you so much for sharing this. There is no one that was touched by Sondheim that wasn’t sent in flight to the highest heights. Amazing.♥️