A Conversation with Michael Mitnick

Michael Mitnick is a playwright, screenwriter, and songwriter whose theater works include Scotland, PA and the Drama Desk-nominated musical Fly By Night, and whose film credits include The Current War and The Giver. In this conversation, we explore his relationship with Stephen Sondheim and his work, how Sondheim’s approach to surprise and craft influences his own writing across different mediums, and his latest project: Hello, Broadway!, a children’s book introducing young readers to musical theater. Our conversation begins below:

Thank you for reading! Upgrade to paid to support our work & receive our weekly Sondheim Supplements: exclusive crosswords, additional essays, extended interviews, & more.

There are so many strands to your relationship with Sondheim and his work. When did you first encounter his work, and when did you first encounter him in person?

I started writing songs in high school. About that time, I started to become as interested in the writers of the songs as the songs themselves. I have pretty severe tinnitus, and so when I would go to sleep growing up, I would always have to listen to music. My parents brought down their record collection, which was mostly show tunes, so I had shows like West Side Story and Forum drilled into my head over and over again. Over time, listening to them, I realized that these shows all have something in common: they’re all a bit deeper. And that’s when I started to pay attention to the names on the covers.

I started writing songs and wrote some little musicals with my friends in high school, and I became obsessed with Merrily We Roll Along and Into the Woods. I started to get a bit deeper into Sondheim shows. I did the thing that most young songwriters do, which is to send our early work to try to get any kind of positive feedback. I wrote my first letter to him in 2000, and of course he wrote right back. He was writing Wise Guys at the time, and said that he would wait to listen because he didn’t want to be influenced by my writing. That’s something that he wrote to many people, but it’s such a charming way to decline.

From that point, I stayed in touch, writing letters, asking his advice. I worked as an assistant to Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens on three musicals, and over time I would ask Sondheim for general career advice.

I didn’t meet him in person until I was in grad school at Yale Drama, after a talk at Avery Fisher Hall. We were introduced through a mutual friend, I said hello to him, and then later that year, the playwright John Guare, who was one of our professors, took us over to his house for an afternoon. That was just incredible. I remember I was talking to the other two playwrights with me, saying it’s really important you don’t eat up time asking the questions that have been asked of him a million times over. That’s really how I first got in touch with him. We had some dinners and some more visits over the years.

The last letter I got from Sondheim was on the day that they announced his death. The postman came and gave me the envelope, and I was like, “Oh, I recognize that envelope.” It was a little note where he said congratulations on the birth of my son, Harry. I’d sent him the announcement. And then an hour later, the New York Times push notification came. I was not his friend or anything like that, but I was someone who tried to absorb as much as I could from the periphery.

I love that idea of absorbing as much as you can of an artist and their craft. You’ve been described as the world’s largest Sondheim collector. Does that impulse come from the same place—a desire to gather that creative stardust?

In terms of stardust, I will tell you that when the cleaners came to vacuum everything out of the daybed, there were about three buckets of black genius that I did not hold on to.

I started collecting this stuff, weirdly, when I was in high school. I guess it’s not that odd now that you can get everything through the computer, but this was when you’d write letters, and people would send you discs through the mail. You’d trade things. That’s when I got some of his early songs from Phinney’s Rainbow and All That Glitters. The 92nd Street Y talk was probably the greatest Sondheim lecture there is, and that’s all about craft. For me, it suddenly became, “Okay, well, I want to know what all of it is.” And that involved tracking stuff down.

Then I had to put it somewhere. So it turned into a collection, and when you’re just doing it in the background for 20 years, it adds up. People then pop up and they go, “Hey, do you want one of the Mandy Patinkin standees from Sunday in the Park with George?” Or, “Do you want this Wizard of Oz book that he wrote his name in when he was a child in his scrawling handwriting?” But the goal has been to put it all together into an archive that now people are using. And then, at some point, I’ll find a place where I can hand it off.

When you’re writing, do you lie on that daybed? And for people who might not be too familiar with that piece of furniture, could you describe it?

Stephen Sondheim would write lyrics reclining, and he would often do that on a daybed. He had a daybed in his townhouse—although that physical piece of furniture changed many times, and those have been preserved. And he had a daybed in the country house, too, behind the piano. That’s where he would have written a lot of Into the Woods, Assassins, Passion, Road Show, and Here We Are.

The stipulation with my wife was that if I brought the daybed into the house, it had to be something we could use. The kids lie on it and read books, and I push the dog off it when I can, but when it’s possible, I’ll use it. And then eventually I’ll donate it somewhere.

You’ve spoken elsewhere about growing up loving magic, and how important the element of surprise is to writing. Is that something you get from Sondheim’s work, too?

Absolutely. Sondheim really believed in the power of surprise. He said the two biggest sins are to bore an audience and to confuse an audience. Keep things constantly surprising—and if that’s happening, then at least you have something going on where people can’t really look away.

Also inherent in the idea of surprise—in the context of a magic trick, or of a joke, or of a chord change—is that the more you listen to something, the more you discover things. It’s like, “Oh my goodness, he’s actually preserving the same rhyme sound through that stanza structure every time it recurs.” You have a lingering tonality in your head beyond just the fact that it happens to also be a proper rhyme. All of that is so deeply layered throughout all of his work, and it pays dividends. All of Sondheim’s work is constantly shifting and growing and surprising.

