In Sunday in the Park with George, we meet a fictionalized version of Georges Seurat—intense, obsessive, married to his art at the expense of all else. “I am not hiding behind my canvas. I am living in it,” he says. But how might we best get a sense of the living, breathing Seurat? And how might knowledge of the real man inform our understanding of the character we’ve come to know so well?

Born in Paris in 1859 to a comfortable middle-class family, Georges Seurat showed artistic promise from an early age. Unlike the struggling artists of the popular imagination, he did not face extreme financial hardship—his father, a customs official, had accumulated enough wealth to offer some financial stability. While not entirely free from economic concerns, this relative security allowed Seurat a degree of independence in pursuing his artistic vision. It enabled him to work in relative isolation, developing his theories and techniques without the immediate pressures of commercial success.

“I want to make modern people, in their essential traits, move about as they do on those friezes, and place them on canvases organized by harmonies,” Seurat once declared. This seemingly simple statement encapsulates much of what made him unique—the desire to combine classical composition with thoroughly modern subjects, all unified by his revolutionary approach to color and light.

His contemporary, the critic Félix Fénéon, who coined the term “Neo-Impressionism” to describe Seurat’s technique, wrote of first encountering A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte: “The eye experiences a feeling of illumination... The atmosphere is transparent and singularly vibrant.” This vibrance, of course, was no accident.

Seurat’s groundbreaking approach to color and light didn’t emerge fully formed. Before La Grande Jatte, he had been experimenting with these ideas in works like Bathers at Asnières (1884). The painter Charles Angrand recalled visiting Seurat’s studio during this period: “He showed me studies for the Bathers – small panels covered with tiny, regular strokes, crosshatched in every direction. Already one could see his tendency toward systematic division of tone.” The art critic Gustave Kahn would later write that these early experiments revealed “a mind perpetually in search of new methods of expression.”

Seurat’s personality remains somewhat elusive in historical records, but those who knew him consistently describe a man of extraordinary focus and intellectual rigor. Paul Signac, his closest artistic collaborator, described him as “methodical, serious, reserved, severe.” Charles Angrand noted that he was “very correct, very quiet, but obstinate – a resigned revolutionary.”

