Give Another Number To Me: Michael Bennett’s Kinetic Contributions to the Prince-Sondheim Canon

A guest essay by Natalie Guevara

Natalie Guevara is a writer, marketing executive, and creative consultant who lives between Miami and the Dominican Republic. She publishes a Substack called Mise-En-Scène. Currently, she is developing a comprehensive legacy project exploring Michael Bennett’s impact on American musical theatre. Her work will examine how Bennett's dynamic vision and collaborative spirit continue to reverberate through contemporary Broadway entertainment.

With great enthusiasm, she invites Bennett collaborators, theatre historians, dance scholars, and passionate admirers to connect with her if they're interested in contributing their perspectives to this celebration of his artistry—with more details coming soon: natalie.guevara@gmail.com

“What [Michael] Bennett had is a sense of the tradition of the musical theatre combined with a dramatic imagination, that is to say, a way to use the tradition of the musical theatre. I’ve spoken to people who know a lot more about dance than I do who say that his vocabulary was very limited. But within that vocabulary, which was very specifically oriented in musical comedy tradition, he was very imaginative, particularly about how to use stage space. The only person I know that had it more than he was Jerry Robbins, and it’s not coincidental that Michael always looked up to Jerry with great admiration.”

— Stephen Sondheim remembers director-choreographer Michael Bennett1 in an interview with author and Bennett biographer Ken Mandelbaum

Thirty-eight years ago this month, Broadway lost one of its most incandescent visionaries. Michael Bennett, the award-winning director-choreographer behind A Chorus Line (1975) and Dreamgirls (1981), died on July 2, 1987, at just 44 years old, another casualty of the AIDS plague that devastated the theatre community. Yet his innovative approach to making shows move, in every sense of the word, continues to pulse through the theatre entertainment we experience today.

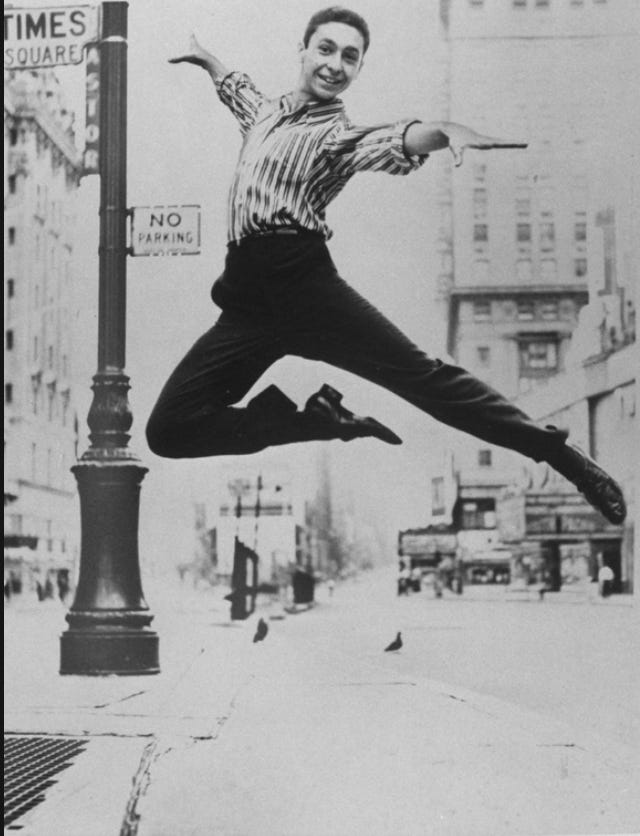

Michael Bennett transformed himself from a hard-hoofin’ chorus kid in the late 1950s and '60s into a Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning force by the mid-'70s and '80s.

But before Bennett struck out on his own—before he began doctoring and directing shows for the likes of Neil Simon, and eventually conceiving and producing his own work alongside tight-knit collaborators such as his professional partner and best friend Bob Avian, the trailblazing theatrical producer Joseph Papp, the inventive scenic designer Robin Wagner, Shubert Organization president Bernie Jacobs, and entertainment impresario David Geffen—he sharpened his point of view through key collaborations with groundbreaking contemporaries: Harold Prince and Stephen Sondheim, and by extension the writers George Furth and James Goldman.

I Want To Make Things That Count

Let me take you to late September 1987. It’s been almost three months since Bennett’s death. His memorial service was held inside the Shubert Theatre in midtown Manhattan, the Broadway home of A Chorus Line, where the show was still playing to sold-out crowds.

