A canon is one of the oldest and most satisfying kinds of musical architecture.

In its simplest form, it’s a melody that harmonizes perfectly with itself when begun at different times. You have almost certainly known several musical canons since you were very young indeed. Think of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” “Frère Jacques,” or “London’s Burning.”

But canons can become dizzyingly complex: a composer might vary the time interval between entries (from a single beat to several measures), the pitch interval (the second voice might start, say, a fifth higher than the first), or the speed (one voice might sing twice as slowly as another). And a composer might transform the melody itself: we might hear it played backwards (in retrograde) or upside-down (inverted).

What makes canons so compelling is that they create harmony—often complex harmony—through pure democracy. In a strict canon, each voice follows exactly the same musical path; they simply start from different points. The result can be anything from meditative to frenzied, from prayerful to playful, but it always carries that satisfying sense of pieces of a puzzle fitting perfectly together.

And who do we know who really, really liked puzzles?

Composers are not always constrained by the strict rules of pure canon. Like a photographer who deliberately lets light leak into their camera for artistic effect, a composer will often loosen the mathematical precision of canonic writing into something more fluid. Generally speaking, we might call this imitative counterpoint. Here, one voice might echo another with small variations, or a melodic fragment might ripple through different voices like a stone’s splash across a lake. These techniques maintain the psychological effect of a canon—that pleasing sense of echo and reflection—while allowing more freedom for dramatic expression.

In musical theatre, this flexible approach to canonic writing can be especially powerful, allowing a composer to suggest the mathematical precision of Bach while serving the more immediate needs of character and plot.

Let’s begin in the 1950s. The young Stephen Sondheim supplied lyrics for West Side Story (1957) and Gypsy (1959), both works that now indisputably belong to the musical theatre canon (in the word’s other sense of suggesting works that are generally agreed to have achieved the status of classics, serving as standard-bearers of quality and/or cultural significance). But each of these shows provides us—and perhaps the young Sondheim—with plenty of canonic inspiration in the musical sense, too.

In West Side Story, Leonard Bernstein shows us how canonic techniques can create layers of emotional resonance. The yearning melody of “Somewhere” is shadowed throughout by its own echo in the accompaniment, a measure behind. The effect here is of always reaching, of almost-but-not-quite touching. And in a show with tragic separation at its heart, we feel that effect particularly keenly. This is not a strict canon—Bernstein allows himself the freedom to vary the answering phrase—but it is a nice example of similarly imitative writing serving theatrical storytelling.

Bernstein returns to a melodic imitation of the “Somewhere” melody at the very end of West Side Story. Here, the canon is strict, albeit very brief. It cycles around, as if it could continue forever, were the upper voice not interrupted mid-phrase by the pause before the show’s final three measures. It’s a masterful depiction of both crushing inevitability and the sense of a line—and a life?—cut short.

Jule Styne, meanwhile, shows us how canon can serve pure comedy. Near the end of Gypsy’s “You Gotta Get a Gimmick,” Tessie Tura, Mazeppa, and Electra come together in a brief but perfect canon, each entering a measure apart with identical musical material (I have highlighted each of their entrances below). The effect is both musically satisfying and dramatically amusing, these three wildly different performers finally finding common ground in the most mechanical of musical devices:

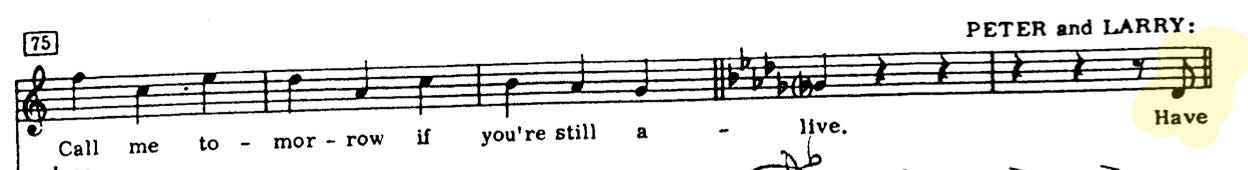

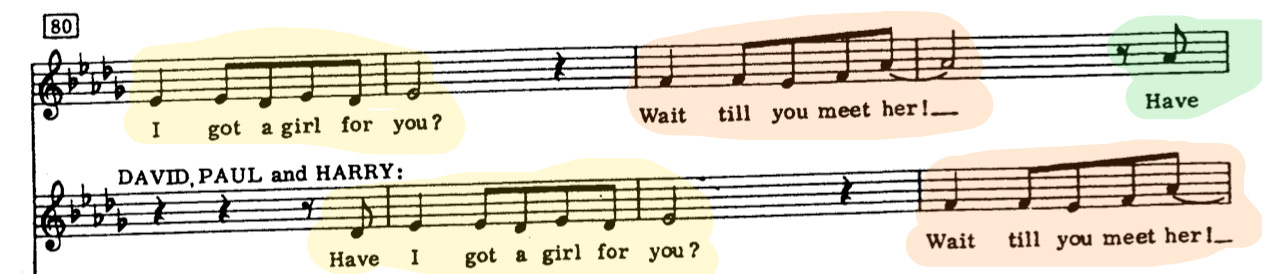

In Company, there is a brief but satisfying two-part canon to be found in “Have I Got a Girl for You,” as Peter, Larry, David, Paul, and Harry all attempt to set up the perpetually single Bobby with various potential partners. The effect of this unison canon, its voices displaced by a single three-beat measure, is one of mounting social pressure—of something decidedly claustrophobic from Bobby’s perspective.

Notice how each short phrase accommodates its own echo: the words “Have I” and “for you,” exactly one measure apart, are set to the same D♭-E♭, meaning that the first and second statement of that line overlap seamlessly (look at measures 80 and 81 below, highlighted in yellow). The sustained “her” that ends the next phrase is an A♭, which harmonizes comfortably with the Fs and E♭ that we hear below it (see measures 82 and 83, in orange). The third phrase (at measure 84, in green) matches the first; however, you will notice that, here, the answering phrase is cut short. “Hoo, boy!” is a brilliant way of allowing the second voice to catch up lyrically with the first; both vocal lines make complete sense lyrically, despite the curtailment of the lower one.

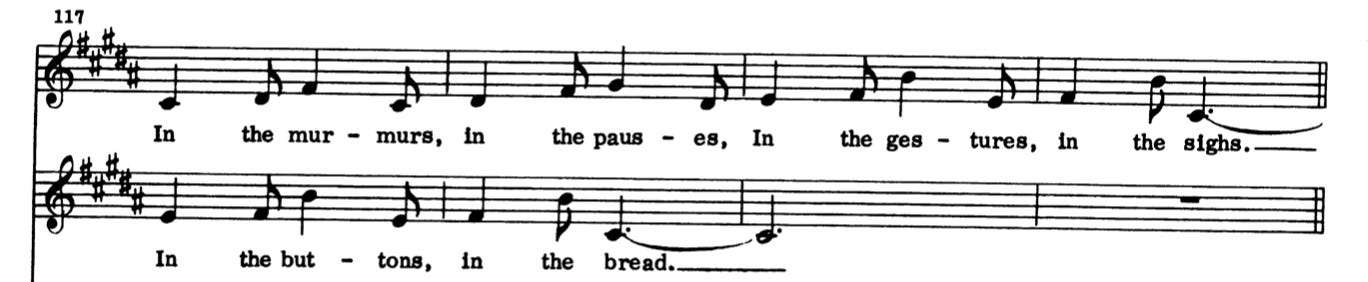

A Little Night Music’s “Every Day a Little Death,” meanwhile, shows us how Sondheim was able to use canonic writing to explore shared emotional experience. This is another unison canon, but at the more relaxed interval of two three-beat measures. The passage you see below is in strict canon. Charlotte and Anne sing precisely the same notes—surely a sign of the extent to which their experience of marriage is a shared one.

But you will notice that their words, after the first titular phrase, are not shared.

The phrase “people, places, and things” is often said to represent the essential components of storytelling, memories, or experiences. Well, look at how Sondheim divides up those elements. Charlotte speaks of places (“parlor,” “bed”) and things (“curtains,” “silver,” “buttons,” “bread”). Anne, meanwhile, tells us exclusively of things that relate to people (“lips,” “eyes,” “murmurs,” “pauses,” “gestures,” “sighs”).

Compared to the canons we’ve looked at so far, the one found in “Perpetual Anticipation,” near the beginning of A Little Night Music’s second act, is more fugue-like by some distance. It is a much more complex musical animal, and the way it operates shifts and changes as it goes on. This is a three-voice unison canon, and the time interval between the entry of each voice is irregular. There are five measures between Mrs. Nordstrom’s first note and that of Mrs. Segstrom. Mrs. Anderssen waits a further 10 measures before she joins the texture, precisely twice the amount of time. Each entry is highlighted in green below.

It is not until measure 22 that Mrs. Segstrom (the second entrant) diverges from Mrs. Nordstrom’s lead: her “It’s too unnerving” is the first lyric that she uniquely contributes, and the “-ing” of “unnerving” gives us our first pitch which does not fit precisely within the canon. This phrase, and the earlier one it corresponds to (beginning at measure 17), is highlighted in pink.

