On June 30, 1882, Charles J. Guiteau danced his way to the gallows.

This is no metaphor: Guiteau literally danced, reciting verses as he went, turning his own execution into a performance. The condemned man had insisted his shoes be polished, meticulously arranged his hair, and spent his final hours perfecting his death poem, which he had hoped—in vain—would be accompanied by an orchestra. “I am going to the Lordy,” he declared with unsettling cheerfulness, his voice carrying across the scaffold to the crowd below.

That this was the same man who had assassinated President James Garfield seemed, to many observers, almost impossible to reconcile with the near-vaudevillian figure before them. And it is precisely this jarring disconnect that Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman would capture, more than a century later, in “The Ballad of Guiteau.”

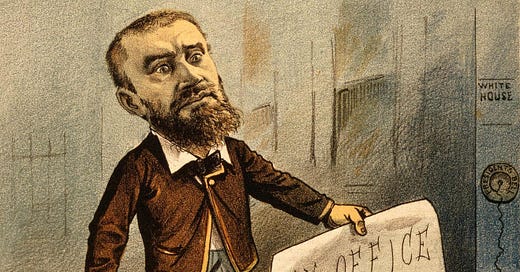

When we first meet Charlie Guiteau in Assassins, he presents himself as America’s eternal optimist, toasting the presidency as “a grand and glorious office” and chiding his fellow outcast Leon Czolgosz for his pessimism. “This is America!” he exclaims, “The Land of Opportunity!” This relentless positivity is, of course, the product of a mind warped by repeated failure and an unshakable belief in his own divine mission. Despite his professional struggles, he saw the burgeoning Republican Party as a ladder to fame and glory, convinced that his work in securing Garfield’s election should have earned him an ambassadorship.

In “Gun Song,” Guiteau’s contribution remained characteristically ebullient, as he cheerfully catalogued a gun’s potential with all the fervor of a revival preacher. Now, as the show nears its climax, we find Guiteau at his own execution, his unflagging optimism about to face its ultimate test. The scene that follows will give us our fullest picture yet of this most peculiar of presidential assassins—a man who, even at the end, remained convinced that his actions were divinely ordained, that his death would be but a stepping stone to greater glory.