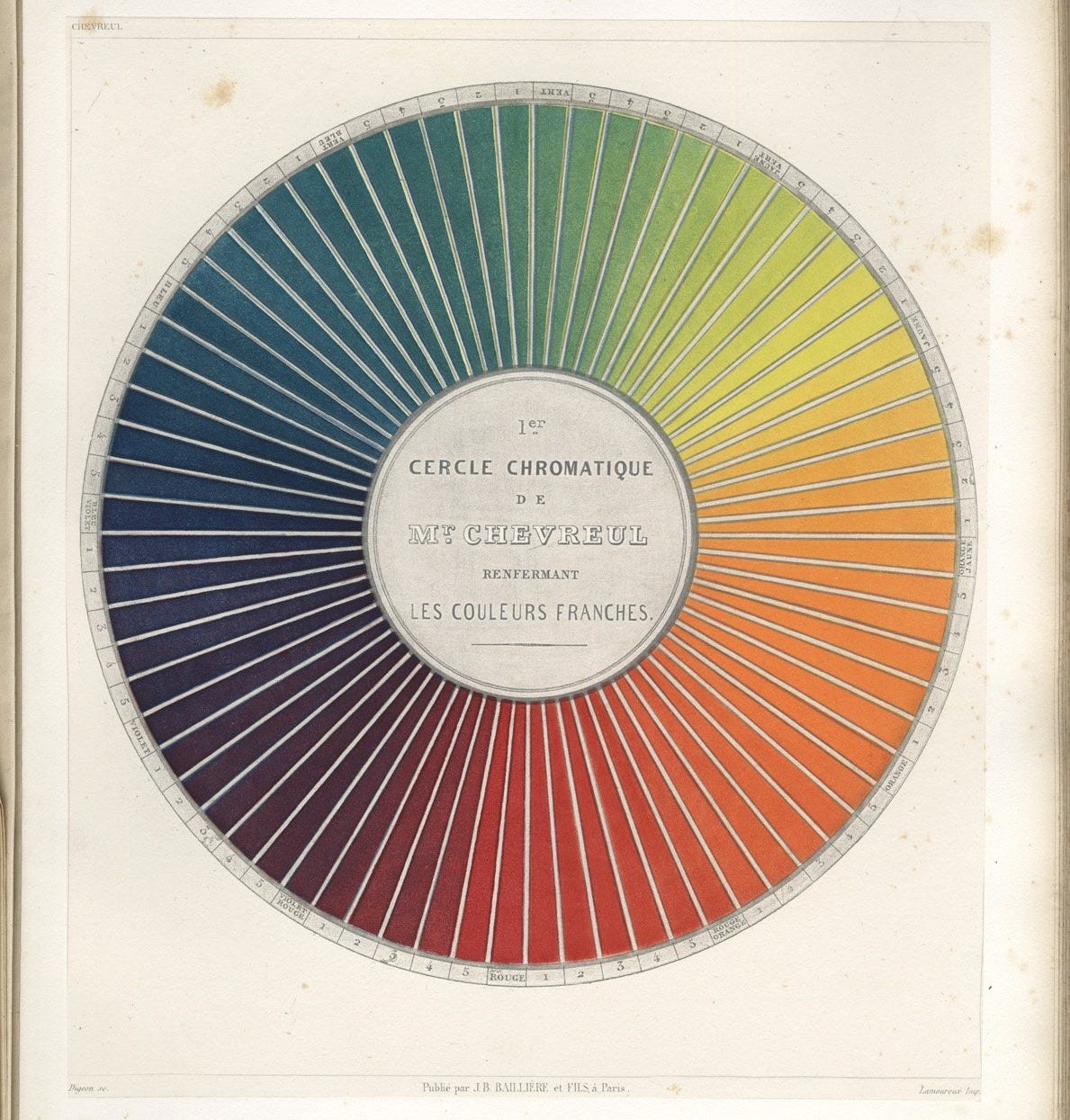

This “resigned revolutionary” approach extended to every aspect of his work. Unlike the Impressionists who preceded him, Seurat approached painting with scientific precision. He studied color theory extensively, particularly the works of Michel Eugène Chevreul (especially his 1839 treatise On the Law of Simultaneous Contrast of Colors, with its famous color wheels and contrast studies) and Ogden Rood, whose 1879 book Modern Chromatics included groundbreaking illustrations of color perception and optical mixing. Seurat would often tell his fellow artists that “they worked by instinct whereas I worked by mathematics.”

Seurat’s scientific approach extended beyond color theory. He was fascinated by the emerging field of optical psychology, particularly the work of Charles Henry on the emotional effects of lines and colors. Henry wrote that Seurat “asked me to explain to him the essential elements of my theory of direction and deduction... He listened with that calm attention that characterized him, saying little, but every now and then making a brief observation that showed how deeply he had understood.”

Yet there was nothing cold or mechanical about his work. The critic Jules Christophe observed: “Some say that Seurat’s method kills all life, all spontaneity.” We might note here that the man who declares in Sunday in the Park with George that Seurat’s work has “no life” is also named Jules. The real Jules, though, continues, “But look at his drawings – such sensitivity, such delicacy!” Indeed, Seurat’s drawings reveal a softer side to his artistry, one that belies the common perception of him as purely analytical.

The real Seurat was intensely private about his personal life—so private that when he died at the tragically young age of 31, many of his closest associates were surprised to learn he had been living with a young woman, Madeleine Knobloch, and had a son. This secrecy wasn’t born of shame, but rather from a deep-seated belief that his private life should remain separate from his art. Here, Sondheim and Lapine’s portrayal rings particularly true—their George’s obsessive privacy, his reluctance to let anyone, even Dot, truly know him, reflects what we know of the historical figure.

Seurat’s sister-in-law’s recollections provide one of the few glimpses into his domestic life: “He would work from morning until night, stopping only to eat... He spoke little, but when he did speak about art, his eyes would light up with an inner fire.”

This dedication to his work was noted by many who knew him. The painter Albert Dubois-Pillet recalled: “I have never known anyone who worked with such concentration. He would stand before his canvas for hours, studying it as if it were a mathematical problem to be solved.” Yet this mathematical approach produced deeply human results. As the poet Gustave Kahn observed: “Despite all the scientific precision, there was something profoundly moving about watching him work. It was like witnessing the birth of a new way of seeing.”

