What The Eye Arranges

Exploring "Beautiful" (Sunday in the Park with George)

Pretty isn’t beautiful, Mother.

Pretty is what changes.

What the eye arranges

Is what is beautiful.

This lyric, from Sunday in the Park with George’s “Beautiful,” is among Sondheim’s most adored—and with good reason. And what Sondheim wrote about these words, decades later (in Look, I Made a Hat), is equally moving:

It’s still a favorite lyric of mine, and I think I know what it means.

The humility in Sondheim’s reflection—that tentative “I think”—speaks volumes about the nature of the truth he captured in these lines. It’s a truth that is almost impossible to articulate, but which reveals itself anew—if only for a fleeting, precious moment—each time you encounter this number.

If you are lucky enough to witness a truly great performance of “Beautiful,” it moves you quite literally beyond words. A few days ago, at London’s Alexandra Palace, Jenna Russell and Jack Wolfe delivered one such performance.

“Beautiful” features as part of Sondheim on Sondheim, the musical revue conceived by James Lapine and first produced in 2010. London’s all-star cast—Clive Rowe, Josefina Gabrielle, Jak Malone, Georgina Onuorah, Lucca Chadwick-Patel, Scarlett Strallen, Jack Wolfe, and Jenna Russell—worked all manner of magic on that stage. If this were a review site, I would try to capture the evening as a whole. I would giddily catalogue events as they unfolded, lavish praise upon all eight performers (who each in their turn took my breath away), and extol the many virtues of musical director Alex Parker, director Paul Foster, and choreographer Joanna Goodwin.

Now, this may not be a review site, but I feel moved to respond to just how good this Sondheim on Sondheim was. There are so many moments I’m excited to revisit in future pieces of writing—but I’d like to start with “Beautiful.”

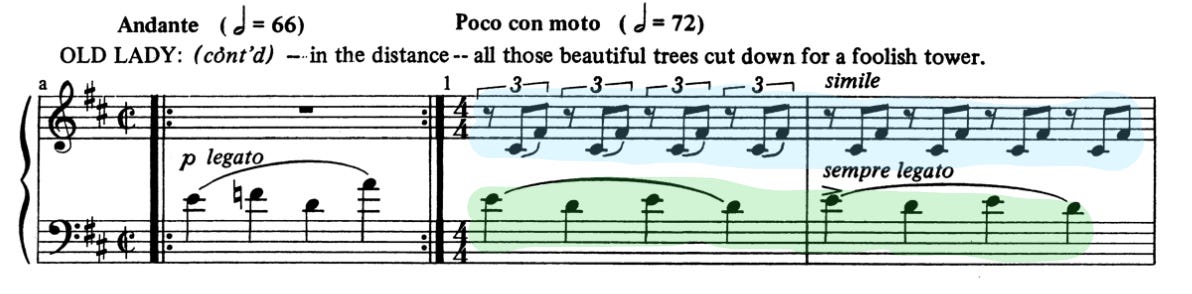

Jenna Russell sits downstage on a simple wooden chair; Jack Wolfe kneels beside her (see above). They are mother and son, in that small, suburban park, looking out at the view. And Sondheim works his magic before either person sings. Look at the undulating figure we hear just before the first words of this number:

What do we see here? What does your eye arrange? Is it one repeating pattern, or two intertwined? Of course, it can be (and is) both. Let’s first consider the idea that these are two interlocking patterns. On the lower staff we see descending whole steps, like sighs, marking time on each musical beat. On the upper staff it’s all rising fourths: quicker, bouncing off each beat, less tethered… One pattern feels more earthbound; the other seems to float.

A musical mother and son?