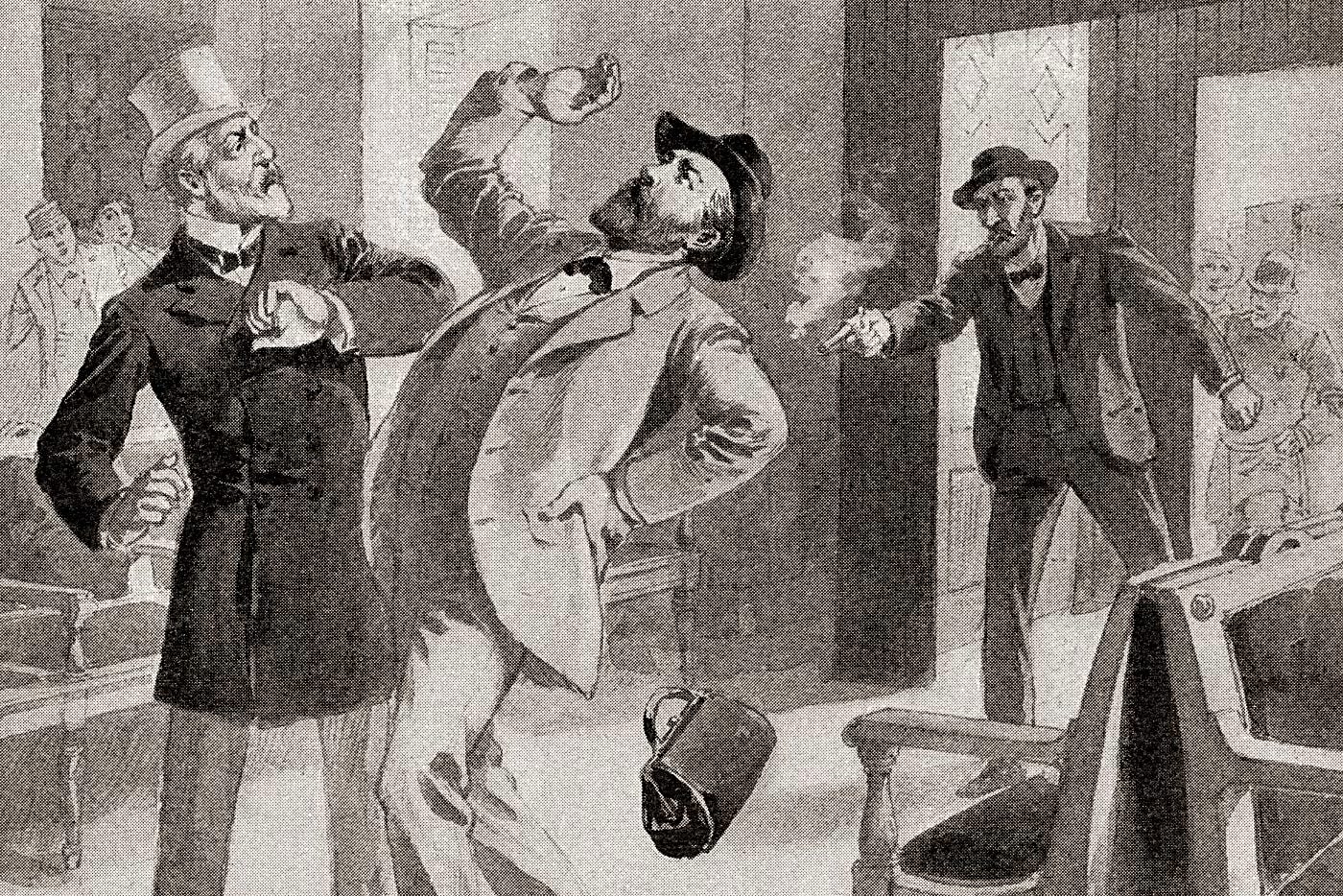

“The Ballad of Guiteau” opens with its protagonist at the foot of the scaffold, his hangman waiting ominously above—positioned, like their historical counterparts, for the grim business of a summer’s day in 1882.

Sondheim and Weidman transform this grim historical tableau into something stranger and more unsettling. While the real Guiteau danced his way to death, his theatrical counterpart performs an even more disturbing spectacle: he ascends the gallows steps in the style of a minstrel show’s cakewalk, a dance form that originated among enslaved people as a satirical imitation of white plantation owners’ formal dances and later became a staple of nineteenth-century American minstrel shows.

By invoking the cakewalk, Sondheim and Weidman draw on its fraught history of subversion turned spectacle, using it to amplify the grotesque theatricality of Guiteau’s final performance. The dance becomes a chilling metaphor for how easily tragedy can be reframed as entertainment (a theme pursued throughout Assassins—see our essay on “How I Saved Roosevelt”), and how delusion can masquerade as confidence.

And in the years since Guiteau’s gallows dance, how often have we seen personal scandal turned into public spectacle? From P.T. Barnum’s strategic exploitation of his own bankruptcies to the media circus of the O.J. Simpson trial, from the carefully curated chaos of reality TV confessionals to viral videos of public breakdowns—each generation seems to find new ways to transform private catastrophe into public performance. We might also bring to mind the carefully choreographed celebrity “Notes app” apologies, the strategic timing of scandal revelations to coincide with album releases, and indeed how the current occupant of that same “grand and glorious office” transformed multiple criminal indictments into campaign victories. One man’s perp walk is another man’s parade.

Charles J. Guiteau’s final moments serve as a disquieting preview of this phenomenon: the condemned man as his own choreographer, staging his final moments for maximum dramatic effect. Assassins’ stage directions call for Guiteau to “dance up and down the steps,” and what we see is a perverse marriage of movement and meaning: each sprightly rise brings him closer to both death and supposed glory. This, perhaps, is a manifestation of the American dream turned horrifically on its head. A man climbs the ladder to success, one careful step at a time—only here, the ladder leads to the hangman’s noose.

The number’s musical structure proves as unsettling as its choreography. Guiteau begins with his own words, the actual poem he wrote and recited on that summer's day: “I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad.” Sondheim’s melody is deceptively simple: a lilting, hymn-like tune that alternates between childlike innocence and disquieting cheer. We feel in this music both the sincerity of Guiteau’s faith and his disturbing detachment from the gravity of his crimes.