In a melancholy coincidence, exactly four years earlier on that same date, September 29, 1983, Bennett, his Chorus Line collaborators, and 300-plus dancers—champagne-spangled alumni from every U.S., international, and touring production of the Broadway smash—were taking bows on this very stage at a dazzling gala performance celebrating the show’s 3,389th performance, a remarkable milestone that marked its dethroning of Grease as the longest-running show on Broadway.

Now, four years later, the mood was solemn. The Shubert was full to the rafters, but this time with an audience of Bennett’s stoic loved ones: his friends and family, his devoted dancers, and his many creative collaborators and admirers, a veritable who’s who of American theatre royalty. A bespectacled John Breglio, then Bennett’s lawyer and today a Broadway producer and the executor of Bennett’s estate, stepped to the podium.

In delivering a tribute to Bennett, Breglio offered a vivid memory of a quiet moment together among colleagues and friends. “It was a couple of years ago. Michael asked me to come up to his apartment to discuss some business. When I got there, he said that he wanted to play for me an advance copy of the cast album for Sunday in the Park with George,” Breglio reminisced. “As we listened, he played just one song. He stood in the corner of the apartment, looked out the window, his back towards me. When he turned around, there were tears coming down his face. It was the only time I’d ever seen Michael cry.” Breglio closed his eulogy by announcing a special guest: “Ladies and gentlemen, Stephen Sondheim, who will play that song from Sunday in the Park with George.”

A visibly stricken Sondheim walked across the Shubert stage to sit at a piano. He began playing and singing familiar bars from Sunday, a production Bennett supported and offered notes on while it was in early previews2. It was a rare public performance by Sondheim.

Sondheim Sings “Move On” at Michael Bennett’s Memorial:3

The song Sondheim performed, “Move On,” was Michael Bennett’s favorite. It’s a song about wrestling with artistic insecurity, and continuing to create in spite of it.

As Sondheim reached the song’s ending, he plaintively sang its last lines:

Anything you do

Let it come from you

Then it will be new

Give us more to see

Sondheim inhaled. His voice cracked: “Goodbye, Michael.”

Although we can't see the audience members in this clip, we pick up on enough atmospheric cues to perceive that they were shaken. They applauded with overwhelming feeling as Sondheim stood from the piano, picked up his sheet music, and walked offstage into darkness. Even now, almost four decades on, we, the second-hand viewers, share in their collective grief.

Michael Bennett would no longer be able to give us more to see.

What Would We Do Without You?

“He showed us deep truths about ourselves. He made us more aware of being alive, to use the words of one of his great collaborators. The Greeks, I think, call this a catharsis. Michael called it a Broadway musical.”

— Frank DiFilia honors his late brother Michael Bennett at the 1987 memorial tribute4

Those who knew and worked with Bennett remember him as a man with razor-sharp showbiz instincts, a fiercely inclusive spirit, a generous supporter of his fellow theatremakers, and a fabulous dancer with a quicksilver mind to match his fleet-footed confidence. He valued truthful emotional expression above overwrought intellectual pretension, a sensibility he channeled into crafting moments that stopped shows cold and roused audiences to their feet.

Broadway Baby

Born Michael Bennett DiFiglia in Buffalo, New York on April 8, 1943, he began dancing at the age of three. His earliest outlets for performance included his local dance studio, family weddings, and school productions that he conceived, directed, choreographed, and produced himself. At 17 years old, he dropped out of high school to join the 1960 European tour of West Side Story, on which he first crossed paths with Avian.

Once Bennett was back stateside, he danced in the choruses of Broadway shows and on TV, including for The Ed Sullivan Show and as a featured dancer on Hullabaloo, a groovy ‘60s foil to the more staid American Bandstand. It was on Hullabaloo where he met Donna McKechnie, who would soon become his muse and favorite interpreter (the Chita Rivera to his Robbins, or the Gwen Verdon to his Fosse, if you will5). In Ken Mandelbaum’s 1989 biography of Bennett, McKechnie said: “He saw something in my ability to take his work and go with it… [...] Talent excited him, and it was more exciting for him to see his work and make somebody else look good and be the star, than for him to go out there and shine.”6

He also cut his teeth choreographing summer stock, a rite of passage for many musical theatre choreographers who ascended during the era (including Bennett’s friend and contemporary Tommy Tune), as well as mid-’60s Broadway shows like A Joyful Noise and Henry, Sweet Henry. While these shows had short runs, they generated good notices for his inventive dances before the 1968 hit Promises, Promises put the boy from Buffalo on the map. Featuring a contemporary pop score by Burt Bacharach and Hal David and an irresistible Act One closer in “Turkey Lurkey Time” (choreographed by Bennett and Avian, with McKechnie leading the ensemble), the show established his reputation as a new kind of choreographer.

