A rolling pin pounds relentlessly at an uncooperative pie crust. A kitchen rat scurries for cover. In a grimy London pie shop, one of musical theatre’s most formidable characters is about to make her entrance.

“The Worst Pies in London” serves as more than just a memorable character introduction. It’s a quintessentially Sondheimian piece of craftsmanship, where every note, every rhythmic gesture, and every pause works in service of character development and narrative progression. Christine Baranski sums the song up nicely: it is, she says, “a freakin’ bitch” of a number, but one that, “once you master it, there’s a reason it brings down the house.”

In Christopher Bond’s 1973 play, the corresponding scene (Act I, Scene II) establishes its dark humor through Mrs. Lovett’s forthright commentary on her own terrible cooking and the economic conditions that necessitate it. Here’s how that scene begins:

TODD: Are you all asleep? Some food, here.

Mrs. Lovett enters.

MRS. LOVETT: Are you a ghost?

Todd starts for the door, fearing he has been recognized.

MRS. LOVETT: Hey, don’t go running out the minute you get in. I only took you for a ghost ‘cos you’re the first customer I’ve seen for a fortnight. Sit you down.

Todd sits, warily.

MRS. LOVETT: You’d think we had the plague, the way people avoid this shop. A pie, was it?

Mrs. Lovett’s directness, so quickly established here, carries through to her casual admission about the quality of her pies: “There’s no denying these are the most tasteless pies in London.”

Sondheim, as we know, recognized in this scene its great potential for musical expansion. Mrs. Lovett’s energy—her rapid shifts between topics, her casual relationship with the macabre, her ability to simultaneously tend to her cooking while maintaining a stream of commentary about London’s dire economic situation—practically begged for musical treatment.

As Patti LuPone observes of the resulting number, “It’s so clever. It’s Steve at his best.” And it’s true: in Sondheim’s hands, this number becomes a virtuosic character study that serves multiple dramatic functions simultaneously. It is nothing less than the opening salvo of what would become, in Julia McKenzie’s words, “one of the great parts for women in musical theatre.”

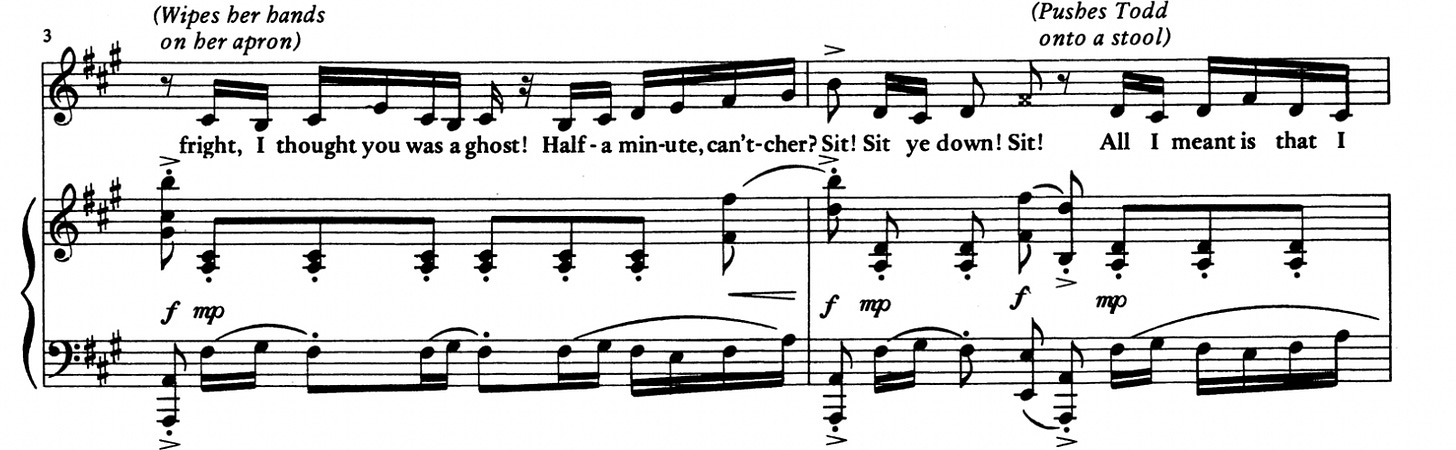

“The Worst Pies in London” is a masterclass in controlled chaos. Sondheim marks the score “Allegretto agitato”—not only lively and spirited, but restless too. Right from the outset, irregular rhythmic patterns mirror Mrs. Lovett’s scattered thought processes. “That song,” Baranski emphasizes, “is not easy musically. It’s not easy lyrically. And all of the physical business has to be syncopated with your lyrics.” This complex integration of music and movement is evident from the very first measures, sharp orchestral accents punctuating Mrs. Lovett’s various activities:

As Lea Salonga observes, “there are a whole lot of built-in reversals and crazy shifts. And I don’t mean vocal, but rather where she goes emotionally. It’s like this woman is the multitasking queen.” And boy, does Sondheim make dramatic virtue of this multitasking. Every rhythmic interruption, every sudden shift in tempo or dynamic, reveals something about both Mrs. Lovett’s character and her desperate circumstances. The score is peppered with performance instructions that support this characterization: “Plucks something off a pie,” “Flicks at something on the counter,” “Pounds the dough.” Each action is precisely coordinated with the musical accompaniment. “It’s laid out for you beautifully on the page,” notes Annaleigh Ashford, “so every lyric tells you what to do next physically.”

“Worst Pies” lays the groundwork for much of what follows in Sweeney Todd. The casual way Mrs. Lovett discusses the dire quality of her pies, her matter-of-fact acceptance of desperate measures in desperate times, even her tendency to chatter on while performing gruesome tasks—all of these elements will become crucial as the show proceeds.

Dramatically, the number unfolds through masterfully paced incremental revelation. Mrs. Lovett begins with the startlingly mundane: her customer’s unexpected arrival, her shop’s lack of trade, the questionable quality of her pies. But notice how the scope of her commentary steadily widens. First come the local, immediate observations (“These are probably the worst pies in London”), then the economic realities that have led to her situation (“with the price of meat what it is”), before finally expanding to broader social commentary about the desperate state of London itself (“Men’d think it was a treat / Finding poor animals / Wot are dying in the street”).

This progression is masterfully handled through those “built-in reversals and crazy shifts” that Salonga mentioned. Take the disturbing story of Mrs. Mooney’s pie shop, for instance, where “lately, all her neighbors’ cats have disappeared.” It’s brilliantly witty, of course—but it’s also crucial in revealing both Mrs. Lovett’s keen awareness of her competition and her seemingly paradoxical moral stance. “Wouldn’t do in my shop,” she declares, even as she acknowledges the “enterprise” of such an approach. Sutton Foster captures this complexity when she observes that “there’s so much that she’s establishing... it’s delightful, terrifying, and I’m still in constant discovery with it.”

Incidentally, in the Bond play, there is no “popping pussies into pies.” Here is how Bond’s Mrs. Lovett tells Todd of her competition:

The other day, Tuesday it was, I was walking down Cheapside, and I saw a crowd of people looking in a pie shop window. Well, I thought, I’d better have a look an’ all. And there in the window, pretty as a picture, was a roasted cat all garnished round with little mice tied up to look like sausages. Beautiful it was.

Sondheim’s number concludes with what might appear a simple lament—“A woman alone / With limited wind / And the worst pies in London!”—but by now these words carry far more weight than they would have done just a few minutes earlier. Through her seemingly scattered commentary, Mrs. Lovett has revealed not just her circumstances, but an entire moral worldview. As Baranski notes, “You have to earn the final act of Sweeney, which turns really dark and tragic.” That process begins here for anyone portraying Mrs. Lovett, as she draws an unequivocal line between economic desperation and increasingly questionable moral choices.

Later, of course, a memorably grizzly solution to this pie shop’s meat shortage will be proposed—but here, the dramatic foundations are already being laid. Mrs. Lovett’s casual acceptance of her competitor’s “enterprise,” her matter-of-fact acknowledgment of people eating animals found dead in the street… These are the first steps on a path that leads inexorably to human flesh in bakehouse ovens.

Much of “The Worst Pies in London” skitters and scurries like Mrs. Lovett’s resident vermin, Sondheim’s accompanimental figures and fragmentary vocal lines matching her constant bustle. But there are moments when this nervous energy gives way to something more expansive. These broader phrases, often settling into something distinctly waltz-like, allow both character and audience a moment to breathe:

These musical shifts mirror Mrs. Lovett’s own duality: the chattering shopkeeper versus the clear-eyed survivor. “If comedy is good, it’s honest,” notes Annaleigh Ashford, and these moments of musical spaciousness allow us to see the brutal honesty beneath Mrs. Lovett’s seemingly scattered surface. That these passages are waltz-like is particularly telling: they prefigure not only the ghoulish dance of “A Little Priest,” but also, much later, her final bakehouse totentanz.

