Someone in a Room Where It Happens

Stephen Sondheim, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and the art of historical perspective

So often, history is made behind closed doors.

In 1976, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman placed a boy in a tree overlooking the treaty house where Japan’s isolation was about to end. Nearly forty years later, Lin-Manuel Miranda positioned Aaron Burr outside a room, consumed by the political maneuvering within.

In each case, what might seem like a limitation—restricted access to a crucial historical moment—becomes the very source of the drama. Sondheim and Weidman turn a diplomatic milestone into a meditation on memory and witness; Miranda, meanwhile, transforms a locked-door deal into a fevered anthem of exclusion and ambition.

These numbers, “Someone in a Tree” and “The Room Where It Happens,” each take as their subject matter a historical event of enormous consequence: in Pacific Overtures, the “opening” of Japan to the West; in Hamilton, the Compromise of 1790. Our narrators, while present (in a manner of speaking), are peripheral. Yet it is precisely their marginality that allows these numbers to challenge conventional historical narrative. Interweaving the perspectives of those at the center and those at the margins, each number reveals something profound: history is shaped not just by what happens in the room, but by how it echoes in the memories of those who waited, watched, and wondered.

This challenge to traditional narrative begins with structure. Both “Someone in a Tree” and “The Room Where It Happens” build their narratives through layers of overlapping perspective. In Sondheim’s number, memory itself becomes a kind of architecture: the Old Man reconstructs his childhood experience through fragments of recollection, his younger self appearing to help piece together what he saw. His very grammar betrays the instability of memory: “I am in a tree,” he insists in one moment, then “I was there” in another, then back to present tense with “I am hiding in a tree.” This temporal slippage becomes both symptom and metaphor for how memory works—sliding between past and present, between observation and remembrance.

At the song’s outset, the Reciter confidently engages the Old Man, expecting a clear account of the historic event: “You were where?” … “If you please.” However, the Old Man’s memories are elusive and ambiguous: “Maybe over there… but there were trees then, everywhere.” Already, the unreliability of a single perspective is tangible. As the Old Man struggles to remember (“I was younger then...”), the music fragments and rebuilds itself, pieces of melody overlapping as if they themselves are only half-recalled. This is the music of glimmers, glimpses, glances.

The Boy, joining the Old Man, claims to “see everything.” Yet even between these two versions of the same person, the memory proves unstable. “Some of them have gold on their coats,” the Old Man recalls, but the Boy corrects him: “One of them has gold.” “Someone very old,” the Boy offers; “He was only ten” the Old Man counters. These contradictions destabilize any single version of events while illuminating a deeper truth about memory itself—how it shifts and reforms, how perspectives clash and merge across time.

The Warrior, hiding under the floorboards of the treaty house, introduces yet another partial view. This one is rooted entirely in sound: “First I hear a creak and a thump… Then they talk a bit… Angry growls… Much droning.” His observations, like those of the Boy and Old Man, are both vivid and incomplete. Each character holds a piece of the truth, but none possesses it entirely.

Taken together, these overlapping yet partial perspectives reveal the complexity of reconstructing the past—not just through conflicting truths but through the interplay of subjective experiences, each offering a sliver of the event. Still, with the Warrior beneath the floorboards supplementing the account of the boy still up in his tree, we experience something that might well raise an eyebrow on Fleet Street: those below serving those up above.