For the next few measures after this “It’s too unnerving” phrase, the upper two voices are freer as they all aim towards measure 28, which acts as a kind of musical punctuation mark within this canon. Mrs. Anderssen, you might notice, only has time to deliver one phrase in strict imitation of the other voices, before she too (at measure 26) contributes a unique thought for the purpose of reaching measure 28 tidily.

At measure 28, Sondheim begins his canon again—but it is now a minor third higher, and the time interval between entries has been reduced to two measures. Disregard the pitch of Mrs. Nordstrom’s first syllable (that F♯ just before measure 28) and you will see that this, initially, is also a strict canon. Each entry is highlighted in green:

From measure 34, you will see—just visually on the page, even if you do not read music—that the canonic writing comes to an end. Lyrically, Mrs. Nordstrom and Mrs. Segstrom speak with one voice from measure 34 onward, and Mrs. Andersson joins them just two measures later, for the satisfying three-part harmony of “Keeping control while falling apart.”

In those measures, Sondheim brings us back to where we began, harmonically speaking. A third canon begins—but this time you will notice that the time interval between entries is just one measure! Again, each entry is highlighted in green.

Though this final canon is brief, it is particularly impressive that Sondheim plots a lyrical path toward that final “heart” for each character that makes perfect sense in each case. Mrs. Nordstrom gives us the complete phrase: “Perpetual anticipation may be good for the soul, but it’s bad for the heart.” Mrs. Segstrom says, “Perpetual anticipation may be good, but it’s bad for the heart.” And Mrs. Andersson simply offers, “Perpetual anticipation is bad for the heart.”

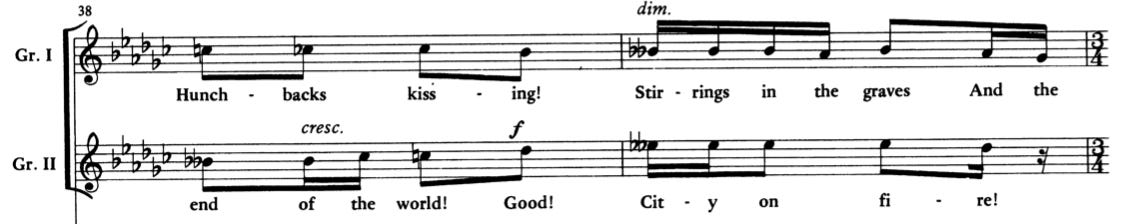

Remember I mentioned “London’s Burning” as one of our best-known canons from childhood? In Sweeney Todd, Sondheim gives us his own canon—albeit one a little less childlike—in which London is likewise said to be burning.

The “City on Fire” canon is musically and dramatically thrilling, and its voices are displaced by four beats throughout. I use beats rather than measures to describe the time interval because, as you can see, the time signature switches between 2/4 and 3/4 despite the canon being consistently displaced by four beats. This has a brilliantly destabilizing effect, perfect for a chorus of lunatics out of step with not only each other (i.e. the canon itself) but with society as a whole (i.e. the wider musical environment). Explore this for yourself by choosing any word sung by Group I below (the upper voice) and finding where that word appears again in the lower voice. As you’ll see, it always falls precisely four beats later, despite the two relevant measures not always corresponding visually (because of the shifting time signatures).

We encounter a similarly propulsive canon in the Act I finale of Into the Woods, “Ever After.” It is, though, a more orderly proposition than either of the two canons we’ve just looked at (in “Perpetual Anticipation” and “City on Fire”). The three voices of this canon enter two measures apart—and the third voice enters a fifth higher, like the answer to the subject of a strictly written fugue.

Though the texture does become busy, look at how Sondheim provides space for each new group to be heard, initially at least, as they enter. Each new voice asserts itself with its most rhythmically dense material first. And it is thrilling, of course, when all three voices coalesce at measure 90 (“You can have your wish” and so on), as we hurtle toward the emphatic “Into the woods” statement that begins the next section of this number. The overriding sense here, as befits this “happy ever after” moment of the show, is of characters propelled inexorably forward, toward a common goal.

Again and again, Sondheim uses canons in such a way as to make this rigorous musical form feel dramatically inevitable. From the chaotic energy of “City on Fire” to the mounting social pressure of “Have I Got a Girl for You,” and in the measured anticipation of those three ladies in A Little Night Music, Sondheim’s canons never feel like purely musical exercises. They are technically brilliant, but they emerge naturally from the dramatic moment—often so seamlessly that audiences might not even realize what they’re experiencing.

And isn’t that true of so many of Sondheim’s musical puzzles? Even as they demonstrate his formidable technical mastery, they never lose sight of the story being told.

I appreciate musical analyses as part of the diet here.