What’s particularly fascinating about Seurat is how his theoretical approach to art coexisted with genuine emotion and social consciousness. While he’s often portrayed as being solely concerned with technique, his choice of subjects reveals a keen observer of modern life. The people in his paintings—from the circus performers to the Sunday strollers—represent a cross-section of Parisian society.

Art historian Robert L. Herbert noted that Seurat’s work contained “a vision of modern life that was both ordered and mysterious.” This duality—between order and mystery, science and emotion, tradition and innovation—seems to have been at the core of Seurat’s character.

This duality was particularly evident in his later works, such as Le Chahut and The Circus. The art critic Arsène Alexandre wrote in 1891: “In these latest paintings, we see how Seurat has managed to combine his rigorous technique with an almost magical sense of movement and life. The dancers in Le Chahut seem to float in space, yet every position, every gesture, has been calculated with extraordinary precision.”

The real Seurat emerges as someone more complex than either the romantic stereotype of the artist or the cold technician. He was a man who believed that art could be approached with scientific rigor without losing its soul. Vincent van Gogh, after seeing Seurat’s work, wrote to his brother Theo: “Seurat’s technique is a system, but what a system! And what results!”

The painter Henri-Edmond Cross, who knew Seurat well in his final years, provides us with a particularly poignant recollection:

He was always pushing forward, always seeking new solutions. In our last conversation, just weeks before his death, he spoke of new ideas he wanted to explore – ways to make his dots of color create even more vibrant effects. He never saw his technique as finished or perfect; it was always evolving.

Seurat’s early death in 1891 left many questions unanswered. We’ll never know how his art might have evolved, whether he would have pushed his technique further or moved in new directions. But what we do know suggests a man of fascinating contradictions: methodical yet innovative, reserved yet revolutionary, scientific yet deeply artistic.

The Seurat of Sunday in the Park with George captures something true about the artist’s dedication to his work, but the real man was neither as emotionally stunted as his fictional counterpart nor as purely cerebral as some art historians have portrayed him. Where Sunday’s George seems trapped between art and life, unable to bridge the gap, the historical Seurat appears to have found his own peculiar balance. He was someone who sought to unite the rational and the emotional, the classical and the modern, the scientific and the artistic. His relative isolation seems to be a choice made in service of his vision—not, as the musical suggests, an inevitable consequence of his character.

As we look back at Seurat’s life and work, we see someone who changed art history not through dramatic gestures or revolutionary manifestos, but through quiet, determined innovation. He showed that new ways of seeing and creating were possible, that tradition could be honored while being thoroughly transformed, and that science and art could work together to create something entirely new.

The Belgian poet Émile Verhaeren, writing in 1891, observed:

What Seurat achieved in his brief life was nothing less than a revolution in how we see color and light. He showed us that the world is made not of solid, unchanging hues, but of countless points of color, eternally vibrating, eternally alive.

And shortly after Seurat’s death, Danish-French painter Camille Pissarro wrote the following in a letter to his son Lucien:

Yesterday I went to Seurat’s funeral. I saw [Paul] Signac who was deeply moved by this great misfortune. I believe you are right, pointillism is finished, but I think it will have consequences which later on will be of the utmost importance for art. Seurat really added something.

“Seurat really added something.” What more can any of us wish for?

In the end, the real Georges Seurat stands as a reminder that great artists don’t always fit our preconceptions. Sometimes they work with mathematical precision rather than wild abandon, speak through careful theory rather than passionate declarations, and change the world not with grand gestures but with flecks of light.

Further Reading

If you’re in the mood for more Sunday-related reading, try these essays on “Beautiful” and “It’s Hot Up Here,” published last year:

It's Hot Up Here

Precisely a hundred years elapse between the two acts of Sunday in the Park with George, but when the second curtain rises it seems as though not a moment has passed. Those on stage appear exactly as we last saw them: a tableau, frozen in time. Seurat’s painting is complete, its subjects fixed forever in their various poses—much to their chagrin. The op…

You mention Angrand here. At a recent Sotheby's pre-auction exhibition I stumbled onto an astonishingly Seurat-like painting, Coin du Parc Monceau, which turned out to be by Angrand. Lit by one spot above it, the pointillistic image of a park with one human walking in the distance seemed to reach out in a 3-D manner into the viewer's face! Photos of the painting don't have that effect, unfortunately. But I thought it was worth sharing here.