Success is Swell and Success is Sweet

“I mean, Michael Bennett was—it!” said Thommie Walsh, the late director-choreographer who launched his career under Bennett’s direction on several milestone productions. “All I wanted to do was be in a Michael Bennett show.”7 He’d get his first shot in 1973 when Bennett brought him aboard Seesaw (1973), and later as the original Bobby, a character drawn with shades of Bennett himself, in A Chorus Line (“I thought about killing myself, but then I realized to commit suicide in Buffalo is redundant”).

Self-possessed and driven, Bennett knew he was destined for greatness. Those who met him early in his career—Avian, McKechnie, and his first and only manager Jack Lenny—all described being similarly taken aback by his proclamation that he didn’t just want to be a choreographer; he wanted to be the next Robbins.8 On his ambitions, Bennett mused: “I just said, ‘I can do it,’ and I said it loud enough so that somebody heard me.”9

Somebody heard him, alright. Despite being reductively labeled as a “disco choreographer” by theatre circles after the success of Promises, Promises, Bennett, never one to be underestimated, showed his range on his next project, Coco (1969), the bio-musical starring Katharine Hepburn as Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel and featuring talented Broadway gypsies (not to mention future director-choreographers) Ann Reinking and Graciela Daniele as her elegant models. They walked and posed chicly in Busby Berkeley-esque formations staged on Cecil Beaton’s descending mirrored staircase and turntable revolves to great cinematic effect.

“Bennett and Avian achieved a seamless collaboration between the set, costumes, music, lyrics, and dance, all at the service of telling a story and, in the case of Coco, showing off a star of the caliber of Hepburn,” wrote musical theatre choreographer and dance scholar Liza Gennaro in her 2021 book Making Broadway Dance. “There is a high level of craft at work here, but there is also a degree of wizardry. An intangible instinct and visual sense that some choreographers have and that makes their work astonishing and crystalline in its ability to convey ideas through movement.”10