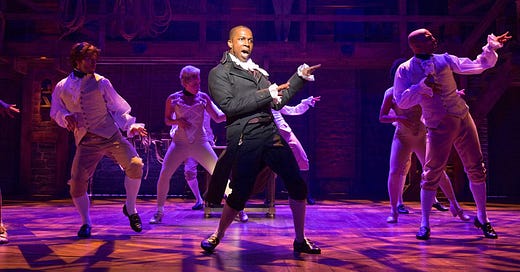

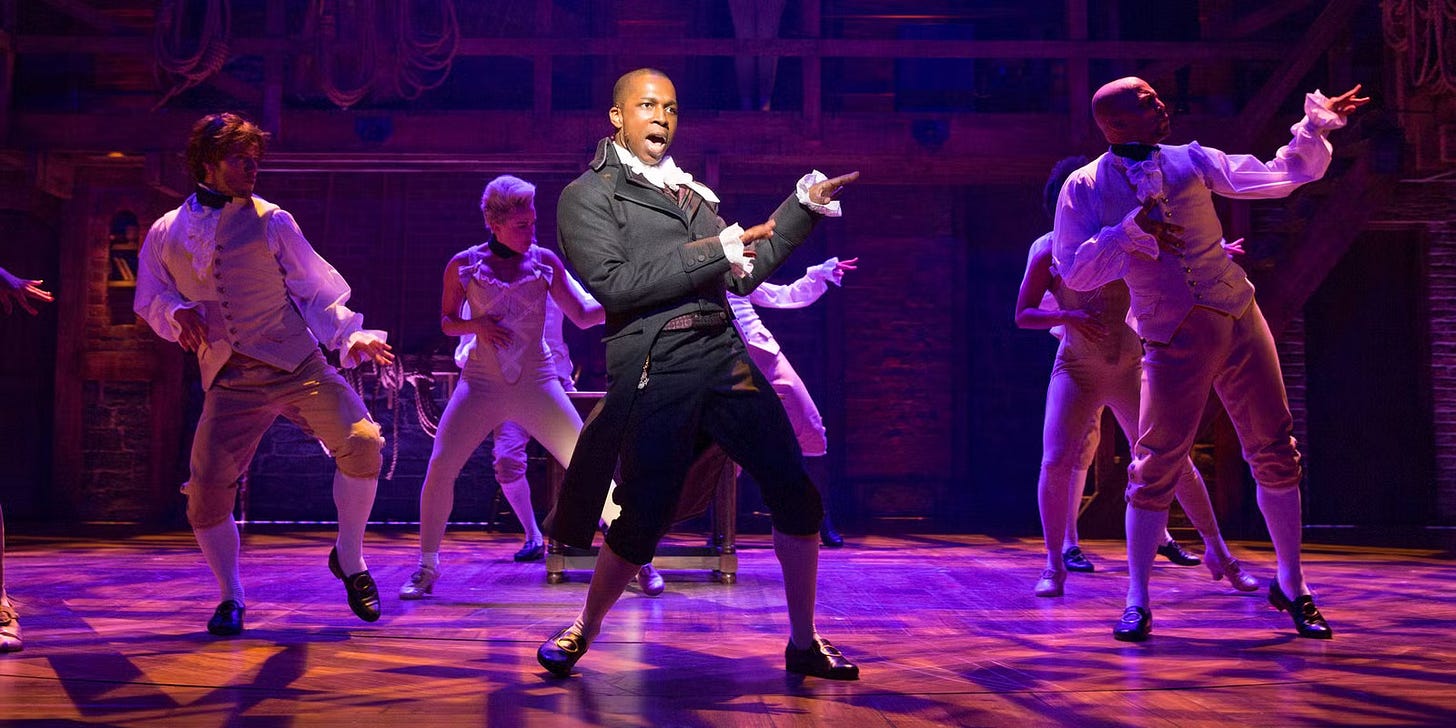

In “The Room Where It Happens,” Miranda transforms historical exclusion into dramatic catalyst. History here becomes an inaccessible space, shrouded in mystery and fueled by ambition. Unlike the witnesses in “Someone in a Tree,” Aaron Burr is entirely absent from the historic compromise he recounts, forced to piece together events through speculation, hearsay, and maddeningly cryptic exchanges with Hamilton. His narration radiates both bitterness and fascination—the voice of an outsider consumed by what he cannot access.

The scene is constructed like the political dance it depicts. Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton move with calculated precision: “Maybe we can solve one problem with another,” Madison suggests, “and win a victory for the Southerners.” Jefferson’s “Oh-ho!” radiates easy confidence. When Madison offers “Well, I propose the Potomac,” and Jefferson responds “And you’ll provide him his votes?”, we hear power arranging itself with practiced efficiency. This quid pro quo leaves Burr—and by extension, the audience—on the outside, watching as these men balance concrete political gains against the forces driving them: ambition, pragmatism, and what the ensemble will later call “the art of the compromise.”

Indeed, the ensemble is crucial throughout this number, their role shifting between Greek chorus and active participants in the political machinery. “Thomas claims,” they repeat, each iteration underlining that everything we learn is filtered through memory, agenda, and political spin. It’s in their mirroring of Burr, though, that they reveal their full power. They become almost an extension of his consciousness, shadowing him with an intensity that builds throughout the number. The line between personal frustration and collective grievance seems to blur; Burr’s words hit us like the cry of a crowd.

As the number nears its climax, though, the ensemble seems to turn on Aaron Burr. They join with Hamilton as he wields his rival’s own words against him: “Wait for it, wait for it, wait…” Each word is a wound. The ensemble, as if sensing Burr’s vulnerability, circles closer, joining in an overlapping call-and-response with Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison, and Washington: “What do you want, Burr?” For a man whose identity is inseparable from his political ambition, the question strikes at the very core of his being: to act, or to remain a bystander? To be, or not to be?

That, as they say, is the question.