The theatrical demands of “The Worst Pies in London” are as complex as Mrs. Lovett herself. “That role takes you everywhere from almost-vaudeville comedy to grand opera,” observes Baranski. “But I was careful not to lean too much into her comedic side. You have to be invested enough in the seriousness of the piece to be genuinely horrified and stunned and shaken by the violence.” Helena Bonham Carter notes that for the film version, “Tim [Burton] is not into broad comedy. Everything has to be held back... It is innately funny, but we didn’t play it for laughs.” And Bryonha Marie is similarly keen to emphasize the character’s darker qualities: “She’s really dangerous. Angela Lansbury is incredible—I think she’s cute as a button, though. I wasn’t super scared of her. I was much more scared of Sweeney in that production.”

This push-and-pull between comedy and menace extends to the number’s demanding physical business. “For me, it’s the hardest moment in the show,” admits Sutton Foster. “I feel like that’s really when Mrs. Lovett becomes unhinged or unleashed.” The physical comedy must serve the character rather than distract from her, a challenge captured by Annaleigh Ashford’s observation that she “had to make sure that Mrs. Lovett really was grounded in honesty, even though her physicality was sort of wild and zany.”

Perhaps what’s most remarkable about this number is how it operates simultaneously as comedy routine, character study, and social commentary. Through Mrs. Lovett’s apparently scattered observations, Sondheim and Wheeler paint a vivid picture of Victorian London’s economic desperation. We laugh, but we also see exactly how someone might be driven to contemplate the unthinkable. “Given the time period in which she is existing,” Lea Salonga reflects, “it’s like, ‘Of course she would figure out a way to off people and make money off of that.’ It’s not even, ‘But how can you kill people?’ It’s simple: you’re desperate and you need money and you’ll do anything.”

“I think you have to, first of all, make a big choice,” Julia McKenzie observes, “as to whether you think she’s just thoroughly evil or whether you think she was coping with those terrible Victorian times when everyone was just fighting to live, really.” Christine Baranski develops this idea in a particularly compelling direction:

There was a book I read for research called London Labour and the London Poor, which is about the underclass in Victorian England. If you read about it, you know it was a grisly life—almost, at times, bestial. So there was an animalistic quality to her.

This context helps explain not just Mrs. Lovett’s actions, but Sondheim’s genius in making her story simultaneously specific and universal. While “Worst Pies” is firmly rooted in the grim realities of Victorian London, its portrait of how economic desperation can erode moral boundaries resonates far beyond its historical setting. Through this deceptively simple scene of a woman serving (or failing to serve) a pie to her customer, Sondheim and Wheeler explore timeless questions about survival, morality, and the choices people make when pushed to their limits.

Particularly chilling here is that these themes are presented not through grand philosophical statements, but through the mundane details of daily commerce. When Mrs. Lovett remarks that “times is hard,” she’s not just making idle conversation—she’s offering a justification for whatever might follow. Sondheim makes us complicit in this moral calculation, inviting us to laugh at her predicament even as we begin to understand the horrifying logic that will eventually lead to murder.

“The Worst Pies in London” introduces us not only to Mrs. Lovett, but to the moral universe of Sweeney Todd. We see that the line between comedy and horror can be terrifyingly thin. We see too that the most frightening villains are often seemingly ordinary people who, pressed by necessity, might rationalize any action in the name of survival.

Sweeney Todd remains such an enduringly powerful work in part because it understands that true horror lies not only in grand acts of evil, but in the small compromises we make in the name of necessity, the gradual ways in which desperate circumstances can normalize the unthinkable. “Times is hard,” Mrs. Lovett tells us—and in those three short words lies the seed of every horror that follows.

Actor commentary in this piece is drawn from a terrific oral history of Mrs. Lovett published in 2024 by The Washington Post, which is well worth a read.

OMG. What a terrific piece! Thank you thank you. “Times is hard” indeed and understanding human nature at this moment and the critical choices we are in the process of making as individuals and as a society is as momentous as it gets. Bravo Mrs Lovett and hats off once again to Sondheim and to you Yassi Noubahar for this reminder not only of his genius but of our times and our choices.♥️

It’s so crazy how relatable Lovett remains to the average woman