The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

A guide to the film that inspired Act I of Sondheim's Here We Are

A group of well-heeled dinner party guests find themselves perpetually unable to eat. No matter how they try—whether at restaurants, homes, or garden parties—something always intervenes: military maneuvers, a dead restaurateur, or the simple fact that they’re rehearsing for a dinner actually scheduled for the following evening.

This is Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, a film that would go on to win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and, perhaps more surprisingly, serve as source material for Act I of Stephen Sondheim’s final musical fifty years later. As we begin to explore Here We Are, where better to start than with this film?

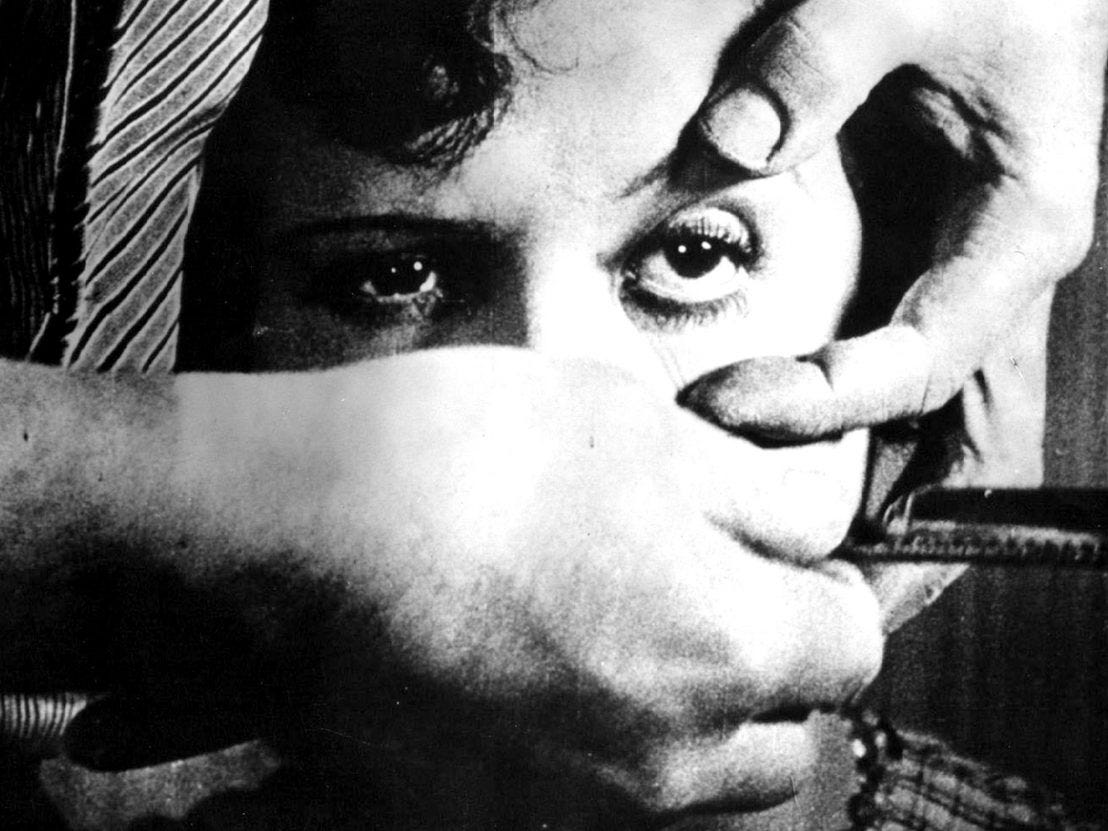

Buñuel’s journey to The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie began over four decades earlier in Paris, where he burst onto the artistic scene with Un Chien Andalou (1929), a collaboration with Salvador Dalí that became the defining film of the surrealist movement. That seventeen-minute silent film, with its notorious opening shot of a razor blade slicing an eye (actually a cow’s eye, but the shock remains), announced a filmmaker determined to assault bourgeois sensibilities. Yet by 1972, Buñuel had developed surrealism into something uniquely his own: less interested in dream-logic shock effects than in using absurdist situations to expose social hypocrisies.

