In 2009, Mark Stryker of the Detroit Free Press asked Stephen Sondheim what attracted him to the music of Benjamin Britten and Igor Stravinsky. Sondheim’s response revealed as much about his own artistic sensibilities as the music that moved him:

Their theatricality and harmonic language. Britten is more tonal, more modal. But Britten spikes it. There’s always some acid and unexpectedness and drama. Look at The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, which I think is a genuine masterpiece. When the final Purcell melody comes in — talk about drama! Stravinsky is the same. It isn’t just the dissonance of The Rite of Spring that makes it so much fun; it’s the drama in it.

Sondheim’s words offer a valuable window into his musical thinking. In Britten’s work, he identifies a composer who could honor traditional forms while subverting them—who could take modal and tonal materials and “spike” them with moments of startling drama. In Stravinsky, he recognizes that revolutionary impact comes not just from surface discord, but from deeper structural innovation. Both composers, he suggests, understood how to create genuine theatrical events within purely orchestral works. Let’s explore these two landmark pieces from a Sondheimian perspective, and consider how their sophisticated dramaturgy might illuminate aspects of his own theatrical language.

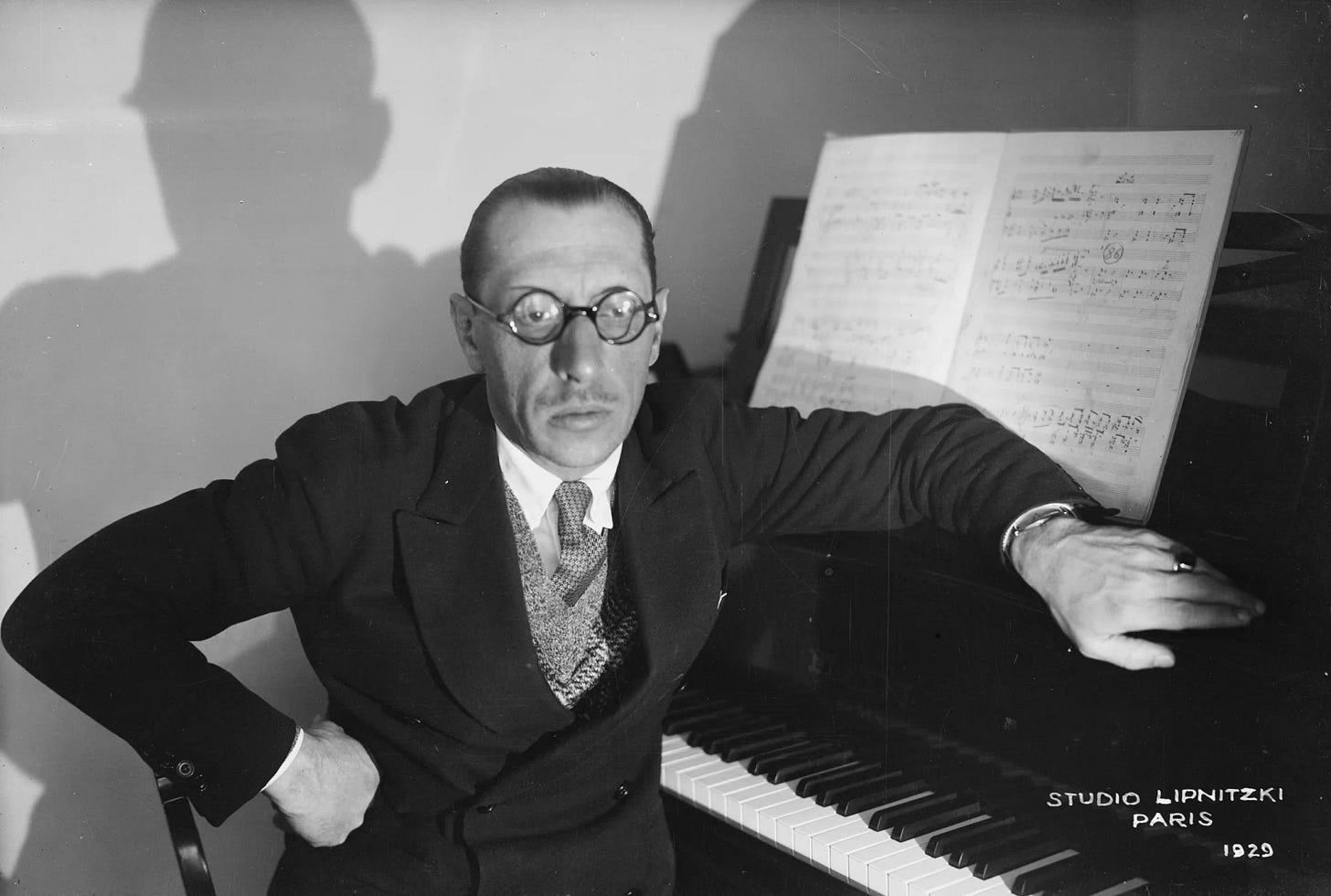

It isn’t just the dissonance of The Rite of Spring that makes it so much fun. It’s the drama in it. Sondheim’s comment cuts to the heart of what makes Stravinsky’s work so revolutionary. While much has been made of its harmonic audacity, perhaps more dazzling still is the way in which The Rite reimagines musical drama itself.

The Rite of Spring emerged from a deceptively simple premise: music for a ballet portraying pagan Russian spring rituals, culminating in the sacrifice of a young woman who must dance herself to death. But Stravinsky’s treatment of this idea upended the language of modern music. From the moment it begins, a lone bassoon keening in its highest register, the piece declares itself as something wholly new.

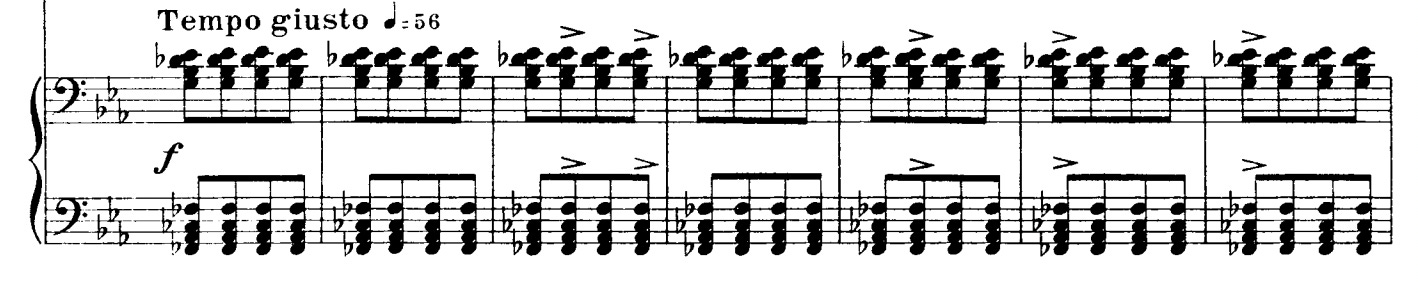

Beneath its surface innovations—the dissonance, the orchestration—lies a deeper transformation: Stravinsky seems to reimagine how music can feel. Rather than merely depicting a ritual, he immerses us in it—and we feel it in our bones. The pounding chords and irregular accents of the famous “Augurs of Spring” don’t so much establish rhythm as generate a physical sensation, as if the earth itself were convulsing. Its driving eighth-note pulse, destabilized by unpredictable stresses, radiates a raw, ritual energy:

We can hear this energy reverberate through Sweeney Todd. Two moments in particular stand out. In “City on Fire,” Sondheim establishes a relentless vamp that echoes the “Augurs” in its pulsing insistence. Where Stravinsky disrupts the pattern with metric shocks, Sondheim achieves a similar instability through text. Vocal lines erupt in uneven bursts—“Rats in the grass and the lunatics yelling in the streets! It’s the end of the world! Yes!”—cutting jaggedly across the regular accompaniment. The clash between voices and vamp creates a tension that feels both chaotic and inevitable:

In “The Contest,” Sondheim adopts a subtler version of the same technique. The harmonic language is gentler, anchored in major chords with sly chromatic twists, but the dramatic effect is no less unsettling. Like the “Augurs”, this music is obsessively fixed around a central chord, its irregular accents refusing to settle. Emphases land unpredictably, throwing us off balance. As we watch Todd and Pirelli’s contest, we cannot help but feel its erratic heartbeat.

The Rite’s revolutionary power also lives in its structure. Stravinsky wields tension through sudden, jarring juxtapositions. Blocks of music collide without warning: no transitions, no soft landings. This fragmentation creates a sense of ritual frenzy, a headlong rush toward catastrophe.

Sondheim adopts this Stravinskian device to striking effect in Sweeney Todd’s final sequence. As London erupts and Todd’s tale nears its climax, the score splinters into a kaleidoscope of musical fragments. The lunatics’ frenzied chorus gives way to Todd and Mrs. Lovett’s eerie “Nothing’s gonna harm you…” fragments, only to plunge back into the chaos moments later. The Beggar Woman’s searching waltz interrupts again, unsettling in its sweetness.

These fractures grow sharper as the climax nears. A tender reprise of “Ah, Miss” and “No Place Like London” gives way to the Beggar Woman’s deranged “Beadle deedle deedle…”—itself breaking apart into jagged underscoring as Todd learns of the Judge’s approach. When the Judge finally appears, “Pretty Women” reemerges, only to dissolve into a death-drenched partial reprise of “My Friends.” As in Stravinsky’s score, musical discontinuity becomes theatrical language. We don’t follow Todd’s descent—we inhabit it, swept into a world where memory, fantasy, and reality crash together with violent force.

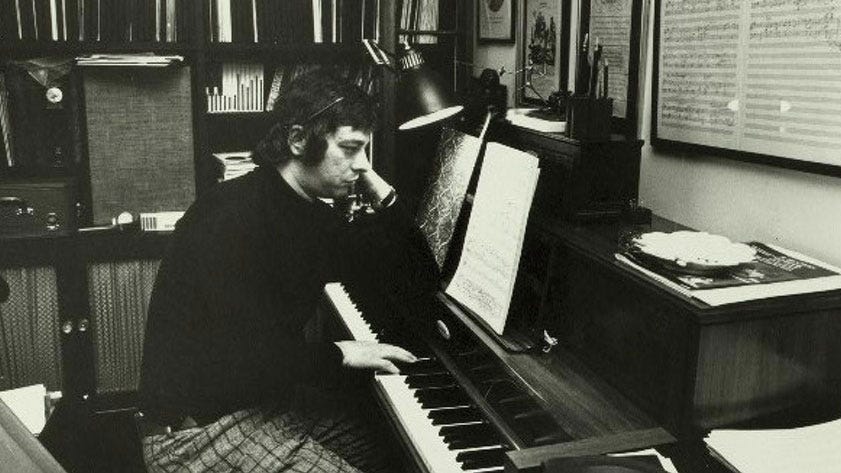

Benjamin Britten composed The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra in 1945, turning an educational commission into something far more ambitious. The premise was, again, straightforward: introduce young listeners to the instruments of the orchestra. Britten chose a stately theme by Henry Purcell—a Rondeau from Abdelazer (1695)—and subjected it to a dazzling sequence of variations, each spotlighting a different section of the ensemble.

But what might have been a dry exercise in orchestration becomes, in Britten’s hands, a theatrical journey. Following a grand, full-orchestra statement of Purcell’s theme—a dignified minor-key dance built on balanced, symmetrical phrases—Britten systematically deconstructs it. Each variation reimagines the melody anew, fusing clarity with invention, tradition with modern flair.