When the Balladeer enters, his choice of words is devastatingly precise: “Come all ye Christians, and learn from a sinner.” Where elsewhere in Assassins the Balladeer serves as a more traditional storyteller—whether undermining John Wilkes Booth’s self-mythologizing or recounting Leon Czolgosz’s path through industrial America—here he deliberately mirrors Guiteau’s own religious fervor, delivering a sermon with the assassin himself as the cautionary example.

This marked shift in the Balladeer’s narrative approach reveals Sondheim and Weidman’s sophisticated understanding of how different forms of American storytelling can serve different dramatic purposes. In earlier ballads, the Balladeer maintains a critical distance from his subjects, using folk traditions to frame and often challenge their self-justifications. But with Guiteau, the Balladeer recognizes that he faces an opponent who has already co-opted the language of American optimism and religious conviction. Instead of offering a counter-narrative, he becomes a dark mirror, amplifying Guiteau’s religious certainty to reveal its underlying madness. As this number progresses, we are invited by the Balladeer to witness the unmaking of this self-proclaimed prophet—not through contradiction but through carefully crafted mimicry.

This dismantling begins in earnest as the Balladeer continues: “Bound and determined he’d wind up a winner, Charlie had dreams that he wouldn’t let go.” We might note the double meaning of “bound” here—our protagonist is both resolute and quite literally bound for the gallows. But the Balladeer’s cruelest cut comes when he describes Guiteau’s response to setbacks. “Faced with disaster,” we learn, “his heart would beat faster, his smile would just grow.” This is a psychological portrait that might, in another context, be read as admirable American persistence—here, though, it becomes evidence of dangerous delusion. And the Balladeer delivers these lines with the measured patience of someone who knows exactly where this story ends.

When Guiteau responds, it is as if to confirm the Balladeer’s diagnosis. As the music shifts into an almost vaudevillian jauntiness, Guiteau dances his way from one theological declaration to the next. “Sit on the right side of the Lord,” he urges. He continues: “This is the land of opportunity. He is your lightning, you His sword”—conflating, as he often does, American exceptionalism with divine providence. As Guiteau inches ever closer to his earthly punishment, he thinks only of heavenly promise: “Wait till you see tomorrow / Tomorrow you’ll get your reward!”