Now let’s take this accompanimental figure as a single musical object (lest we be accused, by George himself, of “seeing all the parts and none of the whole”). What can we say about it? Well, it is made up of just four notes: the first, second, third, and seventh degrees of the (major) scale. Do, re, mi, and ti (D, E, F♯, and C♯)—with ti in this case sounding lowest. What we hear, then, is four consecutive notes of the scale—which we can call a tetrachord. (Think of a Tetris game piece, always composed of four square blocks). If these four notes were played simultaneously, they would form a cluster—but Sondheim spreads them out across his temporal canvas. I need hardly labor the painterly metaphor further when discussing this show…

What this initial accompaniment represents, then, is stasis and motion in equal measure—or, to use the language of this number, “stillness” which is nonetheless “changing.” And when George’s mother speaks for the first time, she lends credence to the claim that the falling accompanimental figure relates in some way to her. Her first words are musical sighs too:

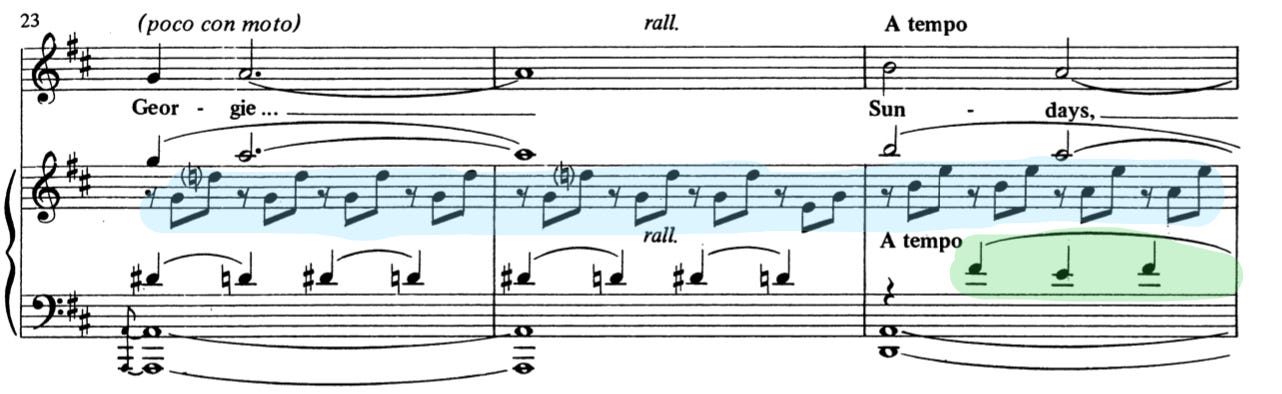

Almost immediately, George’s mother introduces a note that does not belong in the key: B♯. In doing so, she disrupts the diatonic equilibrium of the opening measures—she “spoils” the musical landscape, as if to underscore the point she will soon make. “I see towers where there were trees…” Look at the choice of notes for “it keeps” too: a descending fourth, the second note of which is F♯. Now look again at the upper voice of the accompaniment: repeated ascending fourths, the second note of which is F♯. Order, design, tension, composition, balance…

Under “towers” itself, the upper voice of the accompaniment changes for the first time. Perhaps importantly, it rises, while the lower “mother” voice remains where it is. Note that the lower voice remains constant even when its D♮ rubs up against the upper voice’s D♯. It finally changes, though, under the word “solitude,” where its whole step becomes a half step:

In these measures, it is as if that “mother” voice is now echoing her first word, which was also a falling half step: changing, changing, changing, changing…

George’s mother reaches her melodic highpoint on “Sundays,” and the upper accompanimental voice has continued to rise with her, a son shadowing his mother. Now, look what happens to the lower accompanimental voice when we reach that climax:

Here, the two-note pattern is extended; it still starts with falling whole steps, but Sondheim spins it out into a countermelody (above, in green). The pattern thereby gains musical authority within the texture, just as George’s mother becomes more emphatic, more assured. Pay attention to the shape of that countermelody…

When George speaks, it is to his mother—and he uses “her” countermelody as his melody. He is not talking down to her—not one bit. George offers his perspective, but musically he does his best to speak his mother’s language. This is true lyrically too:

All trees, all towers beautiful.

That tower beautiful, Mother, see?

A perfect tree.

What an act of love.