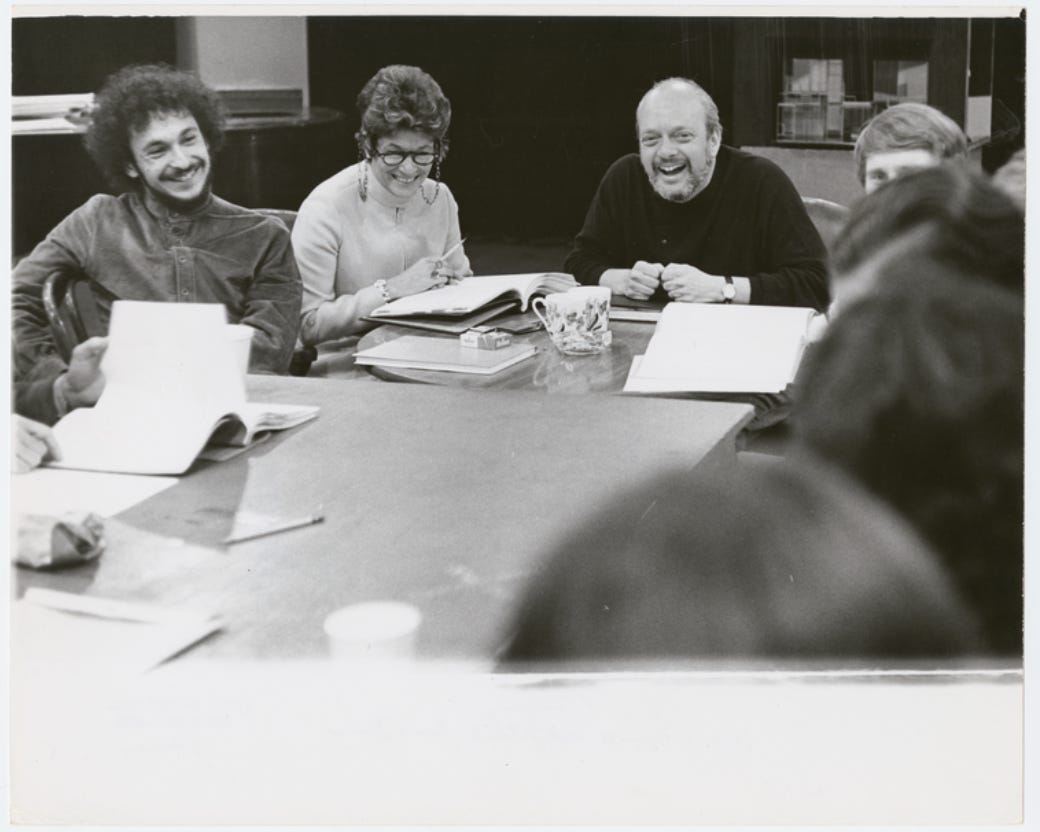

It was precisely this unexpected dynamism in Coco—an otherwise lackluster show, despite the involvement of André Previn and Alan Jay Lerner—that made Hal Prince sit up and take notice. The ambitious boy genius producer-turned-visionary director decided to bring Bennett and Avian into the fold on his next project: a new musical comedy about a thirtysomething bachelor, Robert (nicknamed Bobby), who is bewildered by the companionship and alienation he encounters while navigating his social scene of married couples and weary girlfriends in cosmopolitan, claustrophobic, cacophonous Manhattan.

“Phone rings, door chimes…”

In Comes Company

“I went to things in the character to determine the style of movement. But that show was about New York City and I know what the temper of the life is in New York City.”

— Michael Bennett on why Company (1970) proved an exception to his typically exhaustive research process11

Prince, Stephen Sondheim, and George Furth were among the most exciting people working on Broadway as the transitional, combustible ‘60s gave way to the bold, urbane ‘70s.

Much like the New Hollywood auteurs of the era (Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg), this Broadway new wave understood what the rules for a stage musical were backwards and forwards—and proceeded to effectively break them. They had developed their craft during Broadway’s Golden Age, learning the ropes from stalwarts like George Abbott, Prince’s first big boss, and Oscar Hammerstein II, Sondheim’s mentor and surrogate father.

Now approaching their creative prime, Prince, Sondheim, and their collaborators asserted new perspectives in a disillusioned, corrupted Vietnam-era America. They were determined to challenge musical theatre conventions, to create something that didn't just entertain but explored and even confronted the world they were living in.

It was in this crucible of innovation, working with these kindred talents, that Michael Bennett would hone the visceral sensibilities and musical verité that would propel Broadway into a new era.

Despite being a decade-plus younger than the rest of the creative team on Company, Bennett had demonstrated in his previous work a remarkable ability to choreograph concepts, not just steps, all while capturing the times he was living in with sensitivity and finesse.

Baayork Lee, a fellow chorus kid who had studied alongside Bennett at Syvilla Fort’s influential dance studio12 and later danced in four of Bennett’s choruses before memorably originating the role of “four-foot ten” Connie Wong in A Chorus Line, noted his gift for extracting inspiration from the zeitgeist and making it dance: “Michael took what was happening and put it on the stage.”13

In that same vein, Prince knew that Company was an opportunity to say something that spoke directly to modern audiences, and specifically to his sleek, sophisticated peers. He had plenty of experience shaping unconventional, dangerous material like Cabaret (1966). But Company presented a new animal for Bennett and Avian—their first encounter with “the concept musical.”