Do you still feel his creative hand on your shoulder in your own work? Do specific projects come to mind where you’ve felt his influence particularly keenly?

With the stuff that I would write, and the stuff that I write now, I do think: what would he think of it? It had to do with trying to keep my work at its best, so that I wouldn’t embarrass myself. It was the same thing when I showed songs to Ahrens and Flaherty: I knew that they were going to call me out on everything that they recognize could be better. So it’s a way to try to keep myself from saying, “This is good enough.”

I remember in grad school I told Sondheim I was writing a musical about Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse and the race to light up America. John Weidman had come up to Yale to talk to us, and he told me at lunch, “Steve and I were trying to work on this same idea for a little while.” So then when I later asked Steve about it, he said, “Oh yes, I remember that. It’s a really incredible piece of history, but the problem is that the character of Edison—the character and Edison the real person—didn’t change. He was staunch in his beliefs, and there was no contrition.”

But when I did send the musical to him, he said that he liked that the music was based on the motif of AC and DC. He said something like, “If I had thought of that myself, I would have been tempted to write it,” or something really sweet. I think anybody who got to show something to him remembered it forever. It’s the same way that he would read a bad review of his work, and it would become tattooed on his brain, and he could recall it 80 years later, word for word. If he said a nice word to you, it’s also tattooed on our brains forever.

And your Edison/Westinghouse musical became The Current War film [2017, starring Benedict Cumberbatch & Michael Shannon], which makes me think about finding the right medium for the right story. Broadly, how do you know what works best where? Is it instinct, or more about practical circumstances?

You nailed it across the board. Some things are tied to the circumstances. But I believe that stories can be told in many different ways. When I hear people say, “Who ever thought that was a good idea for a musical?” I go, “Well, you can see all of their names. They’re written in the pages.” And Sondheim would say that someone could musicalize the phone book, if they did it in an interesting enough way.

That said, a lot of the stereotypes of what makes a good musical are true. For instance, characters singing with really big wishes or wants, clear expressions of those wishes. Even for Sondheim’s characters, who are largely often ambivalent, it’s big ambivalence, big swings in both directions, back and forth.

After I had written The Current War as a musical, and I was starting to get into screenwriting as well, my agent suggested I adapt that, and he meant that I should also do it with the songs. But for some reason, I just thought it would be better if it was done more realistically. Luckily, I’d done a couple years’ research already, so it didn’t take that long to write.

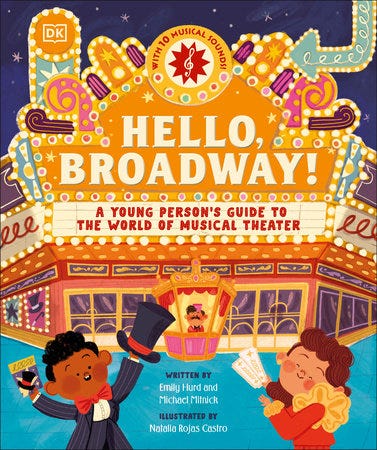

Speaking of different formats, you’ve co-written a children’s book, Hello, Broadway!, which comes out soon and is available to pre-order. I’d love to know about that collaboration.

When you have kids, you buy these books that have push buttons that play tiny clips of songs. There are many for ballet and opera, but there are none for musical theater. So an old friend of mine, Emily Hurd, with whom I co-wrote the text of the book, had this idea to do it with show tunes. I thought it was a really good idea.

One of the reasons that it hadn’t happened is because so many of the songs—most of them, in fact—were under copyright until more recent times. Also, tracking down disparate rights can be very time-consuming. But because I worked for and was friends with different songwriters, it was easy to just text them, gauge their interest, and then license the songs officially through the publishers.

As I mentioned, I grew up listening to musicals. Obviously, I like musicals because I write them. But I feel like this is a way to get kids addicted now at a much younger age, where they can sit there and, on their own, press a ten-second clip ten million times until their parent gets them the full album. It’s a way to hopefully bring new people to the genre.

When you know so much about a subject this rich, how do you begin to distill it all?

The initial book is to introduce children to what a musical is, and specifically what the experience of attending one is like. Ideas as basic as you’re not supposed to talk while the people on stage are performing, or that there’s generally a break in the middle where you can try to go to the bathroom.

But also, it’s about introducing ideas like what a solo is, what a duet is, that musicals often start and end with big songs, that there’s such a thing as tickets, that you get dressed up when you go to the theater. Although as I say that, it’s no longer the case; I’ve seen flip-flops on opening night. But that’s the goal. And then, in future books, each book will be a musical.

Find out more about Michael Mitnick’s work by visiting his website. Hello, Broadway! is available to pre-order at this link.

Would you like the full Sondheim Hub experience? Our paid subscribers receive a weekly Sondheim Supplement, featuring our latest crossword, an exclusive additional essay, an extended interview, and other bonus content you won’t find anywhere else.

The Sondheim Hub exists thanks to the generosity of readers like you. Your support means the world to us. If you find our work valuable, we’d be thrilled if you’d consider upgrading your subscription. Click here to explore our various subscription options.

And if you enjoyed this piece, please click the heart button below (or at the top of the page if you’re on Substack). It genuinely helps more people discover us. The algorithm of life is a powerful beat…

Michael is the best and such a generous person with his theatre knowledge, too.