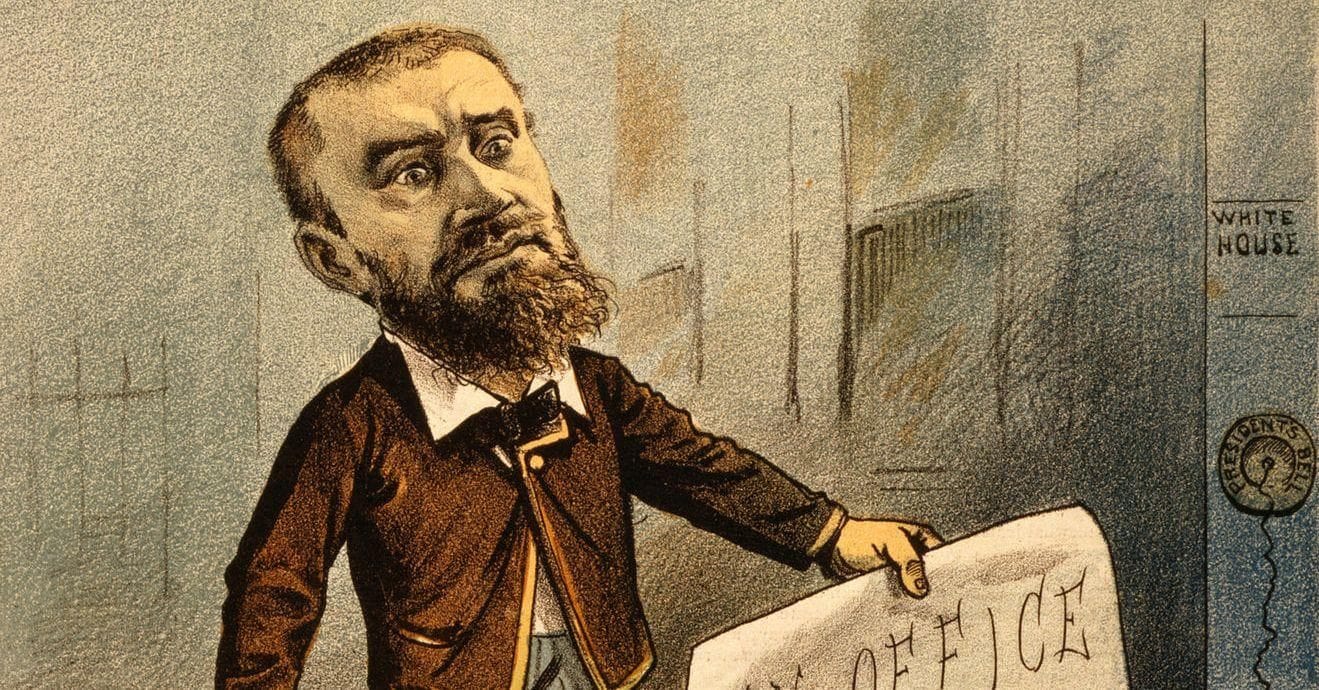

The psychological duel between assassin and Balladeer reaches its apex when we learn of Guiteau’s courtroom performance. “I killed Garfield, I’ll make no denial,” the Balladeer reports him saying, “I was just acting for someone up there.” Here again, Guiteau’s peculiar logic reveals itself: “The Lord’s my employer, and now He’s my lawyer, so do what you dare!”

But the Balladeer’s response is cutting in its simplicity: “Charlie said, ‘Hell, if I am guilty, then God is as well.’ But God was acquitted, and Charlie committed, until he should hang.” In a few short lines, we see the complete dismantling of Guiteau’s theological framework. The assassin who claimed divine mandate finds himself abandoned even by the God he thought had authorized his actions.

Yet even in the face of this theological demolition, Guiteau’s optimism proves grotesquely resilient. Now, in fact, it is the Balladeer who adopts Guiteau’s own optimistic patter, but with devastating irony: “Look on the bright side, not on the sad side, inside the bad side something’s good!”