Parallel Lines Who Meet

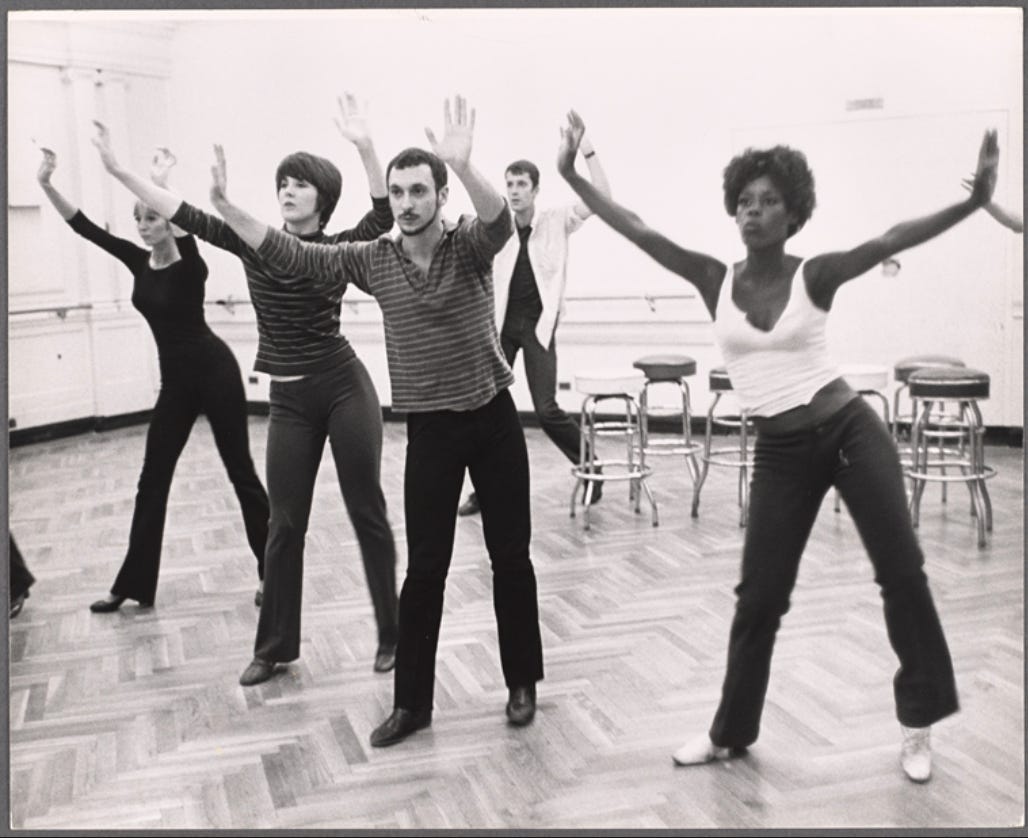

Company was an assignment Bennett and Avian took on with their characteristic chutzpah, marveling at scenic designer Boris Aronson’s avant-garde multilevel plexiglass and chrome set and attacking its various urbanistic spaces with matched imagination in their movement direction, as well as melancholy-tinged playfulness that riffed on Furth’s book and Sondheim’s score.