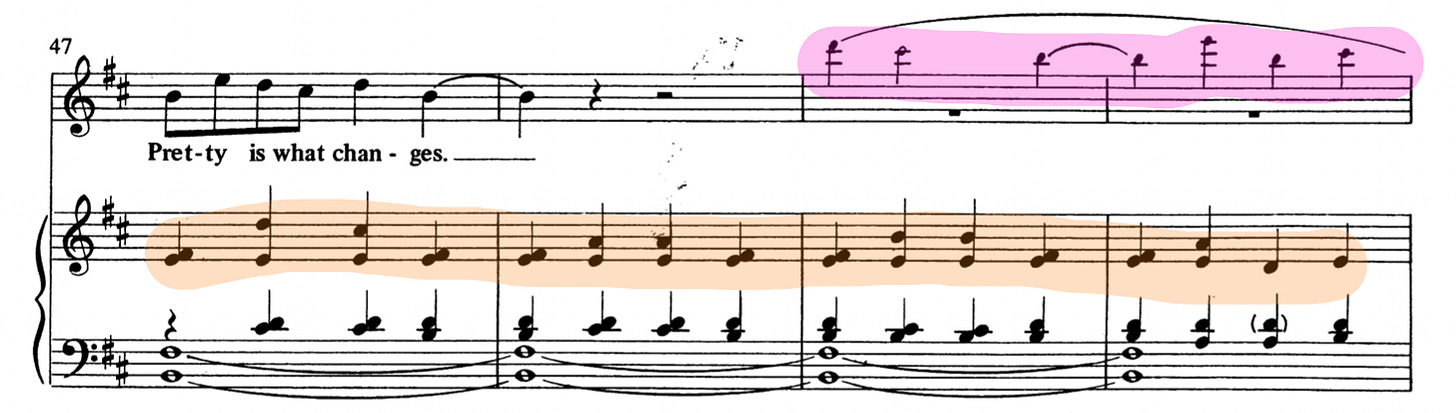

And then we reach those famous lines. The quatrain that begins with “Pretty isn’t beautiful” stands apart from the rest of this number, musically speaking. And Sondheim’s accompanimental choices are, I think, a big factor in why we find this particular passage so moving. Look at what we hear beneath the melody:

Yes, that is George’s painting motif. In Sunday, we grow accustomed to this figure in its pointillistic guise—as the figure, in fact, that begins “Color and Light”:

Here, though, its rough edges are smoothed out—its intervals are larger, what was once chromatic is now diatonic, and it sits comfortably within its harmonic context. George tells his mother that “pretty is what changes”—and Sondheim proves that very point.

As the painting motif continues to churn below George’s words, Sondheim mixes in another ingredient. The phrase in pink you see above started life as something akin to an absent-minded hum. Here is its first appearance, in “Color and Light”:

To use this figure in “Beautiful,” under these particular words, is a stroke of genius. It is like George is speaking not only with his voice, but also with his soul. In Sunday, we will soon hear that phrase again—in the finale of Act I, just before we hear of those “people strolling through the trees.” Those same trees that George’s mother misses so terribly. Those same trees that her son will preserve forever in his painting.

As we reenter the main soundworld of “Beautiful,” George soothes his mother as her lamentation continues. It is worth noting that two of George’s most powerful lines—“I’ll draw us now before we fade” and “You watch while I revise the world”—are again borne out of that earlier countermelody derived from his mother. After the final climax of “Sundays” (the only word in “Beautiful” sung by both characters in unison), the number begins to settle and subside.

What do we hear as this number draws to a close? Two things. First, words of love from a mother to her son:

You make it beautiful.

Second, a gut-punch. The final, spoken line of this number that exposes an uncomfortable truth: George’s words have had little, if any, effect on his mother.

Oh, Georgie, how I long for the old view.

In Sondheim on Sondheim, the minutes that follow “Beautiful” are truly devastating. Sondheim, projected behind the performers, begins to speak. “I had a lot of trouble with my mother,” he says—which is putting it mildly. At Alexandra Palace, Jack and Jenna face upstage, hand in hand, as Sondheim talks of his parents’ relationship. We see our performers, so recently George and his mother, in silhouette. And as Sondheim describes his father leaving his mother, Jack leaves the stage. Jenna is left alone, hand still outstretched.

It is not long before we hear Sondheim describe the letter his own mother wrote to him, the night before she was to have open heart surgery. She had this particular letter hand-delivered. It read, in part, “The only regret I have in life is giving you birth.”

Even if you’ve never seen Sondheim on Sondheim, you can probably guess the number that follows. It contains words that, in this context, are not soon forgotten:

Careful the things you say.

Children will listen.