Irony plays an important role in both of these numbers. Sondheim’s Reciter—framed throughout Pacific Overtures as the audience’s guide to Japanese history—finds his authority subtly but decisively undermined as the fragments of memory multiply. As “Someone in a Tree” begins, the Reciter declares, “What a shame that there is no authentic Japanese account of what took place on that historic day.” Yet this assertion, rather than grounding the narrative, becomes the very point of contention. The memories of the peripheral witnesses we meet throughout this number, though partial and subjective, feel deeply authentic. The irony is striking, and the Reciter’s seemingly objective posture seems to crumble under the weight of multiple, conflicting truths. In lamenting the absence of one “authentic” account, the Reciter reflects a common assumption that authenticity requires a singular, definitive version of history—a perspective that the rest of the number methodically dismantles.

The philosophical heart of “Someone in a Tree” emerges in its central metaphors: “It’s the pebble, not the stream / Not the building but the beam / Not the garden but the stone.” Through these images, we are invited to consider that historical truth might reside not in sweeping narratives but in minute details—not in the treaty itself, but in the cup of tea that accompanied it; not in the negotiation, but in the creak of a floorboard beneath it. When the Old Man insists “If it happened, I was there!”, he’s making a radical claim: that his fragmentary glimpses from the tree might matter as much as any authoritative account of the proceedings.

In “The Room Where It Happens,” Miranda’s irony operates differently but cuts just as deep. The paradox at the number’s heart is that Burr’s exclusion from the room generates deeper insight than his inclusion might have offered. In his obsessive quest to understand what happened, we learn not just about a political compromise, but about how political power itself operates. “No one really knows how the game is played,” Burr tells us—yet in his very exclusion from that game, he reveals its rules with devastating clarity.

This irony reaches its apex during Burr’s climactic exchange with Hamilton. Far from illuminating what happened in the room, Hamilton’s words—“When you got skin in the game, you stay in the game”—serve only to confirm Burr’s darkest suspicions about power’s relationship to access. The room, we realize, matters less than what it represents: the endless human drive to be on the inside, to be part of history’s making rather than its observation.

Both numbers reach their philosophical conclusions via strikingly different paths. In “Someone in a Tree,” the fragments coalesce into a kind of collective wisdom. The Old Man and Boy, initially separated by time, join together to assert “If I weren’t, who’s to say / Things would happen here the way / That they happened here?” This is not mere speculation about causality; it’s a radical repositioning of historical importance. The peripheral observer becomes essential—not despite their limited perspective, but because of it. When they sing “Only cups of tea / And history / And someone in a tree,” the mundane and the momentous are granted equal weight. The treaty signing and the tea drinking, the historical record and the personal memory, become inseparable parts of the same truth.

“The Room Where It Happens” drives towards a more unsettling conclusion. As Burr’s obsession reaches fever pitch, Miranda captures the gnawing tension between aspiration and alienation, crystallized in Burr’s bitter acknowledgment:

COMPANY

We dream of a brand new start—

BURR

But we dream in the dark for the most part.

The metaphor is telling—where Sondheim’s witnesses find meaning in their peripheral status, Miranda’s outsider discovers only an endless cycle of exclusion and longing. What we see and hear is now a swirling storm of desire, a fever dream of political ambition. The final “Click-boom!”, suggestive of both the sealed deal and the violence it portends, plants the seeds of the fatal confrontation to come. Burr’s transformation from analytical observer to consumed participant is complete.

These two masterpieces of theatre writing, separated by decades yet linked by their preoccupation with historical witness, offer profoundly different visions of what it means to be on the outside of history’s crucial moments. Sondheim and Weidman suggest that there might be no “inside” at all—that history lives most truthfully in its fragments, its peripheral perspectives, its overlooked details. Their witnesses, through their very limitations, reveal something essential about how the past echoes into the present. In Hamilton, Burr’s exclusion allows him to see power’s workings with unsparing clarity—but that very clarity only intensifies his desperate need to participate in it.

Stephen Sondheim and Lin-Manuel Miranda transform what might have been simple observations about historical access into complex meditations on perspective, power, and truth. Through the gentle wisdom of a boy in a tree and the fevered ambition of a man at the door, they suggest that history’s most profound truths might lie not in its moments of creation, but in its moments of witness—in the endless human effort to piece together meaning from fragments of memory and desire.

What a great post! We could even go out on a limb (pun intended) and consider how the Reciter is like Aaron Burr--(spoiler alert for those who don't know PACIFIC OVERTURES): after all, the Reciter reveals himself in the final scenes to be the Emperor who will out-technologize and surpass the West! How sharp of Miranda to craft his view of power structures and their systemic exclusion of citizens; how lucky of us to have yet another few of Sondheim's vividly drawn outsiders redefining the center of lived experience.