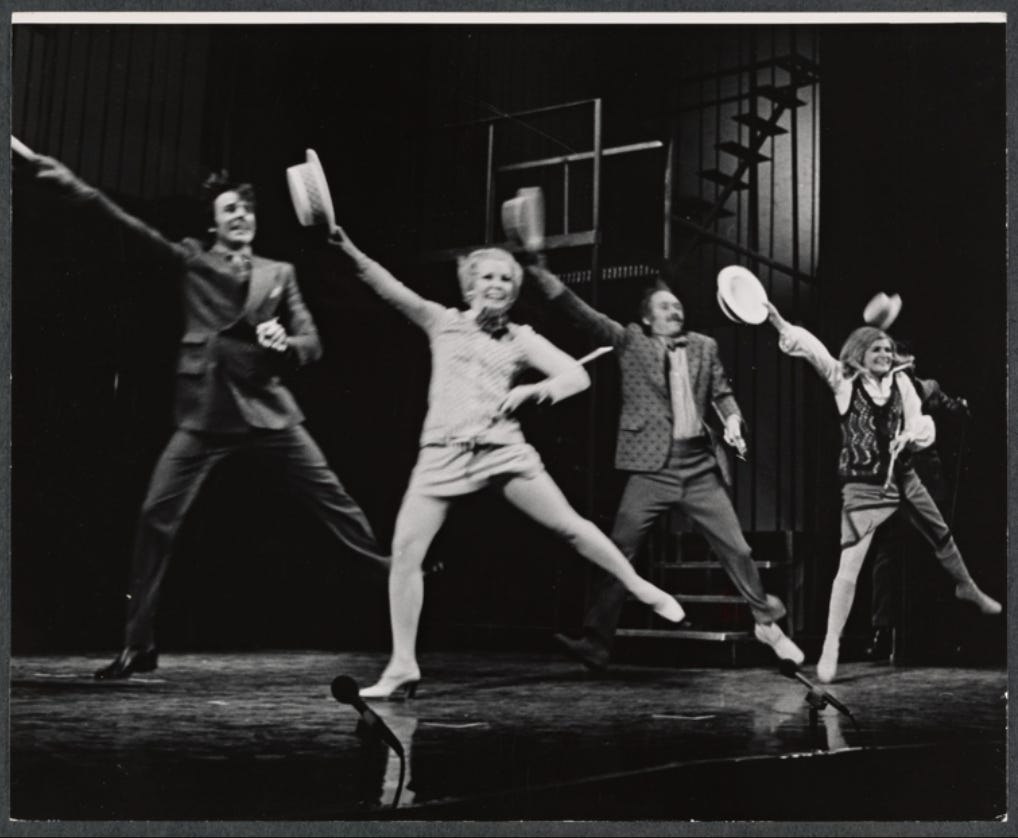

In Company, there is one production number that especially demonstrates Bennett and Avian’s ability to work within constraints and create something transcendent: the “Side By Side By Side” / “What Would We Do Without You?” moment that opens Act Two.

Sondheim explained: “We wanted to have a small cast.14 Hal [Prince]’s idea was to have them living on stage all the time, which didn’t work out. It was Michael’s idea to use them as a kind of P.T.A. group when it came to company numbers such as ‘Side by Side.’ They would be treated not only as people who were each other’s company, but they would be a company of semi-amateur singers and dancers.”15

In a 1979 interview with Svetlana McLee Grody and Dorothy Daniels Lister, Bennett recounted how he and Avian turned what many in their position would consider a drawback—a cast of performers with various levels of movement ability—into an asset on Company.

“We would only be as good as the worst person up there,” he noted, and added that the dances were the “kind of numbers [the actors] would do with overenthusiasm and doing practically nothing stepwise.” He elaborated: “That you see, is dealing with a problem and a cast that was already hired before we got involved. We had Barbara Barrie, Elaine Stritch, Donna McKechnie. It ranged from brilliant dancing to George Coe, who couldn’t walk. We literally taught him how to walk in the beginning. So it was, how do we solve that problem and still supply those production numbers, the feel of a big dance number?”

In the final section of the number, Bennett and Avian drew out the metaphor of the show—and underscored Bobby’s predicament in its climax—with simple, moony panache.

“The big moment of the number was when every couple did a tap break,” Bennett explained as he mimicked rhythmic tap steps. “Half of the couples did da, da da, da, da, and the other half did, duh da, shave and a haircut, ten cents. It then led to Bobby, the main character, who was alone, the only one who wasn’t a couple in the midst of all these couples. He did the first part of the tap break and there was silence at the other end. In other words, some things take two, to put it mundanely.”16

As Ted Chapin reflected in his 2003 book Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical Follies: “The audience wasn’t prepared for [that moment], yet it told us everything we needed to know about how single and alone that character was, especially as the rest of the company continued to dance cheerily on with their partners beside them while Bobby just stared at the empty spot on the stage.”17 (You can delight in director Lonny Price and choreographer Josh Rhodes’s homage to Bennett and Avian’s original staging in the 2011 New York Philharmonic gala concert production of Company here.)

Avian noted: “[Company] was staged wall-to-wall in terms of choreography. Some people assume that when they see a staged song that has three or four people in it, that it isn’t choreography. But you spend as much time and energy on staging that song as you would on a whole ballet, in fact more.”18