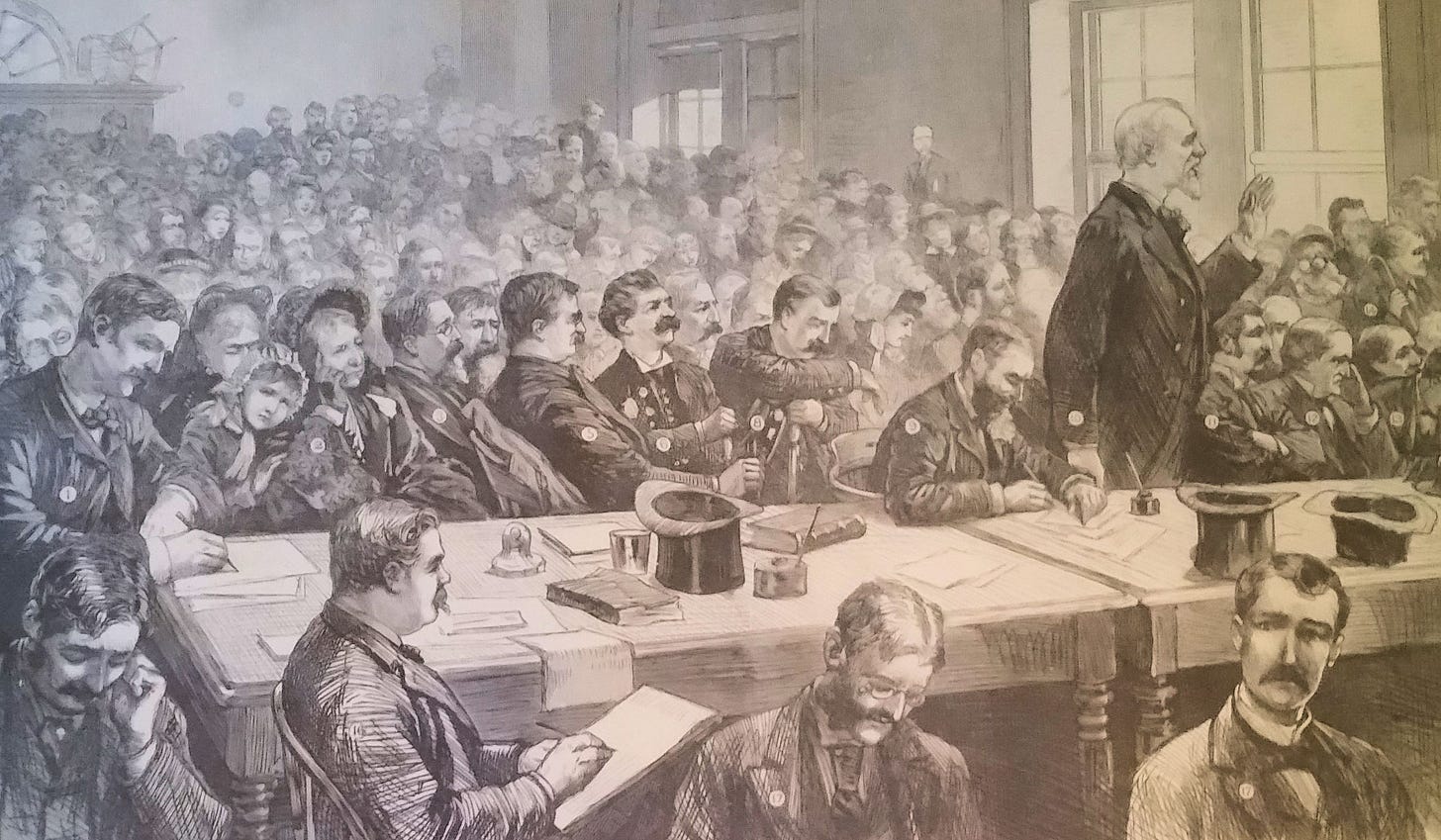

Musically, we might think of this number as a kind of cat-and-mouse game between Guiteau and the Balladeer. Each time Guiteau brings one of his “I am going to the Lordy” passages to a close, he propels the music into new harmonic territory—as if his religious conviction is an unstoppable force that even the Balladeer cannot fully contain. Consider the measures below, for instance. Guiteau’s refrain (highlighted pink) sounds in E major, but his final note pulls us up inexorably into F♯ major, which the Balladeer then maintains throughout the next verse. Note the stage direction: “One step higher than before.” One step higher, in more ways than one…

But Guiteau’s most dramatic musical coup comes with the arrival of each new “Look on the bright side” section. These burst forth in sudden, unexpected keys, completely disrupting the Balladeer’s harmonic logic. It’s as if Guiteau’s delusions repeatedly seize control of the number itself: the Balladeer may dictate the narrative, but he cannot prevent Guiteau from hijacking the musical space with these increasingly manic outbursts. Here, for instance, it seems for all the world as if we are approaching a rock-solid F major chord as the Balladeer tees up Guiteau:

But wait! Guiteau wrong-foots the Balladeer—and therefore us, too. Despite that descending bass motion (above), and despite that seemingly preparatory vocal C (the dominant note of F), we lurch headlong into D major:

Guiteau’s defiance is thereby foregrounded. His ability to wrong-foot us musically reveals a man who still resists the idea of dancing to anyone else’s tune—even as he weaves his own way to the gallows.

As the end of this number approaches, the Balladeer catalogues Guiteau’s life, each of his pronouncements met by the assassin’s eager confirmation: “You’ve been a preacher—” (“Yes, I have!”) “You’ve been an author—” (“Yes, I have!”) “You’ve been a killer—” (“Yes, I have!”). When the Balladeer suggests “You could be an angel,” Guiteau’s earnest response—“Yes, I could!”—is almost heartbreaking. Even now, at the very end, he cannot recognize mockery for what it is. His absolute conviction, his unshakeable belief in his own divine destiny, persists right up to the moment the trap door opens. Consider the final words of this number: “Look on the bright side—trust in tomorrow—and the Lord!” For the Balladeer, these words drip with irony; for Guiteau, they remain a sincere article of faith.

In “The Ballad of Guiteau,” Sondheim and Weidman transform a historical footnote—the peculiar execution of James Garfield’s assassin—into something far more unsettling: a meditation on the darkest extremes of American optimism. Through Guiteau’s final performance, we see how the American dream’s promise of reinvention can curdle into delusion, how religious conviction can become a shield against reality, how even a trip to the gallows can be recast as a step toward glory.

But perhaps most disturbingly, we begin to recognize in Guiteau’s unshakeable optimism something quintessentially American: an insistence that every setback is but a setup for success, that every failure brings us one step closer to glory, that even a hangman’s noose might be a ladder to the stars.