While the early surrealists used techniques like automatic writing and dream imagery to bypass rational thought entirely, Buñuel’s mature style was more subtle. His later films often begin in a world of perfect social realism—expensive restaurants, well-appointed dining rooms, perfectly pressed dinner jackets—before reality starts to unravel at the edges. In The Discreet Charm, this manifests as a series of interrupted meals that become increasingly bizarre, yet the characters maintain their impeccable manners throughout. The surrealism emerges not from obvious dream imagery but from the growing sense that social rituals themselves, when examined closely enough, are already absurd.

This sophisticated form of surrealism was shaped by Buñuel’s unique position as a cultural outsider in multiple societies. After leaving Franco’s Spain, where his early controversial films had made him unwelcome, Buñuel worked in France, Mexico, and the United States. This peripatetic career gave him an outsider’s sharp eye for social pretense in any culture. By the time he made The Discreet Charm in France, he had perfected his ability to observe the upper classes with the detached bemusement of someone who could move freely in their world while never quite belonging to it—and the film’s central characters exemplify the types Buñuel had been studying throughout his career. Let’s meet them:

François and Simone Thévenot

A wealthy couple whose meat company has made them pillars of society (Mrs. Lovett’s wildest dream...). Simone carries herself with an ethereal elegance that barely masks her earthier appetites, while François embodies capitalist self-satisfaction.

Henri and Alice Sénéchal

The hosts of several failed dinner parties. Henri is a more reserved figure than François, while Alice maintains a veneer of perfect hospitality even as chaos erupts around her.

Rafael Acosta

The ambassador from the fictional Republic of Miranda, whose diplomatic immunity provides convenient cover for his cocaine trafficking. Dignified and charming, he pursues a none-too-subtle affair with Simone Thévenot.

Monseigneur Dufour

A bishop who takes a job as a gardener, claiming it’s to stay humble but really because he enjoys the work. His presence highlights the hypocrisy of religious authority cozying up to secular power.

Together, these characters form a sextet of privilege, each representing different facets of bourgeois society: business, politics, religion, and old money. The film’s “plot,” if we can call it that, is deceptively simple: this group of wealthy friends repeatedly try and fail to have dinner together. What begins as a series of mundane interruptions—a scheduling mix-up, a closed restaurant—escalates into increasingly surreal territory. Dreams interrupt reality, then dreams interrupt other dreams, until the distinction between what is “really” happening and what is imagined becomes deliciously unclear.

Yet through it all, our sextet of would-be diners maintains their composure, treating each bizarre new development with the same unflappable politeness they’d show to a minor social faux pas. It’s this tension—between mounting absurdity and rigid social decorum—that makes the film such rich territory for satirical exploration.

The genius of Buñuel’s central metaphor—the perpetually thwarted dinner party—lies in both its universality and its precision. On one level, everyone understands the social anxiety of a dinner party gone wrong; on another, the shared meal represents something deeper about class and civilization itself. These characters’ inability to complete the most basic ritual of cultured society—dining together—exposes the emptiness at the heart of their world. They have the finest clothes, the most beautiful homes, the most impeccable manners, yet they cannot accomplish the simple act of breaking bread together.

Even more tellingly, they never seem particularly hungry. The purpose of their endless attempted dinners isn’t nourishment but performance—the performance of being the sort of people who have elegant dinner parties. It’s exactly the kind of metaphor that would appeal to Sondheim, whose work so often explores the gap between social ritual and genuine human connection, from Bobby’s marriage-phobia in Company to the twisted fairy tale society of Into the Woods.

Indeed, throughout his career, Sondheim had shown a particular fascination with the kind of social performances that Buñuel satirizes in The Discreet Charm. Consider “The Ladies Who Lunch” in Company, where Joanne dissects the hollow rituals of wealthy Manhattan women “planning a brunch, on their own behalf.” Consider too the elaborate social choreography of A Little Night Music’s dinner scene, where Charlotte acidly observes her husband’s infidelity (“Every Day a Little Death”), maintaining perfect decorum while expressing profound despair. Even the cannibalistic meat pies of Sweeney Todd serve as a dark parody of polite society’s consumption habits, with Mrs. Lovett’s customers unknowingly dining on the very upper classes they aspire to join. In each case, as in Buñuel’s film, the act of dining becomes a window into social pretense, class anxiety, and repressed desire.