Have I Got a Girl For You

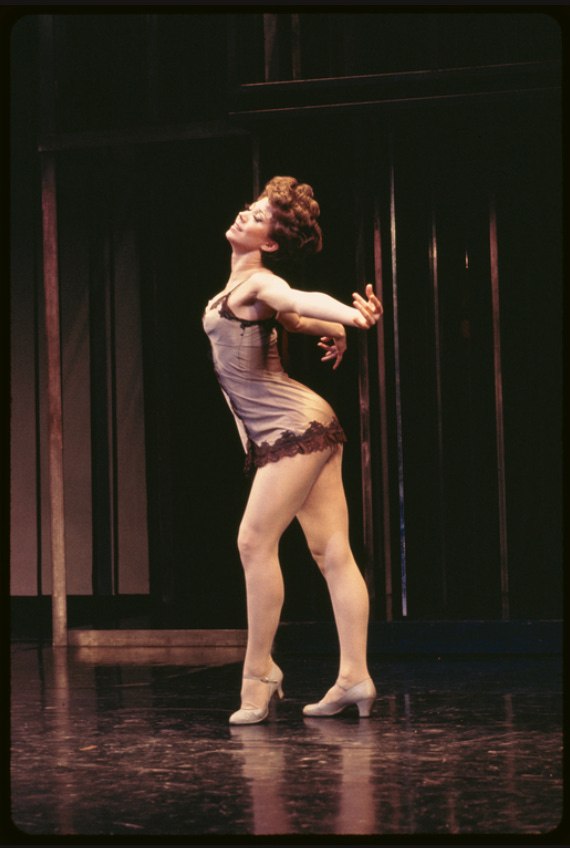

The only “pure dance” number in Company, “Tick-Tock”—an impressionistic piece that’s a pinch of Agnes de Mille, a dash of Joffrey Ballet’s sexy-radical Astarte—is a solo number originally developed by Bennett as a “rock ballet.” It functioned as an “artistically daring” showcase for McKechnie, the only performer with capital-D dance chops in the cast.19

The number “was intended to comment on Robert’s inability to commit to a relationship,” McKechnie wrote in her 2009 memoir. “The dance took place while Robert was having a one-night stand with a stewardess, played marvelously by Susan Browning.” She recalled that early in the Company rehearsal process, Bennett told her he wanted to create a piece that reflected the withdrawn loneliness someone feels when they’re in bed with someone but can only focus on their restless thoughts, symbolized by the tick-tocking of the clock.

“You know when you’re in bed with someone, and you’re making love, but you’re not really into it,” she remembered Bennett explaining his concept. “You hear the clock ticking and you’re more aware of that sound than you are of the person you’re with. So you really feel alone. Do you know what I mean?”20 In the moment, McKechnie told Bennett that she didn’t relate to what he was describing. In hindsight, however, the number further revealed not only Bennett’s keen understanding of the show’s overarching themes but also his own conflicted interior life. (That’s a different guest essay.)

“Tick-Tock” was almost cut by Prince during the show’s Boston tryouts until McKechnie boldly asserted her case for it to stay. The number survived—and thrived to the beat of David Shire’s incredible dance music arrangements—though because it was uniquely built on McKechnie, it is seldom performed in current productions of Company. (That said, you can see McKechnie thrillingly revisit it in the 1993 reunion concert production of Company here, plus Rhodes’s rendition of it here featuring Chrissie Whitehead in the aforementioned 2011 gala concert).

Notably, “Tick-Tock” served as foreshadowing for another psychological number that Bennett would develop for McKechnie five years later in A Chorus Line: prodigal chorus girl Cassie’s impassioned cri de cœur, “The Music and The Mirror.”

Company may have marked Bennett’s first true experience experimenting with non-linear narrative, but it proved a natural fit for how he innately approached his work as a choreographer and interpretive artist, regardless of whether a show’s structure was conventional or not.

“Because [Bennett] was very alive to his time, he was very aware that expressing things in a fragmented, non-linear way was of his time, and so that’s how he did it,” said Charles Willard, the company manager of the original production of Company on Broadway and on tour. “He didn’t intellectually reject doing an old-time, linear show. He just didn’t feel it that way, so it didn’t come out that way. But he never lost that kind of Irving Berlin sense of show business either.”21

Bennett and Avian’s next project with Prince and Sondheim was to feature a story that unfolded in an ostensibly “show business” setting, a literal theater—albeit a crumbling one on the brink of demolition.

No longer just choreographers for hire, this time Bennett and Avian would come in at the ground floor, working intimately with the rest of the creative team to meaningfully develop and mold the material. This new production would prove particularly significant in Bennett’s artistic evolution from a gifted choreographer to a multifaceted director capable of not only interpreting complex ideas but bringing them to their fullest expression.

“Hats off. Here they come, those beautiful girls…”

Natalie Guevara’s masterful survey of Michael Bennett’s contributions to the Prince-Sondheim canon will continue next month with an in-depth look at Follies. To be the first to read this, make sure to subscribe (free or paid) to The Sondheim Hub:

A Chorus Line and the Musicals of Michael Bennett by Ken Mandelbaum, “Epilogue: Remembering The Man,” page 275 (St. Martin’s Press, January 1989)

Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created Sunday in the Park with George by James Lapine, “The Booth Theatre: Previews,” pages 221-222 (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, August 2021)

This clip is mislabeled on YouTube as July 1987. In fact, the private memorial for Michael Bennett was held at the Shubert Theatre on September 29, 1987, as his circle needed time following his death to arrange a celebration befitting Bennett’s theatrical prowess. “How can you expect hundreds of people to come to the Shubert Theatre in memory and tribute to Michael Bennett, and not ask Michael what he wanted us to do?” explained Breglio during his section. In addition to Sondheim, there were tributes read by Joe Papp, Donna McKechnie, Bennett’s brother Frank DiFilia, and his trusted creative team, plus performances from the current casts of A Chorus Line and Dreamgirls as well as A Chorus Line composer Marvin Hamlisch and songwriter Jimmy Webb, with whom Bennett spent the better part of the 1980s developing two provocative musicals (Scandal, The Children’s Crusade) that sadly never made it to the stage.