It’s precisely the kind of drama that fascinated Sondheim. When he described Britten as “spiking” traditional materials, he might have been thinking of these variations. The woodwinds render Purcell’s theme light and mercurial, its formal grace softened by darting grace notes. The brass recast it in darker hues: the lower instruments growl out the melody, shot through with ominous chromatic turns. Most striking is the percussion variation, where the theme is stripped to its rhythmic bones: timpani trace its outline in pitch, while surrounding instruments fracture and scatter its remains into a brittle, modernist soundscape.

Nowhere is Britten’s theatrical instinct more exhilarating than in the final fugue. Here, the manipulation of musical time itself becomes a dramatic device. Fragments of Purcell’s theme ricochet through the orchestra at breakneck speed, voices entering in dense, breathless succession. Just as this whirlwind reaches its peak, the original theme reenters—colossal, majestic, utterly unperturbed—in the brass. It’s as if two musical worlds are unfolding at once, their timelines out of sync yet miraculously aligned. The effect is electric. (Click here to listen to the fugue in full. It’s less than three minutes long, and utterly exhilarating.)

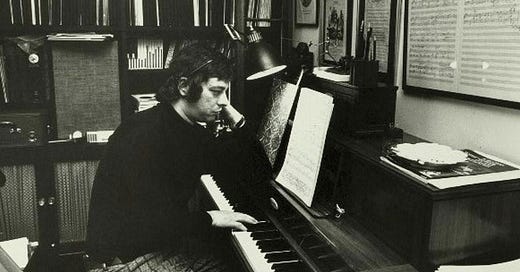

Sondheim, too, manipulates musical time to heighten dramatic tension. In Sweeney Todd’s climactic confrontation, Mrs. Lovett’s panicked explanations about Lucy collide with Todd’s measured responses—and Sondheim makes this temporal disconnect explicit and audible. Todd sings in long, deliberate lines stretched across broad 6/4 and 9/4 measures—music that moves with the dreadful weight of realization—while Mrs. Lovett’s agitated chatter darts unpredictably through shifting meters (6/8, 5/8, 3/8), mirroring her unraveling composure. As she spirals, Todd stays still. His phrases are devastating in their simplicity, punctuated by the repeated invocation of his wife’s name. The disconnect between them—one racing to explain, the other slowing into grim awareness—becomes the engine of the scene’s drama.

We might think too of Sondheim’s temporal counterpoint in “Now/Later/Soon,” in A Little Night Music. The title itself divides time: Fredrik inhabits the impulsive “now,” Anne defers everything to a promised “soon,” and Henrik languishes in a perpetual “later.” Each character’s musical line reflects their temporal fixation. When the three strands are finally woven together, we encounter a kind of textual counterpart to Britten’s fugal miracle: multiple timelines coexisting in a single musical moment.

What Sondheim recognized in both Stravinsky and Britten went beyond technical innovation. He saw how musical structures themselves could generate theatrical power. In Stravinsky’s collision of sonic blocks and Britten’s manipulation of musical time, he found templates for his own dramatic language. But more than that, he saw how these techniques could serve character, story, and emotional truth. When Todd’s psyche fractures into competing musical fragments, or when he and Mrs. Lovett occupy different temporal realms in their final confrontation, we see how concert-hall revolution can become psychological revelation on the musical stage.

This, perhaps, is the most revealing aspect of Sondheim’s relationship with these composers: his instinct for recognizing drama in sound alone. Unlike Sweeney, Sondheim heard music that all of us hear—but in that music, he perceived more than most. He understood that music is drama: every gesture carries consequence, every structure encodes emotion. In his hands, sound and story don’t just complement each other—they reveal themselves to be the same thing.

Thanks for digging into the musical analysis.