Sondheim and his collaborators would later structure the first act of Here We Are around three distinct restaurant settings, derived from Buñuel’s film, where social order gradually unravels. As Sondheim himself described their adaptation, “it’s a series of vignettes, really. It’s about a group of people trying to find a place to eat.” The diners of The Discreet Charm discover a restaurant has run out of every beverage—coffee, tea, milk, and even water—yet the maitre d’ maintains his professional demeanor while delivering each successive piece of bad news. In Here We Are, this is realized as Café Everything, whose waiter similarly does his best to be polite as he disappoints the would-be diners:

I apologize profusely, Madam,

But we’re shit out of tea

Today.

Je suis désolé.

In one of the film’s most famous sequences, the diners arrive at a restaurant only to find the owner has died—his body is laid out in the next room while the staff continues to serve customers. Their polite attempts to eat despite the obvious inappropriateness of the situation perfectly captures Buñuel’s mix of the macabre and the mannered. In the hands of Sondheim and his collaborators, this is Bistro à la Mode, which the diners believe will serve “French deconstructivist” cuisine. They are soon disabused of this notion:

LEO, spoken:

Lemme get this straight:

Nothing here is what it seems?

FRENCH WAITRESS, spoken:

Non, non, non, that is passé.

Our new menu is post-déconstructif.

Everything now is what it is.

When Buñuel’s diners finally do get served, the intrusion of military maneuvers shatters their carefully maintained social world—a moment that in Here We Are blossoms into Sondheim’s extraordinary number, “The Soldier’s Dream.” Osteria Zeno, as this restaurant is known in the musical, serves fake food, much to the diners’ chagrin:

SOLDIER:

And I saw that the sheep was stuffed

And the sky was cloth

And the clouds were just paint

And the food was just rubber...

CLAUDIA, spoken:

He’s right! It is rubber!

LEO, spoken:

This isn’t wine, it’s goddamn cherry soda!

RAFFAEL, spoken:

It’s too bad.

I was rather enjoying the brie.

What makes The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie particularly fascinating as source material for theatre is how fluidly it moves between reality and dreams. Characters drift between states of consciousness without warning, dreams nestled within dreams, yet their behavior never wavers. The sequence from which Sondheim’s “The Soldier’s Dream” derives sees the soldier interrupt dinner to recount a dream about meeting his dead cousin for coffee, only for us to discover this entire scene is itself another character’s dream. Through it all, appearances remain immaculate, manners pristine—as if proper etiquette matters more than questioning which reality they currently inhabit.

This interweaving of dreams and social ritual no doubt resonated deeply with Sondheim, whose work so often blurs the line between performance and reality. In Follies, the characters’ memories materialize as young ghosts performing alongside their older selves, while reality and fantasy bleed together during the show’s psychologically complex “Loveland” sequence. The second act of Into the Woods similarly dismantles its fairy tale reality, forcing characters to confront the consequences of their dreams coming true. Even Passion plays with the boundary between waking life and fevered imagination. But where Sondheim typically uses these techniques to reveal his characters’ inner lives, Buñuel’s dreamers remain stubbornly focused on maintaining their external composure—a difference that makes the film particularly ripe for musical theatre adaptation.

This dreamlike quality does allow Buñuel to mine a peculiar vein of humor from his characters’ unflappable composure. When the diners discover they’re performing their meal on a theater stage in front of an audience (another dream sequence), they express embarrassment not at the surreal situation but at having forgotten their lines. When they learn their coffee is actually just hot water colored with ink, they politely decline it as though rejecting an ordinary menu item. The comedy emerges not from broad jokes but from the characters’ steadfast refusal to acknowledge the absurdity of their situations. They are, in effect, trapped in the performance of being upper-class sophisticates, unable to break character even as reality dissolves around them.

Buñuel’s achievement in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie was to create a world where the charade never ends—not in dreams, not in the face of death, not even when reality itself seems to crumble. His characters remain trapped in their endless dinner party, forever pursuing a meal they can never quite consume.

It’s easy to imagine what drew Sondheim to this material: here was a ready-made exploration of ritual, class, and artifice, wrapped in a structure that practically begs to be musicalized. After all, how many times has Sondheim allowed us to glimpse those moments when social masks crack and inner lives peek through? What better theatrical fodder for Act I of his final work than a film about people who can’t abandon their roles, even in their dreams?