A Chorus Line and the Musicals of Michael Bennett by Ken Mandelbaum, “Prologue: No Show Runs Forever,” page 5 (St. Martin’s Press, January 1989)

Time Steps: My Musical Comedy Life by Donna McKechnie, “Company,” page 88 (Simon & Schuster, November 2009)

A Chorus Line and the Musicals of Michael Bennett by Ken Mandelbaum, “Part Two: Enter Michael Bennett—The Choreographer: Four Flops, One Hit,” page 34 (St. Martin’s Press, January 1989)

Conversations with Choreographers by Svetlana McLee Grody and Dorothy Daniels Lister, “Thommie Walsh,” page 186 (interview with Walsh originally conducted in fall 1994; interview included in book published by Heinemann Drama in June 1996)

Conversations with Choreographers by Svetlana McLee Grody and Dorothy Daniels Lister, “Michael Bennett and Bob Avian,” page 114 (interview with Bennett and Avian originally conducted in spring 1979; interview included in book published by Heinemann Drama in June 1996)

Conversations with Choreographers by Svetlana McLee Grody and Dorothy Daniels Lister, “Michael Bennett and Bob Avian,” page 114 (interview with Bennett and Avian originally conducted in spring 1979; interview included in book published by Heinemann Drama in June 1996)

Making Broadway Dance by Liza Gennaro, “Broadway Dance Post de Mille/Robbins: Michael Bennett,” page 175 (Oxford University Press, December 2021)

Conversations with Choreographers by Svetlana McLee Grody and Dorothy Daniels Lister, “Michael Bennett and Bob Avian,” page 109 (interview with Bennett and Avian originally conducted in spring 1979; interview included in book published by Heinemann Drama in June 1996)

Making Broadway Dance by Liza Gennaro, “Broadway Dance Post de Mille/Robbins,” page 150 (Oxford University Press, December 2021)

Making Broadway Dance by Liza Gennaro, “Broadway Dance Post de Mille/Robbins: Michael Bennett,” page 171 (interview with Lee originally conducted in 2019; interview included in book published by Oxford University Press, December 2021)

On page 142 of her book, Gennaro notes how choreographers—and indeed, all creative teams making new work in the late ‘60s and ‘70s—had to adapt to changes in the musical form, which spanned from changing public tastes to budgetary restraints on cast sizes, “disadvantages” that concept musicals took full advantage of, if not altogether lionized, as they rose in prominence throughout the era.

A Chorus Line and the Musicals of Michael Bennett by Ken Mandelbaum, “Part Two: Enter Michael Bennett—New Concepts: Company and the Concept Musical,” page 59 (St. Martin’s Press, January 1989)

Conversations with Choreographers by Svetlana McLee Grody and Dorothy Daniels Lister, “Michael Bennett and Bob Avian,” page 98 (interview with Bennett and Avian originally conducted in spring 1979; interview included in book published by Heinemann Drama in June 1996)

Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical Follies by Ted Chapin, “Introduction,” page xxvi (Alfred A. Knopf, October 2003)

Conversations with Choreographers by Svetlana McLee Grody and Dorothy Daniels Lister, “Michael Bennett and Bob Avian,” pages 103-104 (interview with Bennett and Avian originally conducted in spring 1979; interview included in book published by Heinemann Drama in June 1996)

Time Steps: My Musical Comedy Life by Donna McKechnie, “Company,” page 84 (Simon & Schuster, November 2009)

Time Steps: My Musical Comedy Life by Donna McKechnie, “Company,” pages 84-85 (Simon & Schuster, November 2009)

A Chorus Line and the Musicals of Michael Bennett by Ken Mandelbaum, “Part Two: Enter Michael Bennett—New Concepts: Company and the Concept Musical,” page 61 (St. Martin’s Press, January 1989)

A wonderful read!

Your passion for Michael Bennett’s legacy shines through. I can’t wait for Part Two and your take on Follies.